Simon Quilty

This report is the final instalment in a three-part series compiled by meat industry analyst Simon Quilty looking at the potential impact of African Swine Fever in China. Today’s report focuses on the potential need to restructure the China pig industry and the critical role imported pork, beef, sheepmeat and chicken will play in managing the transition process as China tries to get ASF under control.

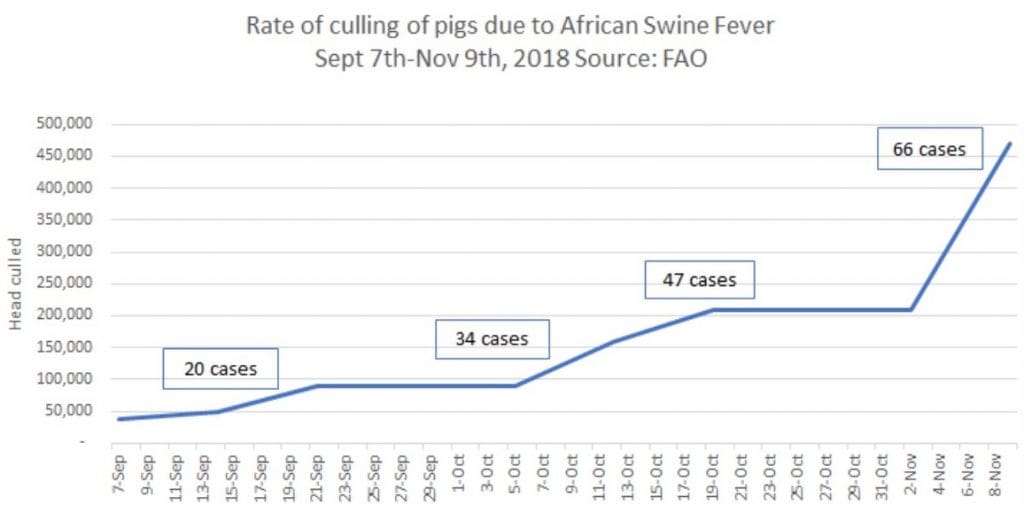

LAST Friday the Food and Agriculture Organisation released its latest African Swine Fever report, stating that the number of culled pigs in China had increased in one week from 220,000 to 470,000 head. It should be noted that whereas the FAO’s earlier reports included both disease mortality rates and culling, the most recent FAO report now only reports on rates of culling. As one expert told me, he believes the rate of death due to AFS is now far exceeding the rate of culling hence the Chinese Government decision to report culling only to moderate the figures.

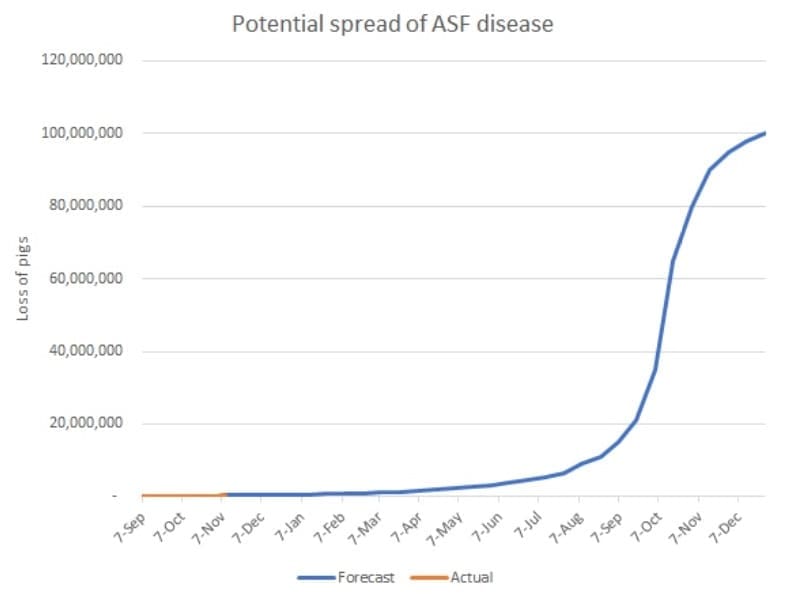

This graph to me highlights that the disease has entered a new phase as a ‘chronic epidemic’ whereby such epidemics move into an exponential growth period of spreading. I spoke with epidemiologists on this who mapped three potential scenarios, based on 12 months, two years and three years of culling depending on the success or failure of control methods. Most were of the opinion that within 12 months is the more likely scenario, given the rate of spread in the last 12 weeks.

Restructure of China’s pork industry is inevitable over five years

The Chinese pork industry as we know it today I believe will be very different in 2-5 years’ time.

