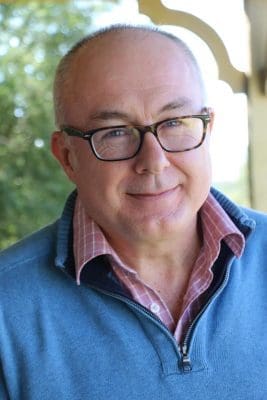

Simon Quilty

Independent meat and livestock industry analyst Simon Quilty ponders the beef industry’s Cattle Transaction Levy, and whether there is a better way to raise industry funds. It’s a subject he has intimate knowledge of, having worked on the topic for the VFF Pastoral Group back in the levy’s formative years in the 1980s.

I RECENTLY wrote several papers on Australia’s competitiveness globally in beef exports compared to our three largest competitors, the US, Brazil and India in key export markets.

One of the important takeaway messages from readers was Australia’s need to focus on niche marketing and playing to our strengths as an export country. One upcoming challenge is that when the drought breaks, Australia’s beef production and exports will fall dramatically, and with that will come diminishing market share in these key markets.

A consequence of that will be a dramatic fall in the available promotional and research dollars at the industry’s disposal, at a time when it could be argued that it is needed most.

There is a strong belief amongst some Beef Central readers that a more equitable cattle levy system is needed, that better reflects the financial difficulty being experienced by farmers during drought times, and when better seasonal conditions and higher cattle prices occur, allows farmers to pay a higher levy when they can afford to do so.

It is with this in mind that I would like to put forward some ideas around levy structures that I believe address these concerns and potentially gives a strategic advantage to Australia when industry funds are needed most.

It is with this in mind that I would like to put forward some ideas around levy structures that I believe address these concerns and potentially gives a strategic advantage to Australia when industry funds are needed most.

Change from a flat rate levy ($5 per head, per transaction, on all adult and grower cattle*) to an ad valorem (percentage of value) based system.

I believe that if the current flat rate of $5 per animal transaction levy was changed to an ad valorem or percentage based collection system – say 0.5pc of sale proceeds – it would ensure that during drought when prices are low, that farmers pay a levy that would be close to half the current $5/head, and more in line with what they can afford at the time.

And when times are good and cattle prices are higher, farmers would pay a higher levy of greater than $5, when they can afford to do so. In other words, introducing an equitable system that enables farmers to pay a ‘fair’ levy price that is more attune to their own financial circumstances.

The precedent already exists in the sheepmeat sector, and other agricultural industries where a percentage based levy system exists.

I believe though that a cap of $8/head would be required on the transactions to ensure that funds are kept in check, and that those livestock participants at the higher end of the marketing/value chain do not end up with a disproportionate portion of the levy to pay. This would be applicable in particular to Wagyu, stud stock and heavy bullocks producers, whose animal value tends to be much greater than the traditional breeds and grower cattle. Currently a bull producer selling bulls worth $8000 or $10,000 each pays the same levy as a weaner steer producer.

Looking back at the cattle transaction levy history

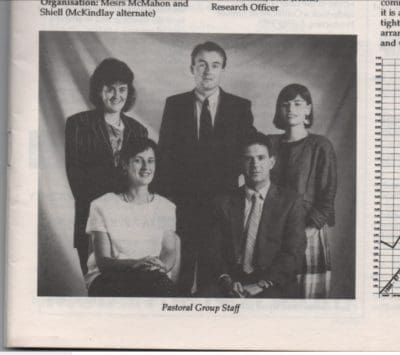

First, a bit of history. My first job in the Australian meat and livestock sector was with the Victorian Farmers Federation, where I worked from 1987-1990 as a research officer for the VFF Pastoral Group.

During my VFF tenure I was intimately involved with the decision by Cattle Council of Australia to change the collection method from the old slaughter levy to a transaction levy. The Australian Meat & Livestock Industry Policy Council (AMLIPC) employed Doug McKay as a consultant at the time who was the main architect of the change in 1988, and I was fortunate enough to work alongside Doug, assisting him in the research that ultimately led to the adoption of the transaction levy as we know it today.

Simon Quilty with VFF Pastoral Group staff, circa 1988. Kevin Shiell front right.

One of the principal beliefs by the VFF Pastoral Group (and Cattle Council of Australia) at the time of adopting the transaction levy was that ‘all industry participants should be seen to be contributing to the industry levy.’

Prior to this, collection of levies occurred at the meatworks only, and meat processors felt they were the only ones paying the industry bill. Today all livestock supply chain participants pay including breeders, backgrounders, fatteners, lotfeeders and processors.

