Simon Quilty

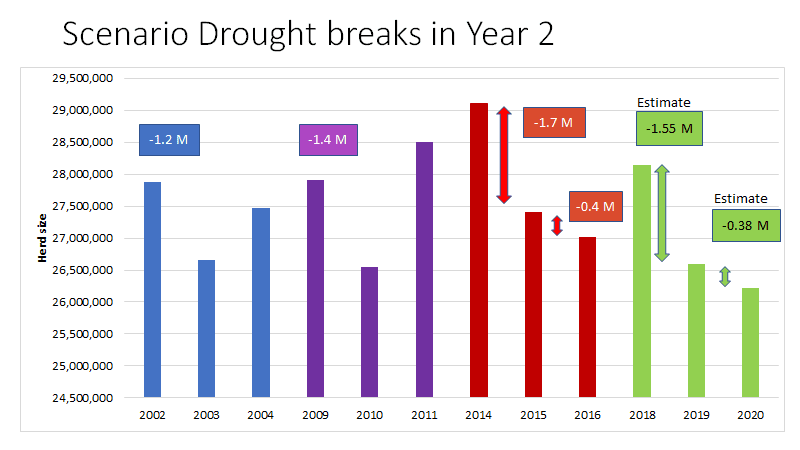

In this comprehensive study, independent analyst Simon Quilty raises the question of whether the 2018 seasonal conditions represent a ‘drought on steroids’ and estimates that herd liquidation based on a two-year drought scenario could strip two million cattle out of the Australian production system.

MAKING announcements about emergency financial support for farmers last week, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull described this year’s drought as “one of the worst of the past century.”

In addition, a report was released yesterday by the National Academy of Sciences based in the US which referred to the ‘hothouse’ climate, whereby average temperatures could reach 5c higher than pre-industrial temperatures, while discussing the consequences of this phenomenon.

Looking at Australia’s April rainfall and temperature measurements would suggest we are well on our way to this situation.

It should be noted that when assessing drought in this report, I refer to the Australia-wide drought beginning in March this year, but in reality QLD moved into drought last year in September/October (and is some regions even earlier); VIC at the start of the 2018; and the NSW drought started in March/April this year (once again some NSW regions were much earlier). For ease of writing I have referred to the March commencement of the Australia-wide drought, and not when individual states or regions succumbed.

Is this now a drought on ‘steroids’, as described by one farmer this week?

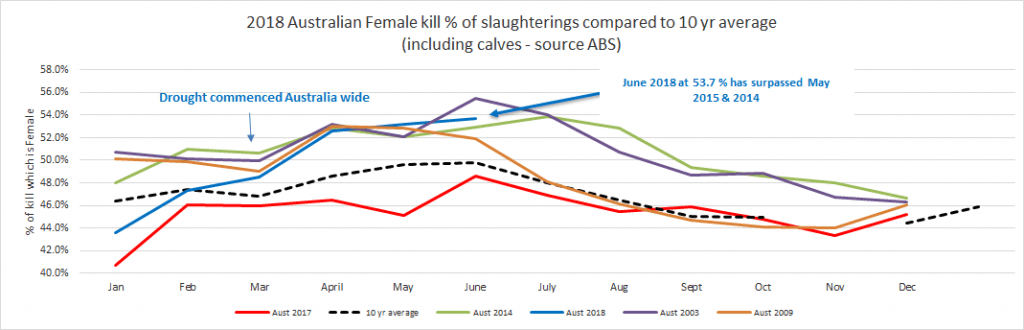

In terms of its ferocity and impact, in such a short time frame, it can be argued that that is the case, and the case is supported by yesterday’s ABS figures that give us the best measure, I believe, of how ferocious this drought has been to Australia’s beef herd and sheep flock.