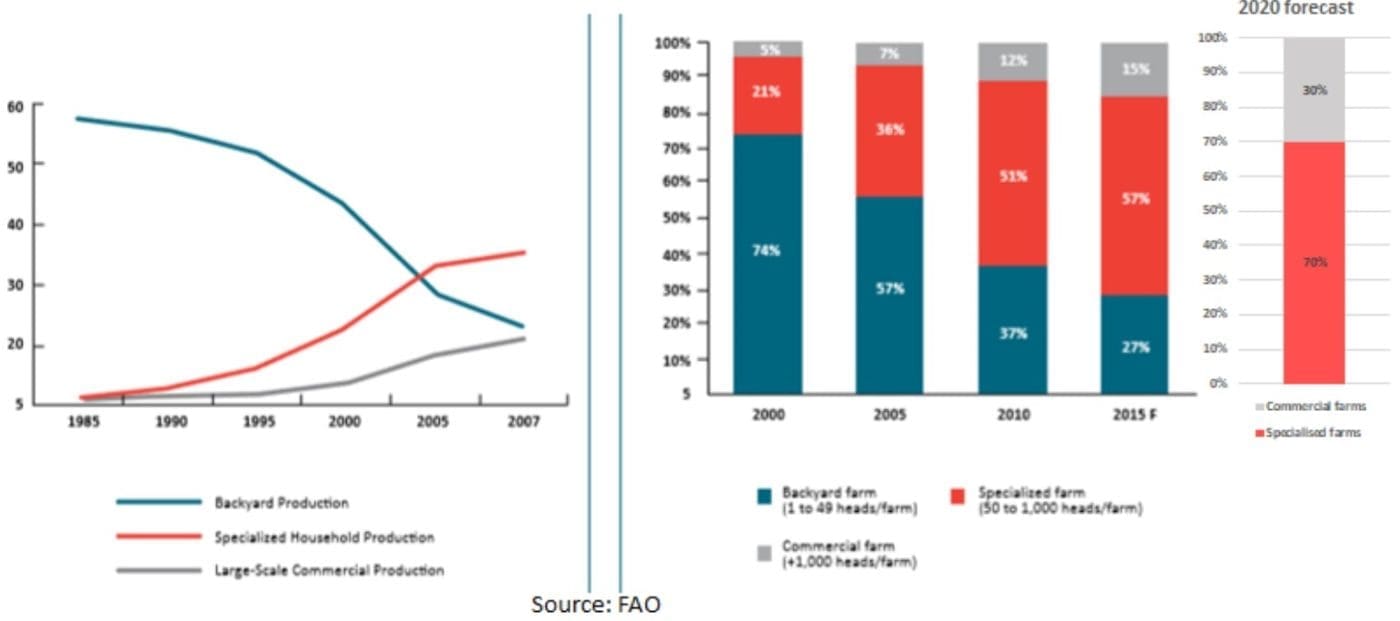

In recent years, ‘backyard’ farms have made up 27pc of China’s total pig herd size, or close to 116 million head. I can envisage that in 1-3 years. there will be no backyard pork production. This would happen because backyard pigs are the most vulnerable sector to the ASF disease and also are the most difficult to control, and the recent decision by the government to ban feeding food scraps to pigs is strong evidence of this. But in reality, as long as backyard pigs remain, this threat of spreading will always be there, so complete removal is the only true solution.

In the future, the growth of specialised farms and large commercial operations will enable the Chinese government to introduce disease controls far more effectively. The table above shows the gradual decline since 2000 and the last ratio is my prediction which shows 30pc large commercial farms and 70pc specialised mid-size commercial operations. It is the liquidation of the 27pc of backyard pigs (116 million head) that will occur in the next 12-36 months.

In the August USDA report on China, the following comments were made:

“If these AFS outbreaks continue, the only methods to control the spread are strict quarantine and mass de-population. As the outbreaks have already reached Henan Province, China’s primary swine growing region, it is possible these outbreaks could have a significant effect on 2018 and 2019 production.”

As one pork trader said to me regarding the culling of backyard pigs: “If the disease doesn’t get them, the government will.”

This week I have anecdotally been told that two provinces in southern China are now forcibly removing all backyard pigs, with or without the disease. This trend will likely to occur all over China as the government is fast realising it is the only means to contain the problem.

