FOR years, pre-slaughter stressors and low glycogen levels related to nutrition have been seen as the principal culprits in dark-cutting seen in grassfed carcases at the meatworks.

But researchers are starting to zero-in on a number of other potential contributing factors that appear to be causing baffling seasonal spikes in dark-cutting results in southern Australia.

A group of beef and lamb producers attending a JBS Great Southern program supplier day in Launceston recently were among the first to hear about progress in some important new research into the topic, presented by Murdoch University meat scientist Dr Peter McGilchrist.

A trial using cattle from King Island and slaughtered at JBS’s Longford plant in northern Tasmania is unearthing some important new considerations – perhaps best described as hypotheses until more conclusive research is undertaken – in solving the dark-cutting challenge.

Dark cutting has a significant impact on the beef industry, estimated to cost producers Australia-wide 59c/kg on average carcase weight through downgrades and non-compliance, worth around $17 million to the production sector in 2014. More broadly, dark cutting costs the industry an estimated $55 million each year.

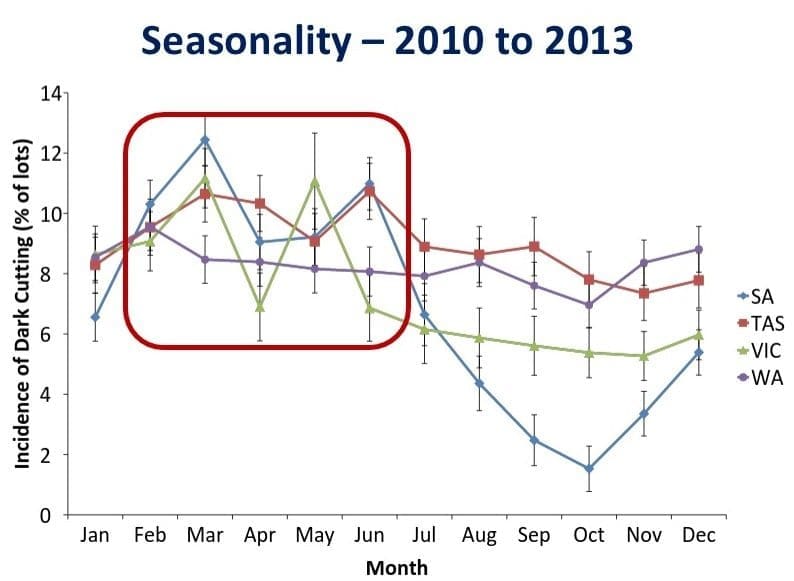

Dr McGilchrist illustrated the current situation using a sample of 184,000 MSA-graded carcases processed at JBS Longford since 2012, including some good seasonal years, and others no so good.

Like many other southern Australian MSA plants, yearly dark-cutting rates at Longford show a marked spike in non-compliance during the autumn period, from around March to July (see graph).

“Tasmania is not alone in this – we see similar elevated results during autumn in South Australia, Victoria and WA as well,” Dr McGilchrist told the Launceston meeting.

“And all this happens at a time when there’s likely to be rapidly growing green pasture, high in energy and protein. The cattle are doing well, they’re growing, so there should be no issue,” he said.

“So what the hell is going on?”

Dr McGilchrist said a lot was already known about the nutritional and stress impact on dark cutting, but researchers were now looking for one or more other factors that could be having an impact during the typical autumn ‘spike’ period.

“We concluded the impacts must be happening on-farm. Processing procedures, grading and distance to slaughter do not really change through the year,” he said.

In focussing on on-farm factors, researchers sought an area where there were lots of cattle coming from the same farms to the same processor, eventually deciding to use King Island as the research focus.

First hypothesis: magnesium deficiency

A series of possible causes were raised as hypotheses by researchers.

The first was inadequate magnesium, which for many years has been ‘in the background’ as a possible cause of dark cutting.

“We started thinking about sub-clinical grass tetany,” Dr McGilchrist said.

“We thought it was a possibility, because at this time of year there is an increase in intake of potassium and protein. Why would we care about these two things? Magnesium is one of those elements that animals have to continually consume. It’s not like copper which can be stored for a couple of months in the liver.

“If potassium and protein levels in the pasture are high, it reduces the plant’s ability to absorb magnesium. Minerals are complex, and often it’s necessary to look at interactions with other elements as well,” Dr McGilchrist said.

So how might high potassium and protein and low magnesium influence dark cutting?