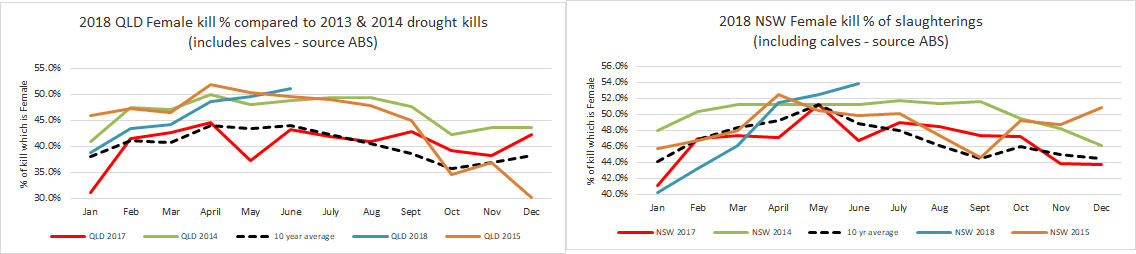

Summarising the ABS data, the drought has intensified in the last four weeks with the Australian female kill (as a proportion of overall slaughter) moving higher to 53.7 percent Australia-wide, with NSW (53.8pc) and QLD (51pc) being the most severely impacted states. Victoria seems to have moderated with less females slaughtered (falling from 64.9pc in April to 60.1pc in June – the annual dairy cull inflates these figures)

What appears to be so irregular about this drought is the short period of time taken for the severity to ramped-up, reaching a 53.7pc national female slaughter very quickly. In previous droughts this would normally take 12-18 months to get to the same point, while in 2018 it has taken only four months. The key difference seems to be the higher temperatures that have ‘burned off pastures’ and caused crops to fail. Rainfall deficiency is also crucial, but the weather records have been broken more on recent temperatures, than lack of rainfall.

Current intensity – April was a super drying-out month

A failed spring and no autumn break is what has been the precursor to the drought in NSW, VIC and Southern QLD, with many areas getting very little rain along the Eastern Seaboard.

As one nutrition expert explained to me recently, ‘It stole winter from us’, meaning that there was no moisture reserve to top-up and any pastures which were burnt-off earlier, leaving nothing for late autumn to carry into winter. This has been particularly evident north of the Murray River.

The winter in many areas has seen extremes in frost and warm days which has had the added effect of preventing pasture growth and impacting cattle conditions.

The drought, Australia wide began in March and it was in April that Australia experienced some extreme weather conditions that knocked the stuffing out of pastures which were already mediocre at best. And the real damage was done to what little feed was available and ramping up the impact of the dry to seeming like it was on ‘steroids’.

April was recorded as the second-warmest on record for mean temperature and more importantly it was the highest on record for mean maximum temperature being 3.17 °C above the average. April rainfall for Southern Australia was the third-lowest on record and the eighth-driest on record Australia wide.

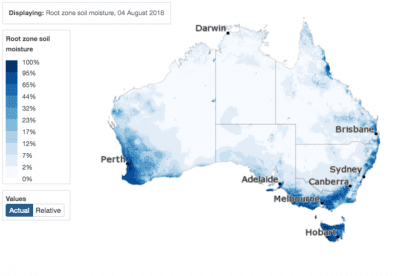

The best analogy to describe what happened was given to me by a soil scientist who said, “You need to look at the sub-soil as a layer of sponges – the first two layers being the root zone and the third and thickest sponge is the deep soil moisture layer.”

It would seem that in April when temperatures were at record-highs, it quickly evaporated the moisture from the top layer sponges and dried them out in 4-6 weeks, that in previous droughts had taken 12 months to do the same job. The impact on pastures and crops in those regions have been dramatic.

The ‘top layer’ sponges are now bone dry in most parts of Australia. This is not to say that all regions are in the same boat, or are experiencing the same severity. Areas like western Victoria are better-off, but you can count them on one hand.

