While some question whether humans are supposed to eat meat, a University of Melbourne professor in food science and human nutrition says the archaeological record is unequivocal.

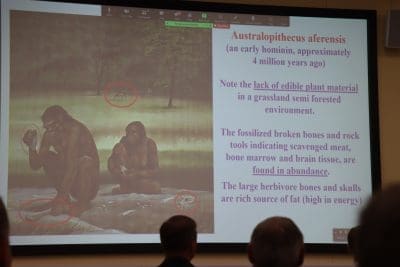

“Clear and abundant” evidence exists that hominins, our ancestors, began eating meat about four million years ago, Professor Neil Mann explained during a presentation to the recent Societal Role of Meat Summit in Dublin.

Not only was this necessary to enable early humans to survive the move from jungles to savannah environments, it also led to physiological and biochemical changes, enabling humans to evolve larger brains while expending less energy on digestion.

Not only was this necessary to enable early humans to survive the move from jungles to savannah environments, it also led to physiological and biochemical changes, enabling humans to evolve larger brains while expending less energy on digestion.

While our jungle dwelling pre-human ancestors were predominantly plant eaters, this was not an option in the more open savannah grasslands where grasses containing non digestible cellulose was the predominant form of plants.

Professor Mann also explained that meat is the major source of bioavailable iron and zinc in human diets, and meat and fish are the only source of functional B12 in diets.

Evidence is also clear that meat is essential to the brain structure, function and health of modern humans, Prof Mann said.

For the past 30 years Prof Mann has studied anthropology, food science and human nutrition, and has authored and co-authored numerous journal articles and scientific papers and a peer reviewed and referenced textbook on human diet evolution.

Outlining when, and why, early humans began eating meat, he explained that until the Pliocene era (the epoch spanning from 5.3 million to 2.5 million years ago), the ancestors of modern humans were largely “frugivorous” jungle dwelling primates.

That is, herbivores which ate high quality plant foods such as wild fruits and flowers and new shoots of plants, much like primate relatives in jungles still do.

(He also pointed out that many people may not realise that modern day chimpanzees also eat meat, in forms such as eggs, grubs, insects and small mammals.)

When our diet changed

A period of global climate change over several thousand years during the Pliocene caused areas of jungle to shrink and grassland savannahs to open in their place – into which some primates, including our predecessors, were forced to venture.

That is when our diet “really changed”, Prof Mann explained.

“Going out into the grasslands, the food supply wasn’t there anymore,” he said.

“Going out into the grasslands, the food supply wasn’t there anymore,” he said.

“We had to change, we had to find something different or we weren’t going to survive and that is when we started to become more highly dependent on animal foods in our diet.”

There is now clear archaeological evidence that about four million years ago these early human ancestors became scavengers, and used early stone tools to crack open the bones and skulls from the carcase remains of herbivores killed by large carnivore animals, so they could access and eat the bone marrow and brains within.

This provided a food source that was mostly fat and high in energy.

As early human ancestors began to develop bigger brains, they also began to develop hunting techniques, with archaeological evidence showing our pre-human ancestors had progressed to hunting animals for meat around two million years ago.

Data collected as far back as the 1990’s shows that around two million years ago, human ancestors had “a strontium calcium ratio somewhat like a hyena” – “So they were pretty much carnivorous, or highly carnivorous’ by that stage,” Prof Mann said.

Then about 60,000 to 80,000 years ago came the “out of Africa experience” where humans left Africa and spread around the world, followed by the development of agriculture in a few different locations around the world around 10,000 years ago.

(How do we know this? “There are literally hundreds of laboratories all around the world working in this area”, Prof Mann pointed out, collectively employing thousands of highly trained scientists building on decades of research and data. The use of forensic technology such as electron microscopes, cranio-dental images, gut morphology and analysis of isotope content of teeth and bone remains has provided a comprehensive picture of our ancestors and what they ate).

How “Optimal Foraging Theory” changed humankind

Before venturing out into grasslands, all of our ancestors ate plant foods, and ate them by the “bucket load,” Prof Mann said.

Part of the problem with moving out into grassland environments was that hominins (early pre-human bipedal primates) now had to find food regularly, unlike in the jungle where “green pickings” were always readily available.

With the shift to open grasslands came an imperative to eat foods that provided a greater energy return than the energy required to obtain it.

This is referred to as “optimal foraging theory”.

Plant food provided lots of micronutrients but not the energy return. Out on the Savannah early hominins “ had to get the animal foods to actually provide the energy they needed.”

In a recent study scientists calculated the energy return received from various foods by indigenous peoples in South America and the energy they had to spend to gather them.

Of the 10 top foods that provided the “best return” in terms of kilocalories per hour, seven were from animal foods.

Evidence does not support ‘plant good, animal bad’ mantra

Explaining how his own interest in this area developed, Prof Mann said that, “like many nutritionists and dieticians around the world” in the 1980s, he had been trained in the prevailing but “very unscientific and almost Orwellian mantra” of “plant food good, animal food bad” when it came to human nutrition.