Researchers are theorising that less magnesium in the plant, due to higher levels of K and protein, lead to cattle eating less, which means less energy intake and slower growth. Therefore a lot more of their intake is taken in body maintenance, meaning less glycogen being produced.

“With magnesium, it looks like a double-whammy: it puts less in, plus it causes more to come out. Animals with low magnesium have increased adrenalin response, in turn leading to increased stress – a classic cause for dark cutting,” he said.

Second hypothesis: Mycotoxins

A second theory surrounds the potential impact of mycotoxins in certain pastures.

Acute ryegrass staggers is an example of mycotoxins at work, especially seen in old cultivars of fescues and ryegrass.

Endophytes in the plant can produce mycotoxins, especially in older cultivars bred for drought and pest tolerance and hardiness.

There is a suite of mycotoxins present in such species that cause production losses in cattle.

“There’s already been a lot of research into mycotoxins and their impacts on production – but none of it has ever focussed on dark-cutting – and that’s where this project comes in,” Dr McGilchrist said.

Previous research had clearly shown that increased levels of mycotoxins will reduce feed intake, reduce weightgain and growth rate, and increase risk of heat stress. They can also reduce pregnancy rate, milk production and quality, and increased mortality.

Out of all those factors, it is the first four that will impact on muscle glycogen, and hence, potentially, increase dark cutting.

“Less energy in, and more energy out due to heat stress should mean more dark cutting,” Dr McGilchrist said.

Research focus on King Island

As part of the project, researchers focussed on about 3200 slaughter cattle of mixed ages, sex and breeds (66 lots in total) harvested from King Island over the March-June period and processed at the JBS Longford plant. Pasture, silage, blood and liver samples were collected and analysed, including presence of mycotoxins in pasture. Weaning methods, temperament, procurement method, pasture species, trace element supplementation, supplementary feeding, transport conditions, weather, liairage and other factors were also recorded. Almost 1000 blood samples were taken from the same animals both on-farm and at the slaughter floor.

Big variations in dark cutting were evident from week to week, reinforcing the point that properly conditioning cattle before they go through the pre-slaughter period is most important.

“No matter how rough the conditions were that week on the boat, or how far they had to be sent on the mainland, if they are conditioned well before despatch, they appeared to handle the circumstances better,” Dr McGilchrist said.

Cattle that had been supplemented also produced a lower incidence of dark cutting, despite receiving hay or silage that was lower in energy and protein than available paddock feed. The theory surrounding this is the habituation effect of interacting with humans, tractors etc, reducing stress.

Another clear trend was the impact of lifetime yardings (human imprinting) on dark cutting, showing a distinct decline as interaction through yarding, weighing, confinement in the yard etc rose.

Mineral results

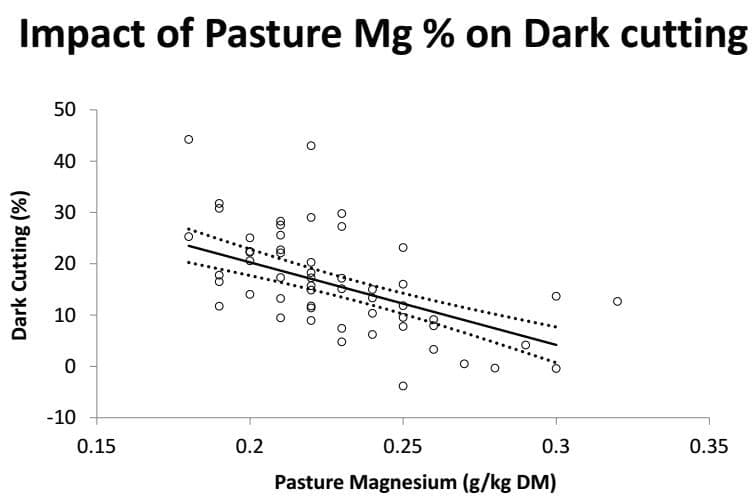

The trial showed a clear decline in rates of dark cutting as pasture magnesium levels increased*. (* Readers, please note: the original version of this sentence had the word ‘decreased’ instead of ‘increased.’ – Now corrected – Our only excuse is the pre-Christmas rush! Editor).

Dr McGilchrist described this as a “really great finding.”

“It appears to be a very seasonal impact at the break in the season heading into autumn.

The research data was also collected in the period when researchers suspected there might be some grass tetany issues, but no link was seen between the Grass Tetany Index (the relationship between magnesium, potassium and calcium) and the percentage of dark cutting.

