It has been dubbed by opponents as a ‘disease of regulation’, a case of the cure being worse than the cause, where strict eradication policies often inflict greater pain on affected properties than the target disease itself.

At the same time advocates of existing Johne’s management policies, which include high impact control measures in some States, argue “throwing open the gates” and deregulating Johne’s management would unnecessarily expose all Australian cattle producers to potentially greater on-farm costs and trade impacts.

People on all sides of the Johne’s management debate will get an opportunity to argue their case before an independent chair early next year when a major national review of the national BJD program takes place.

Those in favour

Arguments in favour of eradicating Johne’s Disease tend to focus largely on the potential costs all producers in Australia could face if Australia was to “de-regulate” Johne’s Disease management.

AgForce Queensland says it is well aware of the financial and emotional strain that has been placed on Johne’s affected producers since the detection of Johne’s Disease at the Rockley Stud in Central Queensland in November 2012.

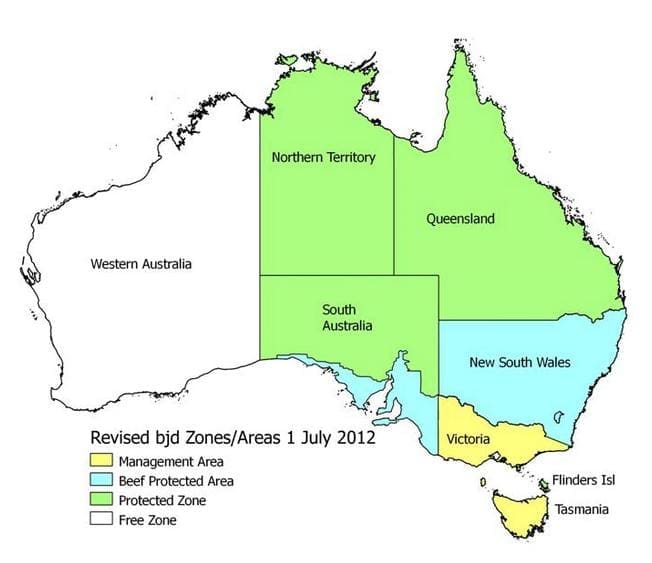

However, as an advocacy group that represents the cattle industry in its entirety, it says Queensland remaining as a BJD Protected Zone is vital for the long term profitability of the sector as a whole.

In a previous Beef Central article AgForce spelled out some of the reasons why it believes the existing control and eradication approach is in the best interests of the Queensland beef and cattle industry, an extract of which includes:

- Animal Health and Welfare Outcomes: “This is an often ignored factor. BJD is a disease and, as such, has an adverse impact on the health of an animal. As producers we have a legal duty of care to look after our livestock to the best of our ability and to sell animals that are fit for purpose. Furthermore, why would producers want to contend with another disease which has potential to affect their operation, particularly one that cannot yet be effectively prevented or clinically treated?”

- Trade/Market Access: “While it has been claimed this argument has been ‘oversold’ the threat of diminished market access is very real. Internationally, there are 134 technical trade barriers related to BJD in 43 markets for feeder, breeder and genetic exports.”

- Lack of Research and Development: “Research and Development work aimed at investigating BJD in a northern pastoral context is in its infancy with considerable work ahead before any results can be collected and conclusions made. At this point, we know nothing about how BJD survives, thrives or dies in the diverse regions and seasons across Queensland. Until hard evidence is readily available to industry, the Protected Zone approach best positioned to reduce risk throughout the supply chain.”

- Links to human health or consumption: “This is perhaps the elephant in the room. It has been widely reported BJD is not a disease that affects meat consumption or human health. This being said, scientific research continues to attempt to seek out links between Johne’s disease and Crohn’s disease. As an industry, we should be ever hopeful that this is not the case however this perception does exist and scientists are working hard to correlate the links between the two. Given increasing consumer scrutiny this is another critical reason why BJD should be managed to the lowest common denominator in Queensland.”

- Reviews of the alternatives: “There have been frequent calls to adopt an alternative management approach such as ‘deregulated’ or ‘producer managed’ or to adopt an interstate model. Factors to consider include but are not restricted to the impact on buyers or BJD free producers; the impact on BJD quarantined producers and the costs passed back to industry, with producers having to pay to participate in market assurance programs, testing, vets fees and compliance programs which they do not currently pay under the current regime.”

Supporters of the existing system further argue that despite claims to the contrary JD does have an impact on production and does have an impact on trade (see list of importing countries that impose a requirement around Johne’s Disease). Also, they add, trade is not just about international trade but interstate and intrastate (i.e. property to property) trade, making ‘trade’ an important consideration in determining the control program.

Those against

Arguments in favour of ‘de-regulating’ the disease and allowing producers to manage it at farm level with the use of vaccinations where required tend to focus on the heavy impacts caused to producers affected by quarantine programs, and the evidence that suggests Johne’s is a disease of minimal consequence to herd productivity or trade.