In the 1989 VFF annual report it stated, “It was felt that with producers being clearly identified as paying the levy on their account sale, they could demand greater accountability from AMLC and AMLRDC in their activities, which would be good for industry.”

AMLC and the separate R&D body, AMLRDC, today exist under the one umbrella known as MLA. But this sentiment of wanting ‘greater accountability’ has not changed from farmers and all other levy payers.

At the time of introducing the transaction levy in 1989, CCA spoke about the need for an ad valorem or percentage of value type system as their preference. CCA had agreed to accept the introduction of a levy per head on cattle transactions as the first step, and said that an ad valorem system would be examined as the next stage to produce a more equitable livestock industry levy mechanism. That second step never happened.

Since its introduction there have been two major reviews of the Cattle Transaction Levy, in 2003 and 2009. Each focused on the size of the levy, and not how the funds were raised. In 2003, the levy was increased from $3.50 to $5.00, for a special strategic promotional effort called FTF (Funding for the Future). Later in 2009 this was reviewed, and voted-on at the MLA AGM which saw MLA members voting (72.5pc) for no change, meaning the levy remained at $5 per head.

During each review the levy mechanism was never discussed or re-looked at and the only issue debated was whether to increase or decrease the flat rate of $5 per head.

In short, since the adoption of the cattle transaction levy there has never been a review or change in the mechanism itself only in its absolute value – even though the wise heads of the industry at the time of introduction always thought the flat rate was step-one in the levy’s evolution.

It seems to me that a levy mechanism review is long overdue.

Set out below are some advantages, and disadvantages, I see in an ad velorem approach.

Advantages

As stated in my opening remarks, an ad velorem approach provides a more equitable payment model, that enables producers to pay a levy that is more in line with an animal’s true value at the time. During droughts like the present when farmers are dealing with high input costs and low livestock prices, the levy is more affordable, while during times of higher cattle prices and lower input costs with abundant feed, producers have a greater ability to pay higher levies.

One reader following my last paper made special reference to the need to focus on markets where Australia gets the best value for our beef, and not on volume – in other words looking for and promoting niche, high-value product. An ad valorem duty helps identify where real value lies and where as an industry we should focus our marketing and research dollars.

Niche high-end producers have a right to sit at the industry table when discussions on how industry funds should be spent. I believe an ad valorem levy gives authenticity to this right.

An ad valorem levy also ensures that MLA funding is more evenly spread over good and bad years. At the moment large funds are collected during droughts as females are turned off in large numbers, and less funds are collected during herd rebuilding periods, creating a disruptive revenue stream.

This unstable revenue collection system plays havoc when putting into place long-term funding programs in both research & development and promotion campaigns. An ad valorem model provides a more sustainable and steady revenue stream that is easier to plan around, and helps ensure minimum funding disruptions.

The irony with the current flat rate system is that the levy’s maximum collection period is during drought when farmers and producers have the least control over input costs and quality.

Some may argue that drought is when we should be spending our marketing dollars as cattle prices are at their lowest, but I disagree and believe this is a misnomer. In drought, the market is driven by oversupply of low-yielding under-nourished cattle, and it is hard to promote an article that is drought affected in this way.

In contrast, in good times when pastures have rebounded farmers can produce an animal to specification and meet market requirements more consistently, and it is at this point when we should be promoting the best quality beef and maximising returns, giving us an opportunity to be a price-maker and not a price-taker in global markets.

An ad valorem duty I believe is also crucial for the beef processing sector. In the past during periods of intense rebuilding and low cattle throughput, processor margins are often tight, or negative, and so the ability for processors to spend their own money on marketing and promotion becomes limited due to tight cash flow.

Access to healthy industry funds under an ad valorem levy during low cattle throughput would ensure that the processing sector in collaboration with broader industry can effectively maintain promotion campaigns during these harder times of low throughput.

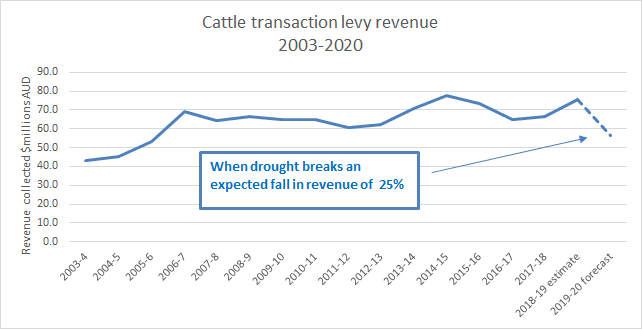

The following graph highlights the change in revenue from the cattle transactions since 2003. I have estimated a 25pc fall in levy revenue when the current drought breaks, based on a 16pc fall in slaughterings and a 14pc fall in transactions (I have used previous periods of drought and rebuilding phases as a guide).