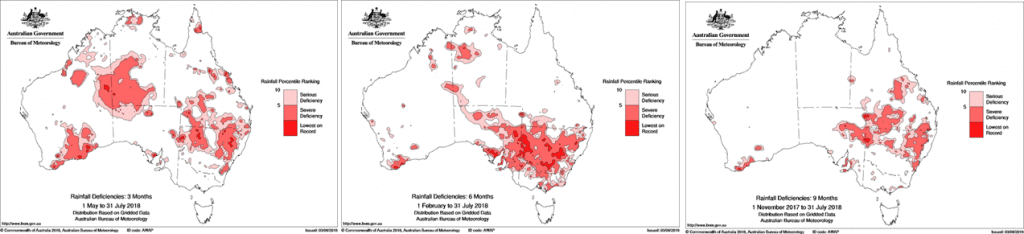

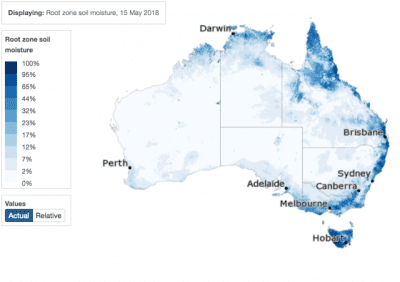

The rainfall deficiency maps below highlight when the drying-out of the top layer sponges (root zone) occurred, with SE QLD and central QLD occurring nine months ago. But the intensity for NSW was in April, which is best highlighted in the second graph (six months). When the high temperatures and lack of moisture are overlaid, it gives a lethal combination – with the weather momentum being maintained in May, June and July when rainfall remained low and monthly average and maximum temperatures remained at near-record levels.

It has left the entire industry caught-short for feed, that they were hoping was going to give an extra 2-3 months of feed in the system.

Rainfall deficiency – 3, 6, 9 months

Subsoil moisture – May and August

Click on images for a larger view

What has brought forward the high rate of female kill unlike previous droughts?

Ironically, the high rate of female kill that has come so early in this drought, I think, can be partly explained by the strength of global meat markets and how the drought has unfolded in the last 12 months since it began in QLD last year, before spreading south.

Feed costs continue to rise and lighter feeder steers values continue to fall

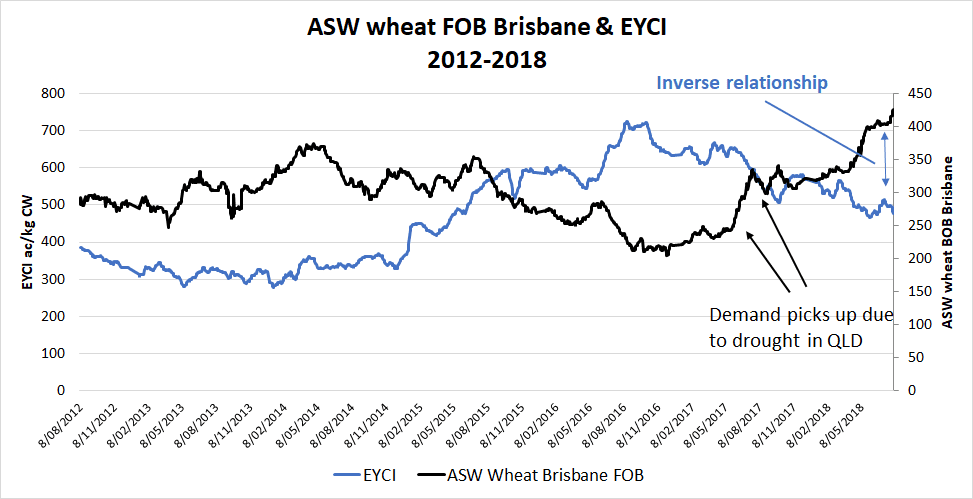

If you cast your mind back to last year, QLD was the first to experience drought in August/September. While the intensity was not as great as it is now, it still required many to supplementary feed or seek other finishing solutions. The feedlot sector had seen + one million head on feed, and this saw the demand from QLD for different feed types increase dramatically during the third and fourth quarter last year (see below). This effectively removed large volumes of ‘surplus’ feed out of southern Australia into the northern NSW and QLD regions.