The potential impact of a 100 million head cull in 2019 and 2020

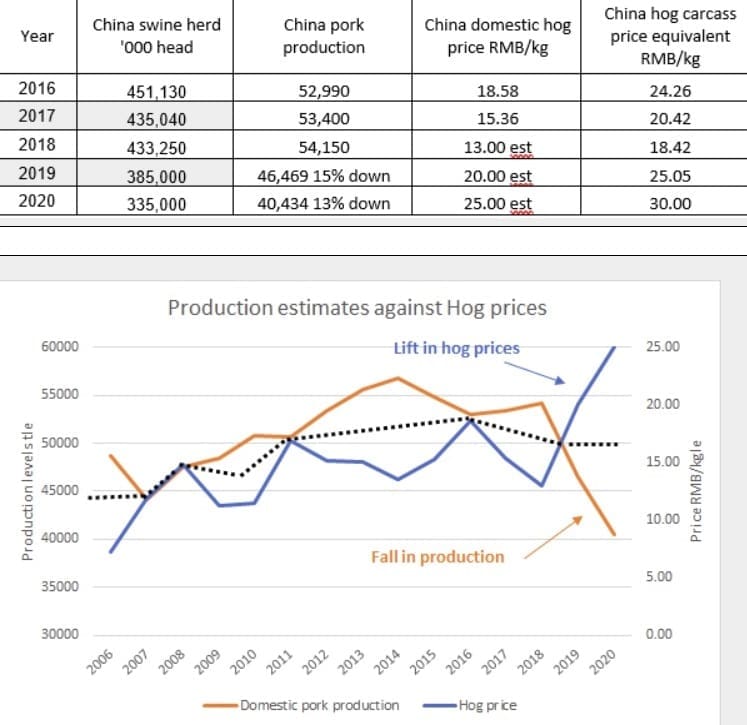

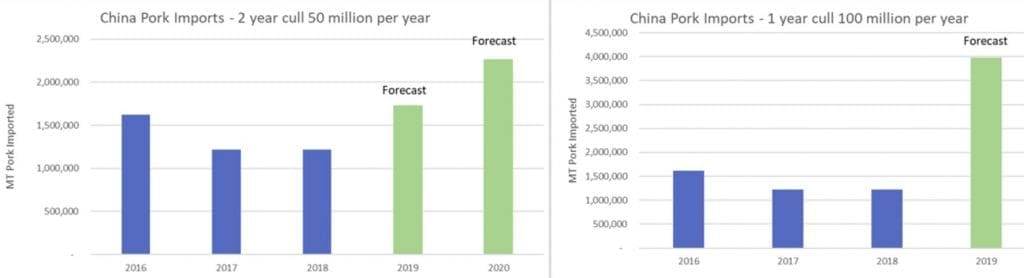

I have used a 50 million head pig cull/mortality loss per year in 2019 and 2020 as a conservative estimate of what would be a likely two-year cull/disease loss period. The estimates saw a 15pc fall in production in year one, that resulted in domestic hog prices increasing 53pc and a further 13pc fall in year two that could see hog prices lift a further 25pc.