The net effect is a $19 million fall in revenue from the current cattle transaction levy revenue stream, yet under an ad valorem system this revenue would not fall.

The disadvantages of an ad valorem system

My concern is that any change in how levies are collected can often turn into a political football match, as most sectors of the industry push hard for what is best for them. But ultimately I think a system that is based on value is possibly the fairest.

Some of the potential disadvantages I see are as follows:

The segment of the livestock sector that may have genuine concern with an ad valorem levy is the high-value segments such as Wagyu and studstock producers. That is why I believe a cap of $8.00 per head is important, so that these sectors of the industry are not seen to be ‘disproportionately’ contributing to industry funds.

It is important to note that high-value animals do not always mean a good margin, and that at times margins can be tight, even at the high quality end of the market. So a cap ensures that the contribution from the high-end of the market is more equitable.

Difficulty in collecting the ad valorem levy was raised back in 1989 when the levy was first introduced, but this has proven not to be the case with Australia’s mutton and lamb industries, which already have an ad valorem levy of 2pc of sale price in place. The proposed ad velorem cattle transaction levy of 0.5pc seems to be cheap, based on the proportionate value of each animal. I believe that like the sheepmeat industry, the cattle sector could easily adopt an ad valorem levy – in short there is precedent within the Australian livestock industry.

Other agricultural industries have ad valorem duties

The ad valorem levy mechanism is used not only in Australia’s sheepmeat sector but also in the Australian wool industry, which like sheepmeat has a 2pc levy on the value of the product.

In contrast, the Australian dairy sector does not have an ad valorem levy, but a similar flat rate levy of 10.05c/kg based on milk fat and protein produced – an agreed conversion formula from liquids to solids is used. Given the homogeneous nature of milk, this method of collection is simple and has been in place since 1986.

Some dairy farmers also question the disproportionate nature of this levy, and like cattle producers find that during low milk price periods and times of high input costs, this can be an added burden that many feel they can’t afford.

Conclusion

I think the need to review the current cattle transaction levy is long overdue, since its introduction 30 years ago in 1989. There is a need for a more equitable system that ensures farmers pay a levy that reflects their returns at the time of sale – in drought this levy should be lower and in good times higher.

The value estimate I have used at 0.5pc obviously needs further work on it, and the cap of $8.00 per head to ensure that funds are adequate at these levels, but the concept is what is important and the strategic advantages this model gives to us as an industry.

An ad valorem levy would ensure a more sustainable revenue model that makes funds available in a more proportioned way and provides industry funds when they are most needed for both promotion and research.

Ideally, as an industry when more favourable conditions return, we can produce the quality product that under an ad valorem levy matches the strength of good marketing and thereby maximising industry returns – giving us a rare opportunity to be a price maker and not a price taker in global markets.

As stated, the need to focus on our strengths and niche markets is made so much easier when the funding model reflects this. The ability to produce quality meat and promote it at the right time requires having funds and the ad valorem model enables that.

Just as importantly, I think it brings the farming and meat processing sectors closer together and to work collaboratively under an ad valorem model as each sector relies on the other at varying good and bad times to contribute.

I think our industry forefathers knew this in 1989 when they described the current cattle levy system as the first step in the process, and the move to an ad valorem levy as the final step.

I think we, as an industry, are ready for it.

* The $5 Cattle Transaction levy applies to each transaction through the chain on grassfed and grainfed cattle down to 80kg liveweight, destined either for slaughter or live export. Bobby calves < 80kg are levied at 90c/head.

Next week: Beef Central talks to former CCA executive director Justin Toohey about levy models.

Transaction levies each time an animal changes ownership look to me to be very like revenue gouging and have an anti-competitive element which disadvantages significant portions of the industry and advantages those who are vertically integrated. By making $5 levies each time an animal is sold the value of the animal is reduced at each stage of the pathway to its final processing and that value reduction becomes cumulative. In many production systems cattle can change ownership from weaners, to backgrounders to feedlotters or grass finishers and finally processors. Four levies or perhaps more than that if traders are involved, are gathered from each animal. Vertically integrated systems may even only have to pay one levy as ownership is maintained throughout the production system. This is not a fair system and changing to a value harvesting percentage basis for a levy does nothing to address the fundamental flaw of taxing some animals multiple times and others only once. The transaction levy adds costs to each producer along the supply chain and provides a cashflow to MLA which is disproportionately skewed to harvest cash from any production system that involves multiple stages of ownership of animals. I suspect that most vendors would prefer to have the $5 in their pocket as a reduced cost of production than taken out of their pocket to support the organisations that benefit from current practice.