This was driven by demand for heavier feeder steers and slaughter ready cattle because global beef prices have been strong. So even at these higher grain/feed prices, the market was willing to pay these high input costs to finish cattle off as global prices were strong.

Southern calving versus northern calving in Australia

The production systems of northern and southern Australia are different, with southern Australia dominated by autumn calving and northern NSW and QLD dominated by spring/summer calving (this is a generalisation and may not hold to all operations).

The problem caused by such a hot April, was that it resulted in southern pastures prematurely drying out forcing many southern farmers to make the hard decision about carrying cows – and when looking for supplementary feed it was too expensive or not to be found.

Effectively ‘plan B’ had been removed which in the past would have seen some autumn growth and feed reserves enabling producers to carry livestock through winter, but the lack of excess feed forced cattle (in particular, cows) to come to market early. This was seen in Victorian female kills in April that reached 65pc of total slaughterings – almost equal to the peak of the last three droughts – only as stated earlier, this peak occurred for Victoria 12-18 months into in each drought, not four months after it commenced.

The same hard decision will be made soon in spring/summer calving operations (northern NSW and QLD) whereby spring calves are due, and whether to carry the cows or send them to market as soon as the calves are weaned. Some operators have decided to sell as pregnant cows, given they have no feed for either the mother and/or the calf – some hard decisions.

So a second wave of cows to be sold is not far off, as more northerly farmers make similar hard decisions as there southern counterparts had to make earlier.

The lack of biomass

The lack of biomass (roughage) has further acerbated the problem, and for many operations is just as critical as quality protein feed. The biomass ensures consistent and reliable diets and many multi-grain diets require long fibre biomass for digestion. Roughage has proven to be even harder to find at times than grain, with rice straw at the moment one of the few (poor) alternatives.

As a nutritional expert explained to me recently, “To produce consistent and reliable diets, you need long fibre. In previous droughts, it’s been the reverse – long fibre has been more abundant and protein meal has been scarcer. You can still find protein meal like lupins ($500/tonne), peas ($400/tonne) and canola meal, but unfortunately it’s at record or near record prices, and long fibre is even harder to find.”

Prospects for another super drying-out month soon

The occurrence of another super drying-out month like April is what has many farmers concerned – this is impossible to predict, and the consequences can be devastating, as we saw in April. The two key periods of pasture growth being spring and autumn, and any excess heat spell will see pastures deteriorate quickly. The BOM in its most recent forecasts has predicted days and nights likely to be warmer than average during August to October for most of Australia, with August days very likely to be warmer than average.

The most concerning month for another super-drying month would be October, as most producers in southern Australia are looking to finish cattle off in September-November period and a rapid October deterioration of pastures would result in animals being unfinished.

Length of previous droughts

What is concerning is that we have got to the final stages of a regular drought in terms of liquidation far too quickly. That would typically occur in the back-end of a two-year drought, and instead this year, we have arrived there within four months.

It is important not to generalise too much about droughts and regions that are in drought or not, as so often it shows that the start and finish of any drought can be very patchy. Some areas can experience the dry conditions long before others, and the same occurs at the tail-end of droughts where the rain often comes in patches and can be very regionalised, rather than delivering a clearly-defined start and finish. So the following estimates should be seen as a ‘broad-brush’ approach.