Determining pork import volumes needed in 2019 & 2020

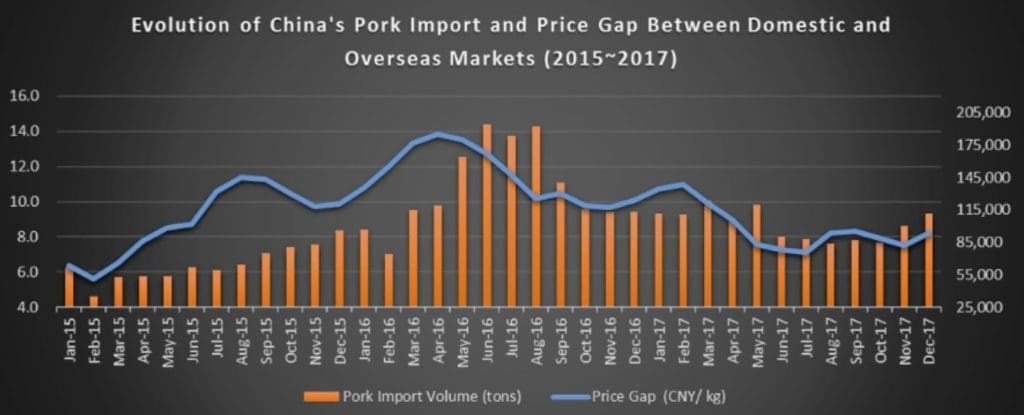

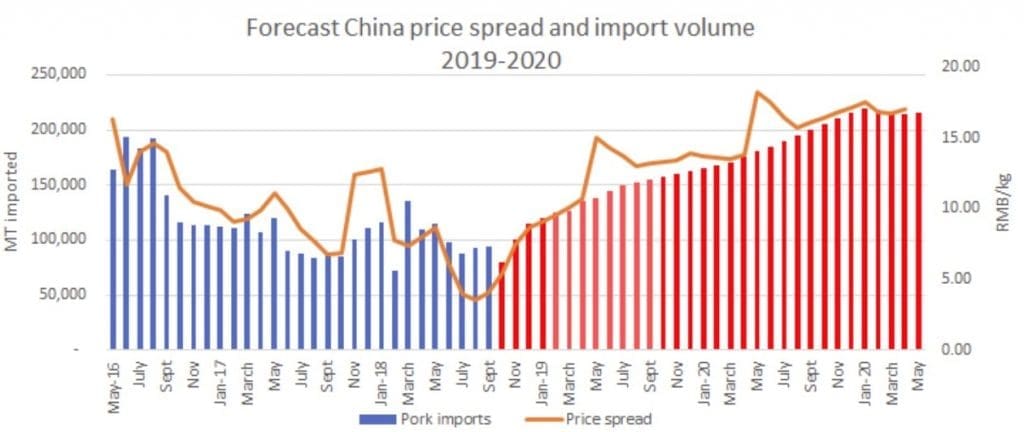

The following graph was published by the ‘The Pig Site’ in March this year with the analytical work done by Angela Zhang, head of Business Intelligence Division at IQC Insights a Shanghai-based consultancy that focuses on the pork industry in China.

What is so important about this analysis is the price relationship between domestic pork and import pork. In essence, the higher domestic pork is and the wider the gap between import and domestic pricing, the greater the pork imports. Readers should note in her graph below that there is a delayed affect, as the market responds to high domestic levels and a 2-3 month delay occurs as imports take that time period to be produced, shipped and entered into China.

I have used the same methodology using my own estimates on hog prices based on a 50 million pig liquidation in 2019 and a further 50 million head in 2020.

The issue with today is that these gaps may exist in China but are regionalised. I believe that due to quarantining, there are key demand areas that have gaps equal to or greater than 14 yuan/kg (equally there will be regions where domestic pork prices will be lower than imported). It is in these high priced regions that imported pork will find its way imported into during 2019.

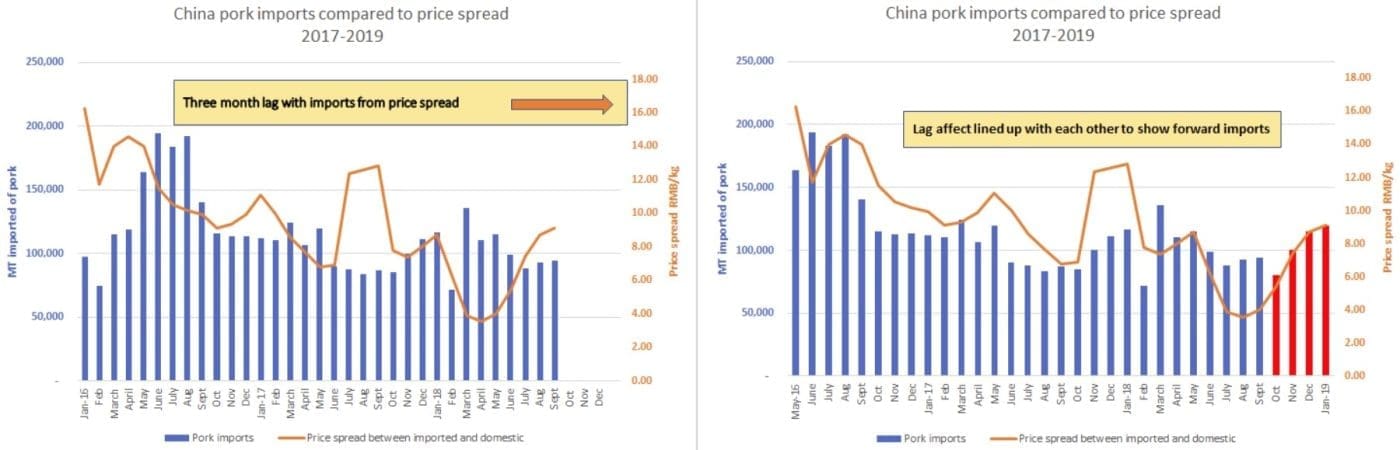

Using a similar methodology, I have outlined below the three-month lag that exists between China pork imports and the price spread between imported and domestic. To me, this is a self-regulatory system whereby the government and private enterprise work hand-in-hand to ‘keep a lid’ on domestic pricing, and when domestic pork pricing gets too high and the spread between imported and domestic gets too wide, the government implements an import program and instructs for imported volumes to be increased. This normally happens within 2-3 months, leading to a fall in domestic pricing. I believe this means of effective price controlling has been going on for many years.