“What that tells us that magnesium is acting on its own, and not in response to a greater level of K reducing the magnesium’s absorption, which was the original thought,” he said.

Interestingly, a clear link was shown between an increase in crude protein level and a rise in the level of dark cutters.

“But logic tells us that crude protein is good – we want more crude protein, it makes them go faster,” Dr McGilchrist said.

He said the response being seen was possibly being driven by a few factors. The mechanism was probably that increased protein was reducing magnesium uptake, or that increased protein might be increasing plasma ammonia, and also urea (glycogen storage). Both were ‘energy expensive’ to get rid of, and may also reduce insulin sensitivity, used for storage of nutrients and minerals.

“In effect, it kind of sets the animal up to be a little bit diabetic. But more research needs to be done in both these areas to learn more,” he said.

Blood and liver testing also suggested that while selenium levels were adequate, some sale lots were not getting enough copper, which could impact on growth rate and dark cutting.

Zinc was another interesting result. Liver zinc levels were deficient in quite a number of lots, which would require more research to understand. “But zinc, copper and selenium are all elements that are stored in the liver, and are elements we can do something about,” Dr McGilchrist said.

Mycotoxin impacts

Dark cutting was shown to increase as the concentration of one of the family of mycotoxins, Ochratoxin A, increased – even at very low concentrations.

A lot of the other mycotoxins measured were either in very low ranges and not causing an impact, or in the case of ergot alkaloids, present in 92pc of pastures in ‘high’ doses, but producing no dark cutting impact.

“But perhaps one or two of the mycotoxins are producing more of a ‘dull headache’ in results, rather than a ‘migraine’, through the March-June problem period,” Dr McGilchrist said.

“Certainly we need to do some more work in this field of mycotoxins and their impact on dark cutting. But more broadly, mycotoxins are produced by old rye and fescue cultivars, and it’s those persistent ‘mongrels’ that hang around for 20 years that we need to have a look at. They impact on not only dark cutting, but also reproduction, especially when feed is short.”

More mycotoxins are still being analysed, and eventually it is hoped that a full suite of information can be produced on mycotoxins of interest in the dark cutting area.

“The solution is to plant new well-bred rye and fescue cultivars with novel endophytes that minimise mycotoxin risk, and do not impact on production,” Dr McGilchrist said.

“They improve weightgain and reproduction rates, allow earlier turnoff of finished stock, which also contributes to reduced dark-cutting, and increased carrying capacity on those pastures, compared with old varieties.”

Mycotoxin binders, like Biomin’s Mycofix product, might also play a role.

Acknowledgements

“Dark cutting research work like this is not easy, as it requires big numbers, big expense, and big time commitment in data collection,” Dr McGilchrist said.

“I’d like to thank MLA for funding this important research; JBS and its supplier network across King Island, the staff at JBS Longford for supporting us and helping us with this project, to get the vital data that we needed to do this work.”

Well done you have reached this far

I wish we reconnect another time

Regards Stephen.

A good piece, with more good information.

However there is more to it, starting from weaning to slaughter. Handling in the hours prior to slaughter, including transport, possibly after slaughter. Feed supplements including protein requirements.

Meat works don’t really know it will be dark cutting until its dead on a hook. Maybe it should be included into grinding beef only, but meat works can’t afford not to sell that particular body. Other than make tallow, we can’t expect the meat works to take the fall, it should be a joint problem. Rob, I am not a butcher, nor pretend to know but..One way around it is only buy cartons of Red Beef, if your supplier can’t garrantee its won’t be dark, change suppliers. As soon as you start cancelling orders, because of dark cutting, I would presume suppliers usually toe the line. We can put man on the moon, design bombs that can wipe out whole cities, but can’t control what food we produce…..?

I have been a butcher for many years and have always noticed dark cutting grass fed beef we buy in cartons from wholesalers in autum. We have always put it down to heat wave conditions at time of slaughter. I hope now with more research they can rectify the problem. One question I have is why meat works still process dark cutting beef because it is a huge lost to retail butchers?

Interesting piece. The prevailing theory at the UK meatworks where I was based was that a sudden drop in ambient air temperatures in autumn, rather than longer term nutritional factors, led to lower glycogen levels. We felt that a sudden cold snap of weather in the autumn often triggered a spike in dark cutting carcases, perhaps because cattle were using more energy to keep warm at night.