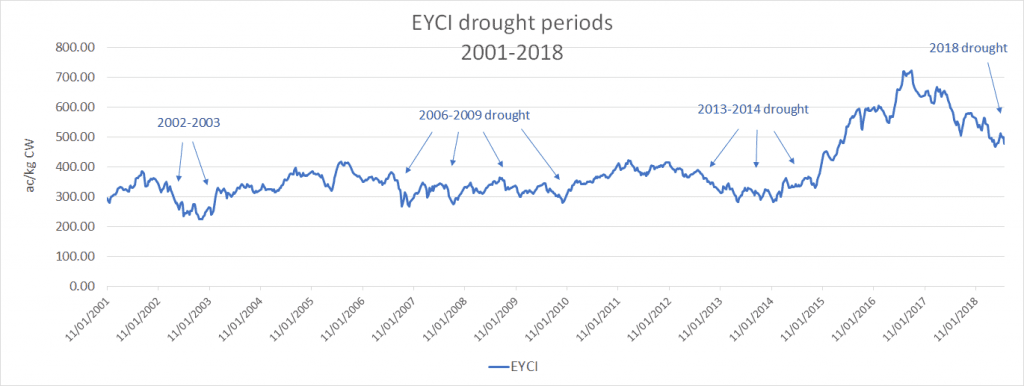

The following is the key previous drought periods and highlights the period of time they lasted:

- 2003-2004 drought lasted 16 months

- 2006-2009 drought lasted 36 months

- 2013-2015 drought lasted 24 months

Based on recent history, this gives an average of 25 months – as I stated the concern is that we are only four months into this drought in southern parts of the continent.

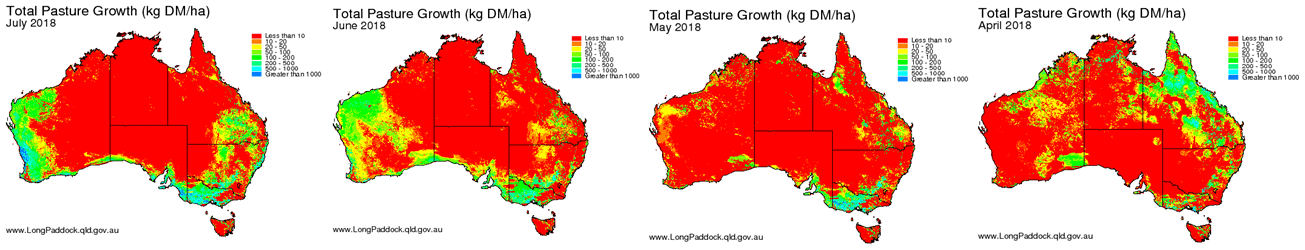

The last four months of rainfall shows below how patchy conditions are still and also that in many areas there is very little to no subsoil moisture and that these pasture maps can be deceiving.

Fertility/joining rates are likely to decline

One of the consequences of severe droughts is fertility rates fall for both sheep and cattle. It can be expected that in regions that normally enjoy 90+pc fertility rates with cattle and 130-150pc with sheep, may expect joining successes of only 50-60pc, I am told.

Drought conditions can impact fertility rates and calving in several ways:

- Cows can become infertile due to poor conditions and do not conceive due to stress.

- The pregnant cow being mal-nutritioned in the critical 60 days prior to calving can result in weak calves or still born calves.

- Cows’ energy requirements are substantially higher during pregnancy, and in drought may use their own body fat as a source of energy. But this is often unsustainable for extended periods and can result in pregnancy toxaemia or ketosis which in turn leads to liver failure if left untreated.

- Pregnant cows in drought can produce inadequate quality and quantity of colostrum – colostrum contains antibodies that protect the newborn calf or lamb against disease.

- Calves in drought can struggle to get to an adequate weaning weight and can see growth problems post-weaning with muscle development slow and early fattening.

- The ability to maintain cows after calving is difficult as the nutritional needs during lactation are high and if not maintained can see cows deteriorate quickly and in some instances unable to be transported due to their weak condition.

- The next-season pregnancy can be also impacted even if the drought has broken due to joining weights being too low below 300kg or poor body condition – this is particularly evident in first calf cows.

- Equally the performance of bulls during drought can be severely impacted due to stress resulting in low joining rates.