Opponents of the existing national policy dismiss suggestions that Australia must remain free of Johne’s Disease to protect its access to export markets.

BJD is already endemic in nearly every other country, they point out, including all of Australia’s major export markets. Under World Trade Organisation rules it is illegal to impose a trading restriction for a disease present in the importing country.

In terms of live export markets, they point to the tens of thousands of Australian dairy heifers already exported to China and Japan each year, even though JD is endemic in the Australian dairy herd.

Additionally, they state that no conclusive link has been found between JD and Crohn’s Disease despite this having been investigated for more than 100 years. If a link between JD and Crohn’s Disease was still to be established, it would seem likely that any link would be a very weak one, given that 100 years of research has still not been able to establish a conclusive link.

‘Attempting to eradicate Johne’s is akin to attempting to eradicate the common cold’

The eradication of Johne’s is also an impossible goal, they contend. “Attempting to eradicate Johne’s Disease from Australia’s bovine population is akin to attempting to eradicate the common cold from the human population,” says BJD action group spokesperson and Australian Beef Industry Foundation chair John Gunthorpe.

“BJD cannot be eradicated,” he says. “Many nations have tried and failed. There are many diseases worse than BJD inflicting greater damage on the beef industry than BJD and these are managed on farm.”

An economic analysis by QDAFF economist Fred Chudleigh performed last year and released in January also added weight to claims Johne’s is a disease of minimal production impact.

The report estimated that annual losses in an infected beef herd of 575 cows would total just $259 per year.

The same analysis further suggested that if 5pc of all Queensland cattle herds became infected with BJD by 2043, the annual cost to industry would be $258,000 per year.

“We support entrusting the management of the disease to cattle producers in the same way we do many other diseases and many of those are far more dangerous and costly than BJD,” Mr Gunthorpe said.

More than a case of regulate or deregulate

One senior industry spokesperson said this week it was too simplistic to state that the disease could be either “regulated” or “deregulated”.

“It’s a case of having a program that provides the tools needed by producers who want to prove their herds are clear of JD and who want to maintain their herd’s status,” the spokesperson said.

“This may differ from region to region. Many of those opposed to the current program simply want the gates opened, but there is a silent majority who would and should be concerned about such an approach.”

Further details on the contrasting positions of Cattle Council of Australia and the Australian Registered Cattle Breeders Association on Johne’s management can be viewed in this earlier Beef Central article.

Affected producers taking the hit for industry

Regardless of where you sit on the debate, one point that few seem to dispute is that those producers who are asked to shoulder the burden of protecting the broader industry from the disease should be entitled to adequate compensation.

While debate has raged for and against eradication in Queensland over the past two years, dozens of family farming businesses in the State have been pushed to the brink of financial and emotional devastation through no direct fault of their own during that time.

Most remain largely uncompensated for their losses, which were effectively incurred to protect other producers from the disease.

Rockley Brahman Stud principal Ashley Kirk said two years of quarantine and woefully inadequate compensation has had a devastating impact on his family and his family’s business.

As someone who has borne the brunt of the industry’s desire to remain protected from Johne’s, there is no question in his mind that the current policy is flawed and should be replaced by a system that allows producers to manage the disease on-farm, as is already done with other notifiable diseases such as Pestivirus and Leptospirosos.

In a written statement supplied to Beef Central Mr Kirk said he believes the Queensland Government had two clear options:

“Change the flawed policy and have no future compensation for producers, or retain the policy and fully compensate producers.

“I am certain that producers would not want to contribute to a biosecurity fund that will be of little benefit to them when they actually wish to make a claim.

‘We strongly believe that all those affected should be fully compensated’

“We strongly believe that all those affected should be fully compensated for their losses.”

He said affected producers were still waiting for the Newman Government to make good on its statement in January 2013 that “the Newman Government does not expect individual producers to bear the cost of eradication programs that ultimately benefit all of the cattle industry”. He said he was also astonished that industry bodies such as Agforce were failing to push for full compensation for affected producers.

As mentioned earlier, a major national review of BJD policy which has been brought forward to February 2015 will provide a forum for all interested parties to argue their case.

Representatives of producers affected by the BJD control program in Queensland will also meet with Queensland Agriculture Minister John McVeigh in Brisbane tomorrow to argue their case for deregulation of the disease.

Tony please provide your source as this is news to me and I have read extensively on this issue.

The link between MAP and Crohn’s is not hypothical: it is REAL. The sooner the dairy and beef industry will accept this fact the better we will find ways to control BJD. The technology exists to detect and control the spread of the bacterium in dairies!!

How many cattle die in Queensland from snake bite, dogs , lightning strike, AND DROUGHT?

How many die from BJD?

Can the disease even survive west of the Great Dividing Range in Queensland?