When the spread forecasts are extrapolated out against the impact of the 50 million cull per year in 2019 and 2020, the results are as follows, with a dramatic increase in imports over the next two years.

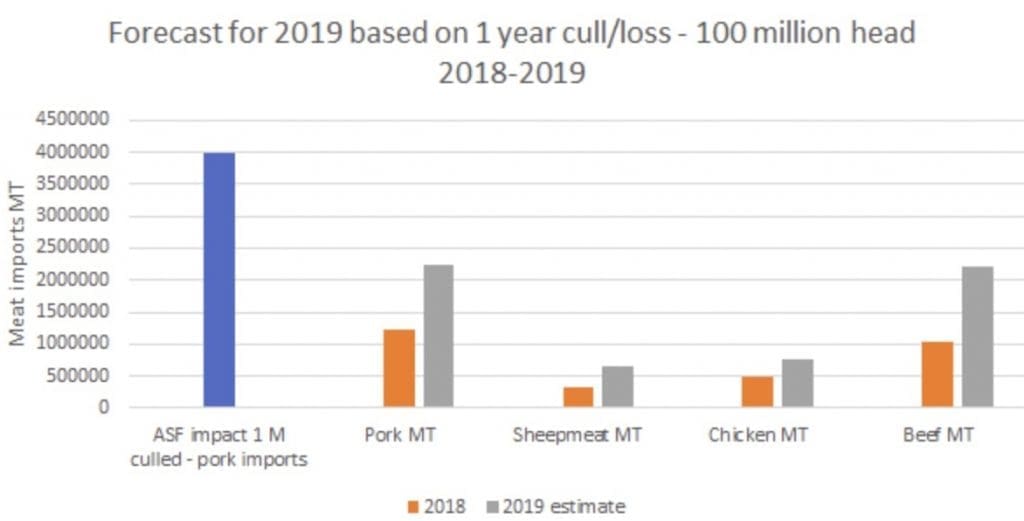

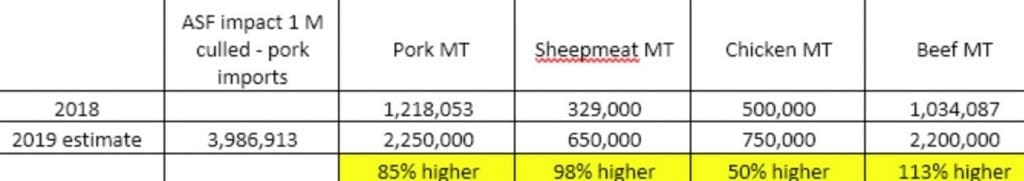

I have summarised those views below in terms of yearly imports, which I have estimated would lift the potential pork imports over two years by 41pc and 85pc or to 1.73 million tonnes and 2.26 million tonnes respectively. But if the cull/death rate should be 100 million head in 2019, this would see pork imports having to increase more than three-fold during next year.

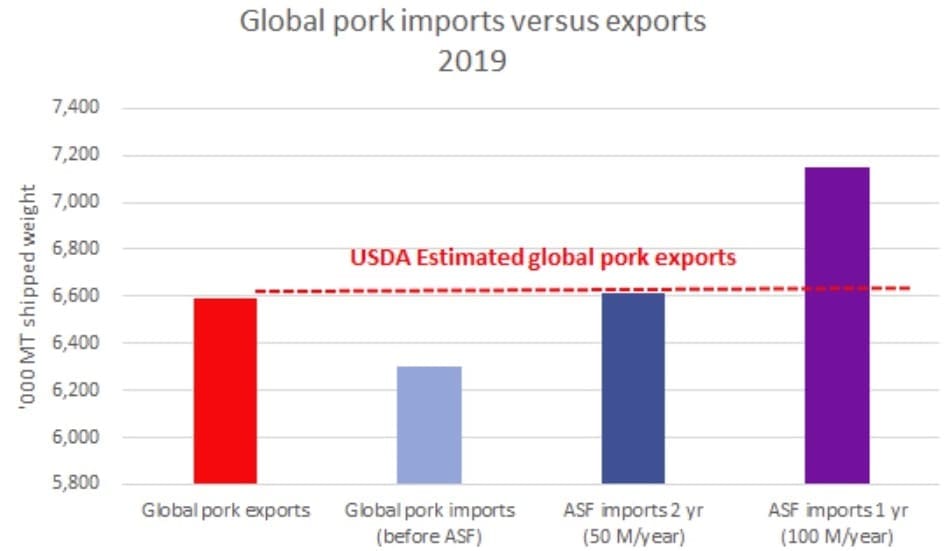

Is there enough global export pork to meet this potential increase in demand?