It is not surprising that when looking at herd liquidation that it occurs at an accelerated rate due to not only the high percentage of females/breeders being killed and removed from the herd, but also that remaining cows are reproducing at a significantly lower rates (perhaps 50-60pc), with no guarantee that the offspring will survive. This compounds problems, and explains how herds can fall so rapidly in a short period of time.

Drought impact on Australian production and global markets

MLA last week revised its production and shipping estimates for Australia this calendar year, based on current drought conditions, with production up 7pc on last year, and total exports up 10pc. I have used these estimates below.

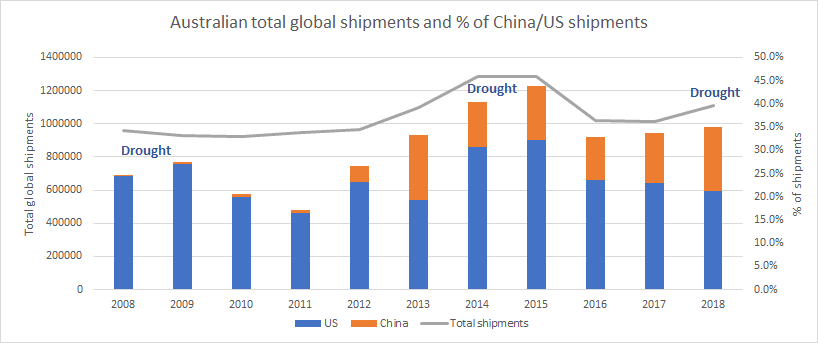

The impact of this drought on global markets has not been as significant as previous droughts, with July export figures showing shipments to the US still at only 22pc of total global exports. In the past, droughts have meant lean meat produced in abundance, which has tended to be directed to the US as grinding meat. As a result, exports to the US often rose to well above 30pc of global shipments, as in the past they were few alternatives to sell lean meat.

But today, China is playing a critical role in absorbing this product.

The graph below shows the growing importance of China as a lean meat market, even during drought, along with the US. Back in the 2006-2009 drought, China as a market was almost non-existent for Australia, but since then, it has increased its market share and in 2018 US shipments look to be falling percentage-wise, even though Australia is in drought. China’s demand has reversed this past trend of the US being one of the only destinations for the abundance of lean beef that tends to be produced.

Herd liquidation continues

The ABS figures released yesterday highlight that the liquidation process has intensified with QLD and NSW droughts in particular becoming more serious, with the largest and second largest Australian beef producing states moving to a higher level of liquidation of 51pc and 53.8pc respectively.

Based on the factors outlined above and the intensity of this drought, the impact on fertility rates and should feed costs remain at near record levels, my estimates below of a 1.55 million head liquidation in the first 12 months, followed by a 380,000 head reduction in the second year of a drought might seem to be conservative. But I believe that given that we have started from a low herd base of 28.3 million head, that these estimates may still occur.

It is still very early days, and I am hoping that we do not enter into a second year of drought, as the time period to recover and the ability to recover will be very difficult.

Drought inevitably compounds problems, whether it is the cost of feed, fertility rates, joinings or simply cash flow, and the ability to keep feeding sheep or cattle that are costly to maintain and if they remain light, continue to fall in value. The failure of a spring and autumn break and then the intensity of extreme warm temperatures in April has brought forward the liquidation process that I believe is unprecedented.

My views on this October being the low in the Australian price cattle cycle (referenced in our earlier reports) has not changed, with cattle prices, I believe, either improving or moving sideways with or without the continuation of drought. I do not see much further downside in pricing after October.

The only consolation to these extreme drought conditions is that when the drought breaks the rebound in cattle pricing will be enormous, and as discussed in earlier reports, I think will be sustained for an extended period.

The challenge for many is keeping the herd intact and surviving to hopefully enjoy the benefits of strong global beef prices in future.

Excellent report. I would point out that significant parts of western Queensland have been partially or completely destocked since 2015, and will remain so.

Excellent summary. hopefully, some media will read this and begin to concentrate on the future rather than just trying to capture photos of tears.