This suggestion, if adopted , would more than likely create a differential levy system. Whilst the suggestion is feasible for the cow/calf component in general (particularly in northern states) where the drought induced price reductions occur and it provides a form of averaging of the levy, others will be paying $8 all the time. Likewise cattle finishers (grain and grass) will be locked in at the top indefinitely. Remember the grain levy is separately recorded now and therefore would for certain trigger the differentiation. Furthermore imagine the bun fight across the rest of the industry given it can’t now agree on its own representation model let alone the levy.

Of course, you are right Simon. The ad valorem levy mechanism is fairer in the spread of raising funds for marketing and research from cattle producers. Your arguments are sound. However, self-interest within sections of the industry will make it difficult to realise a change.

We question your suggestion Australia could be a price-maker in global beef markets. For as long as I have been in the industry, the US market sets the global beef prices in FMD-free markets. Conversely, Australia is a price-taker. While Australia is a significant player in the trade of beef products into FMD-free countries, its volume is insufficient to set price.

On another matter, producers are tired of delivering such large annual levies for various users, but particularly MLA, without any say in how the levies are spent. Too often we witness waste in MLA expenditure. The Australian Cattle Industry Council calls for the establishment of a new company, Australian Cattle Producers Corporation, to receive the levies collected and decide how they should be spent. It should be owned by the producers and its directors elected democratically from producers across Australia.

This would be totally consistent with the process used by processors and live exporters to receive and spend levies collected in their industries. Why are cattle producers by-passed in deciding how the levies are to be spent?

Just adding to Grant Pipers comment. The rise and fall of levy stream caused by seasonal variability is managed by putting excess levy funds into reserves for later use when cash-flow is tight through less transactions. That happens now in MLA and in most businesses.

John Wilde is also correct in pointing out that sale price does not necessarily reflect profitability. Beef Central regularly reports the low margin in the feedlot industry. Under Simon’s scheme a $30 margin would be reduced by 10% if the levy goes from $5 to $8 on a $1600 plus value animal.

We are a diverse industry with a range of production systems and supply chains therefore no system will be perfect for all. The current system is simple and transparent. There is nothing new in Simon’s arguments that would convince me to change.

Incredible to see the legwork going in now to ensure the privileged position of the MLA and multinational processors, worried about the post-drought costs to them. I see little compassion for the low drought prices producers are being paid now. The large revenues being garnered now by processors and MLA should be budgeted to last through the lean period afterwards, as must farmers. ‘Socialise the costs and privatise the profits’ is big business mantra these days. Personally, I would like to see the levy/tax removed, or significantly reduced as currently it undermines the emergence of a true producer industry lobby group. Failing that, the levy with additional Public funding should pay for all meat grading and inspection services – that would be of direct benefit to producers, consumers, and foreign markets by guaranteeing consistency of description.

You won’t get any opposition from across the industry about the need to return to government-supported meat inspection, Grant. All of Australia’s major export competitors have meat inspection systems totally, or at least heavily undewrwritten by government support – for reasons of socialised community benefit. As outlined in this earlier article, Australia’s government-regulated inspection and certification costs are 3.4 times higher than those in the US and 4.5 times higher than Argentina. In Brazil these costs are fully-funded by the government and are not passed on to processors or the industry. Both the US and Brazilian governments cover around 95pc of these fees. The industry’s recent Cost to Operate Report found that one of the key contributing expenses is offshore inspection fees, adding around $110 million in costs each year. Editor.

Or alternatively Simon we could make things a lot more simple and get rid of the levy altogether.All those in favour SAY…”AYE”.

There is also a need to rethink the percentage share apportioned to marketing and R&D

The one thing that producers have control over is their productivity

If we use the basic model of

Profit equals production by price minus costs

Then R&D contributes to production and costs improvements whilst marketing only contributes to price

In most markets we are basically price takers

Thus there is a good case for apportioning a much greater % of the levy to R&D as it contributes much more to the bottom line

Always arguable Simon!

However some disadvantages are that the levy stream would be harder to predict as it would not only vary with the numbers traded but also the value.

Many producers are also traders and the margin earned on a prime animal is often less than the price paid. In other words to set the levy as a percentage of the final price, say $1800, when the margin earned might only be $300 would lead to claims of unfairness.

I recall the discussions well and the fairest proposal was the ‘Leckie’ plan which worked like the GST but was rejected due to its complexity.

The current system, warts and all, is the simplest to administer and understand, and it will take good arguments to change a well established system.