I have used USDA export estimates below for 2019 based on pre-ASF outbreak and showed how global exports might look against the impact on global imports with a two-year cull (50 million per year) and a one-year cull (100 million per year). The interesting point to note is that with a two-year cull, I have estimated that global imports would match global exports over two years, but if a one-year cull should occur, it would see a deficit of 556,000mt globally of pork – which beef, chicken and sheepmeat would need to play an important role in to meet China’s protein needs.

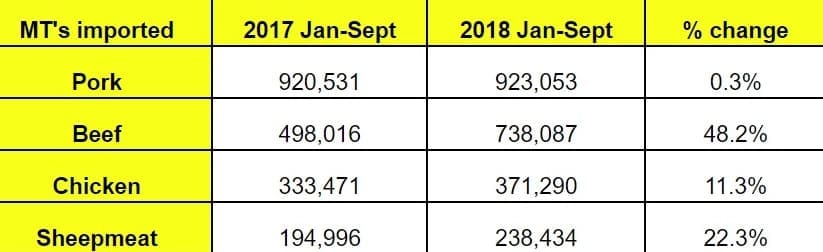

Beef, chicken and sheepmeat will play a crucial role in 2019/20 for China

The role of beef, sheepmeat and chicken for China’s potential pork deficit cannot be underestimated in the next two years – in particular if next year’s cull/death rate is greater than 50 million head.

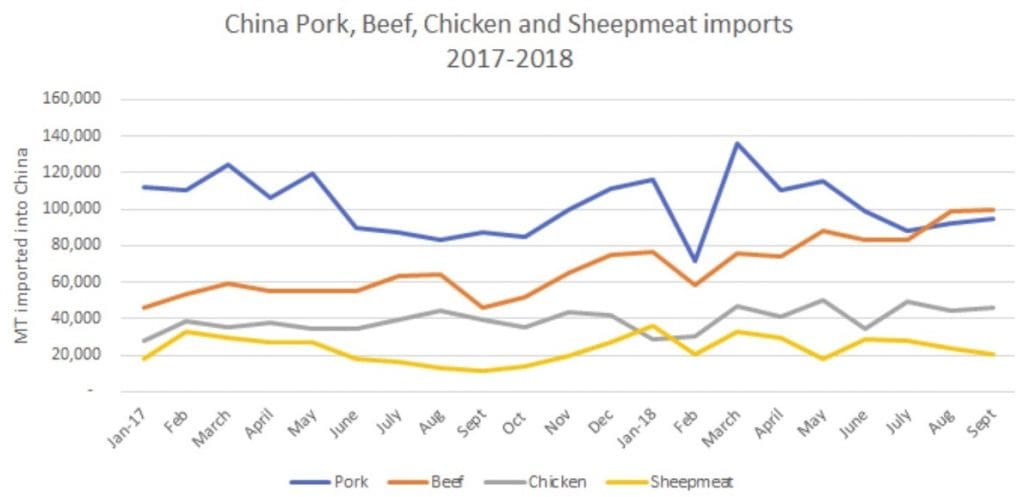

When comparing last year’s import figures with this year’s, beef is by far the largest winner with China’s beef imports up 48.2pc for January to September followed by sheepmeat which saw a 22.2pc increase and chicken an 11.3pc increase. Pork has almost remain stagnant.

Note that these shipment figures happened prior to ASF occurring, and given the early social media attention in the initial ASF stages that this trend is likely continue with more beef and sheepmeat demand expected for the next two years. USDA in the recent August report highlighted this fact and is forecasting a 3pc rise in demand with total beef consumption estimated at 8.6 million tonnes.

The potential driving force behind beef and sheepmeat demand in China has been the growing middle class, and the desire to spend the expendable income on perceived higher quality proteins. I believe the negative publicity around ASF will only amplify this trend.

USDA highlighted that the most recent beef per capita figures show China consumption is at 6 kg/person and that the world average is 8.6kg, meaning there is real upside for further growth.

What is notable this year is the dramatic increase in beef imports and the stagnant nature of pork imports in China, which reflects the increase in China’s domestic pork production of 3pc this year, which prior to ASF, was on track to see an additional 1.5pc increase next year.

This now, I believe, will be the opposite, due to culling/disease deaths see a pork production fall of 15pc and 13pc over the next two years. China’s beef production has this year been impacted by the culling of dairy cows as the dairy industry upgrades and the less productive dairy cows are diverted into beef supply. High beef prices in China and low milk prices have incentivised dairy enterprises to continue this trend.

Cull/disease deaths over 2 years

This, as stated, is likely to see global pork imports and pork exports be in equal proportion. The growth in imported beef I believe will continue at the current rate of increase of the last few years with the largest periods of import being October-December prior to Chinese New Year.