“And that is all we thought.”

However, the evidence was telling a different story.

Illustrating this was a study conducted by his PhD supervisor, Professor Kerin O’Dea, one of Australia’s leading nutritionists.

The study followed members of aboriginal groups, closely monitoring what they ate, and analysed the impacts of different food sources on their general health.

They found that when aboriginal people left the western diets they were eating in towns and ventured back out into the desert to hunt and gather for months at a time, their diets changed to comprise mostly animal food, because that was what was mostly available in the desert.

In fact, 64 percent of the energy in their diet came from animal sourced food when in the desert.

“What did she observe? They lost weight, their blood glucose levels fell, cholesterol levels fell, blood pressures fell, in fact the exact opposite of what we assumed would happen.

“That made us think, well what the heck is going on here? This is not what we’re trained to believe.”

In effect, he said, it was not rocket science: “The things that make your cholesterol go up for example are not in lean meat (which is what game meat is).

“These specific saturated fats are in the meat fat and in palm oil (used in processed foods), but the cholesterol which is in meat doesn’t raise your blood cholesterol.”

No society ‘completely vegetarian’

In another study, Prof Mann joined several other research professors around the world interested in diet and anthropology to collect data already in existence from 181 contemporary hunter gatherer societies.

“We looked at that data over five years and analysed it, and we came up with a subsistence pattern of 65pc energy from animal foods and 35pc from plant foods, quite the opposite of what you actually read about it in unreferenced books,” he said.

“There was no such thing as a complete natural hunter-gatherer vegetarian society.

“There was no such thing as a complete natural hunter-gatherer vegetarian society.

“Many untrained people may tell you that humans are vegetarians, but we couldn’t find any natural hunter-gather society in the world that was completely vegetarian.”

The ‘extremes’ were the Inuit peoples of the arctic regions and the Kalahari bush tribes of Africa – the former were almost 100 percent carnivore, the latter primarily herbivore due largely to the unique year-round availability of Mongongo nuts, high in protein, fat and carbohydrate, but they also use bows and arrows to hunt game.

“In every case of those 181 societies, the pattern of food procurement followed mathematically perfectly Optimal Foraging Theory,” Prof Mann said.

“They concentrated on things that gave them most energy return.”

How meat changed us

Prof Mann said the shift to a meat diet four million years ago led to biochemical and physiological changes in humans including the growth of larger brains which was also matched in changes to digestive systems which enabled them to digest animal foods and invest less energy digesting foods.

In short, the gastrointestinal tract in humans condensed to become smaller and simpler. The structure of human digestive systems today is almost the same as most carnivores, he said, though humans have a greater propensity to use plant food than most carnivores.

As the gut size got smaller, diet quality had to increase. The only way that can happen, he said, are with foods that are more easily digested.

“That spells animal foods,” he said, noting there were “many papers on this”.

“We’re very good at being omnivores,” he said. “Even when you compare us to cross primate relatives in the jungles we’re different, we have moved away from what they are.

“They use their colon as a substitute fermentation chamber, and a small residual cecum that they can also use to ferment cellulose into digestible carbohydrate.

“We have most of the volume of our digestive tract mostly in the small intestine, more like a carnivore and lack a cecum or rumen necessary for breaking down cellulose”

Human brain function depends on meat in the diet

Prof Mann said human brain function “really depends on meat in the human diet”.

“There are things in meat that you don’t get from plants or you don’t get very well from plants,” he said.

This included a balanced intake of amino acids, iron and zinc Vitamin B12 and the longer chain forms of Omega 3 fatty acids.

One study he conducted showed many vegetarians and vegans actually eat more iron than meat eaters, through plant foods and supplements, but remain iron deficient.

While some plant foods can be quite high in micro-nutrients, bioavailability compared to meat is very low. “Iron and zinc, we all know they’re much better absorbed when they’re protein bound, a situation that occurs in animal foods not plants,” he said.

“When we did the dietary analysis, they were eating more iron, because they were eating lots of plant foods, but they weren’t absorbing it and that just shows you how much difference there is in absorbing iron from animal foods versus plant foods.”

Modern humans have evolved on a diet high in animal foods

In summary, he said, modern humans have evolved on a diet high in animal foods for over 3.5 million years, possibly closer to four million years.

Meat is the major source of bio-available iron and zinc in our diet, and meat and fish are the only source of functional B12 in our diet.

Iron, zinc, vitamin B12 and Omega-3 fatty acids (long chain forms) “have been shown repeatedly in studies” to be of critical importance to brain structure and function.

Recent research has shown a “triple whammy affect” on brain function, Prof Mann said, with people whose diets are deficient in long chain omega 3 fatty acids, low in B12 and high plasma homocysteine at higher risk of suffering from brain atrophy and dementia.

RELATED ARTICLES:

International scientists gather in Dublin to clear air on meat and dairy science

Scientists urged to sign ‘Dublin Declaration’ supporting balanced view on meat

The essential role of meat and dairy in healthy diets