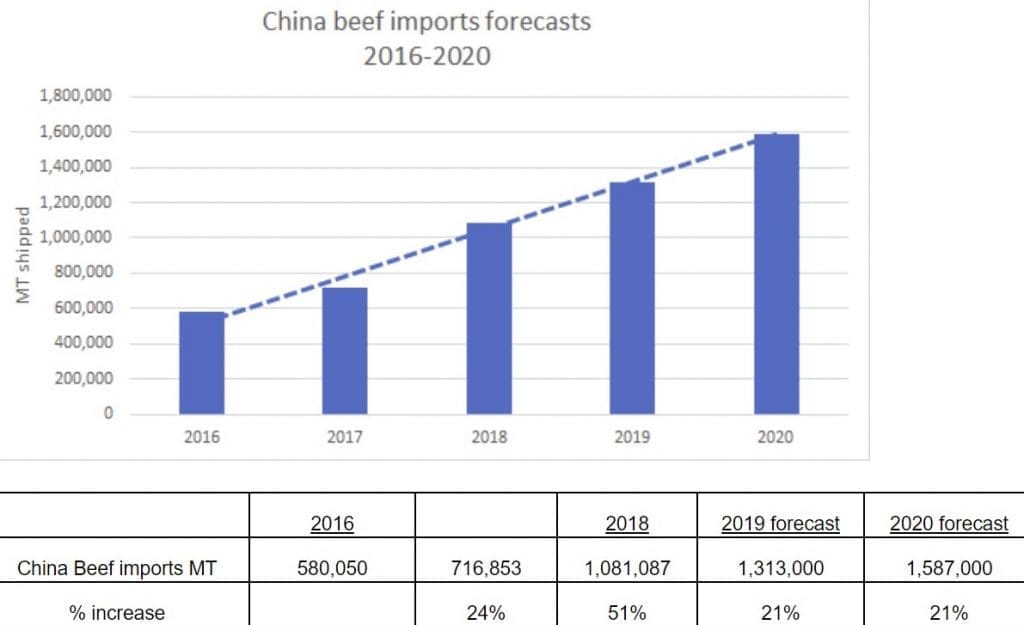

USDA forecasts for beef imports are estimated at 10pc growth – my estimates are based on 21pc growth which may seem conservative compared to the 48.2pc growth this year.

Cull/disease deaths over 1 year

This is the more challenging estimate given the expected shortfall in pork supply due to ASF and the likely requirement to fill the void. The role of beef as now being a critical part of the total equation but it should be noted that USDA’s China pork export forecast of 270,000t I believe will now be absorbed by China’s domestic consumption due to ASF.

This is reflected in the pork import figures below. The USDA also estimated that China’s pork import figures would fall 22pc in 2019 as domestic demand weakened and domestic production increased. Due to ASF the reverse is now likely, with a 15pc fall in domestic production. I believe demand is likely to remain weak, but the cull and impact of ASF and the large pig cull will more than offset the impact of lower demand.

Import table estimates due to ASF impact

Which countries are most likely to fill China’s beef, chicken and pork needs?

Beef imports –

The table above highlights that beef imports will play almost an equal role to pork imports in helping to manage China’s consumer needs, with both contributing close to 2.2 million tonnes over 1 to 2 years, depending on the type of cull that occurs.

When trying to identify which countries will be the key supply players in 2019 and 2020 to meet China’s protein shortage, I think in the case of beef, the most recent beef import data for September is the clearest indicator with what potentially lies ahead, with the following breakup:

- Brazil 40pc

- Australia 20pc

- Argentina 14pc

- New Zealand 11pc

- Uruguay 10pc

- Canada 1pc

- Other 4pc

The biggest challenge for Australia’s beef supply will be the limited number of meatworks registered for China, and also the fall in Australia’s production due to drought and the liquidation that has occurred. I am of the opinion as the overall import volume grows that Australia’s market share will fall due to these two key reasons.

Pork imports –

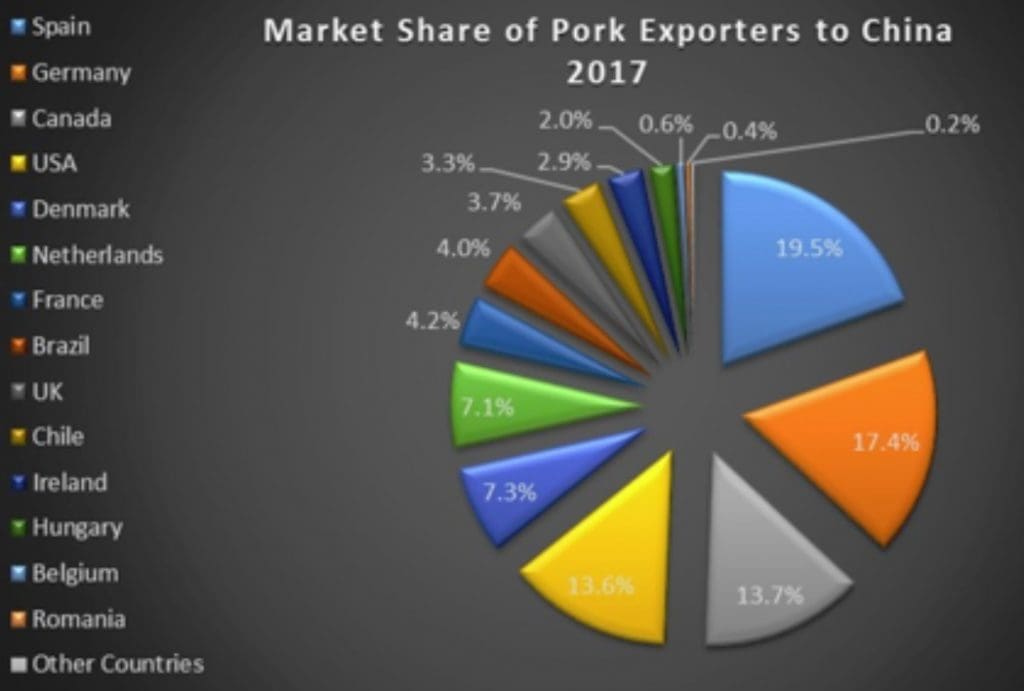

In 2017, China imported 1.2 million tonnes of pork meat and 1.2mt of pork offal. The EU was critical in meeting China’s needs with Spain, Germany, Denmark, Netherlands and UK (pre Brexit) all playing roles in both pork meat and offals. The EU supplied 65pc of all China’s pork meat imports and 54pc of their import offal needs. Canada, US and Brazil all played lesser roles in 2017 but were none the less important exporting 306,000t, 309,000t and 49,000t respectively.

In 2019, a similar situation may unfold, but there are several layers of complexity to global pork supply – namely that ASF also exists in the EU with Poland, Romania, Hungary and the Ukraine all having reported outbreaks in 2018. In addition, the tariffs place on US pork adds an additional 50pc in cost, which have made US exports fall away.

Should the EU situation worsen on ASF, and matters remain unresolved between China and the US on the trade war, then a shift towards Canada and Brazil seems inevitable – although for Canada, the challenge is being able to serve more volume into China given it already exports 63.6pc of all its pork production. This could see Brazil as one of the key suppliers left to meet China’s needs.

Sheepmeat imports –

Australia and New Zealand make up to close to 99pc of all China’s sheepmeat needs, with NZ having the lions share at 58pc and Australia at 41pc. The current China consumption rate is 3.4kg per person/year with the expectation that this will grow to 4kg by 2027.

In my 2019 estimates above I have forecast an additional 321,000t will be needed next year (under a one-year cull). The bulk of these sheepmeat exports from Australia is mutton and given the drought and that sheep kills are 30pc higher in Australia than last year, strong mutton prices and more reliance on New Zealand as a supplier is inevitable.

Chicken imports –

China’s needs for chicken prior to ASF was forecast by the USDA to be an additional 25,000t or 7pc higher. I have been more aggressive in my forecasts due to ASF and placed the imports at close to 50pc higher, as a cheap alternative to pork.

The expansion of China’s domestic poultry production has been hampered by HPAI-related bans which has limited the supply of imported stock and genetics. The most likely suppliers to China will be Brazil as the US remains banned due to HPAI avian influenza outbreaks in 2015, which also leaves the EU, Thailand and the Ukraine as important other key suppliers.

Conclusion

I would like to thank MIG – the Meat International Group in China – for their help in putting this report together along with the previous two discussion papers.

The complexity of African Swine Fever and its potential impact on the global protein balance sheet cannot be under estimated, nor the enormity of the impact of this disease on protein demand and supply for many years to come.

I have outlined two potential scenarios over two years in this report, but many experts believe this problem will be ongoing for ten years.

The need to restructure the China pig industry seems inevitable, and I am hearing anecdotally that this is occurring already in certain provinces. The challenge is getting an accurate estimate on this restructure, which I have put at 100 million head.

The role of imported pork, beef, sheepmeat and chicken are all crucial to ensure food prices are kept to reasonable levels and that the impact of culling and quarantining does not lead to enormous price spikes within China which in turn could see social unrest.

HAVE YOUR SAY