THE Australian beef industry stands to benefit greatly from an inevitable decline in US beef production next year, a Casino seminar audience has heard.

Local beef processor Simon Stahl from Casino Food Group, industry analyst Matt Dalgleish from Episode 3 and NSW lotfeeder Andrew Talbot from Elders Killara stepped through some of the ‘headwinds and tailwinds’ they see affecting cattle and meat prices heading into 2023 during a Beef Central seminar at Primex Field days on Friday. Most of Mr Talbot’s comment were published in this item yesterday

Matt Dalgleish

Matt Dalgleish highlighted the stark contrast between Australian and US beef industries at present in terms of the drought and recovery cycle.

Driven by back-to-back great seasons, Australia was seeing strong herd recovery (around 6pc annually) over the past two years. That had produced the lowest female slaughter ratio (the percentage of females in the overall kill) seen in 30 years this year, as females are retained for breeding.

Meanwhile the US was currently at the complete opposite end of the spectrum in terms of female slaughter – in their third year of a liquidation phase due to drought, producing the highest female slaughter ratio since records started in 1986.

“If you look across the historic records, the average destocking phase in the US takes around four and a half years, and the rebuild phase around five-and-a-half. So the whole cycle usually is around a decade,” Mr Dalgleish said.

This suggested the US was likely to be in liquidation for at least another one, if not two years.

“That’s important for Australian beef, because of the number of markets we share,” he said.

“US cattle prices tend to drive the global market, and our prices tend to follow that US trend, over the longer term.”

Data suggested the back-end of the US herd liquidation phase is almost always associated with higher livestock pricing.

“It makes sense,” Mr Dalgleish said. “They are reducing the supply of animals, and they get to the stage where they don’t have enough slaughter cattle, and cattle prices go up. That’s telling us that in the next few years, that US cattle price will continue to build, which in turn will support the global cattle price (including Australia).”

In contrast, Australia was now in the third year of a La Nina cycle – only the fourth time this has happened in a hundred years. Given that patterns between wet and dry seasons normally had a gap of two years, it meant that Australia could see a dry period somewhere around the middle of this decade, Mr Dalgleish suggested.

While that could lead to some downwards cattle price pressure, the benefit was that it could coincide with the last bit of US liquidation phase, supporting international prices.

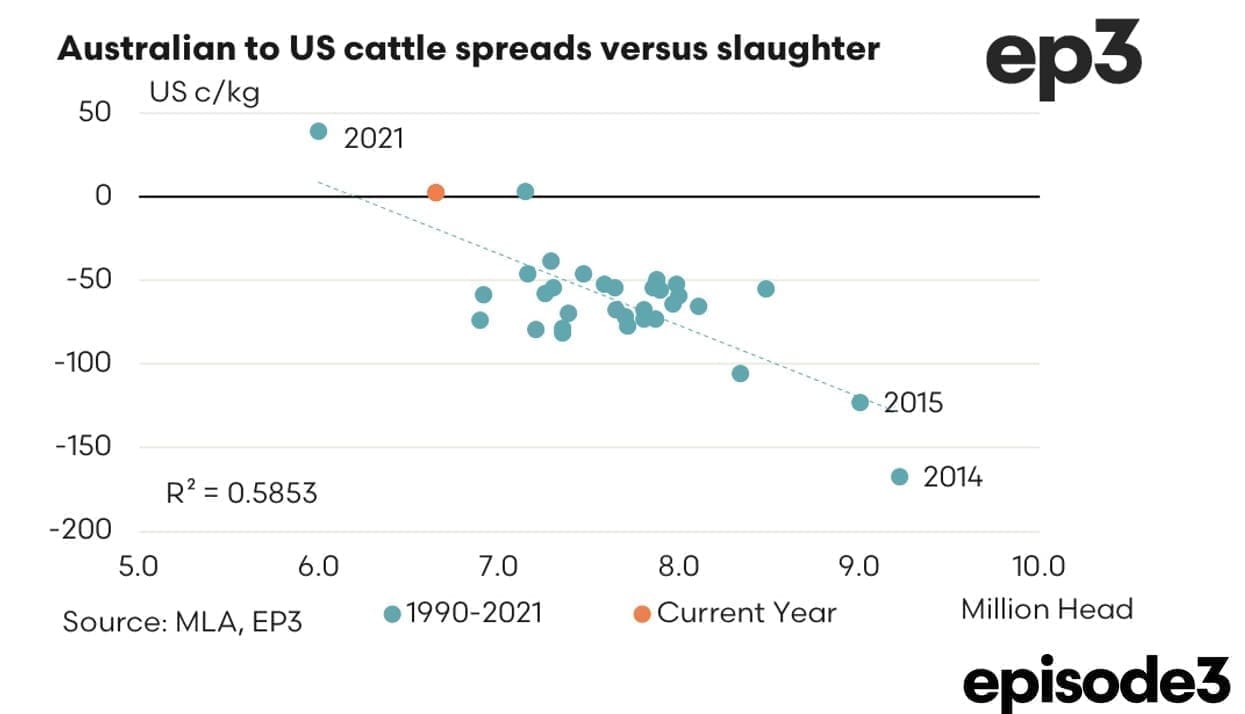

The graph below was presented to illustrate the recent relationship between cattle prices in Australia and the US. The annual rates of Australian kill are presented across the Y (horizontal) axis, with percentages above, or below the US cattle price (in US$ terms) across the X axis, for Australian heavy steers.

It shows the current year line-ball with US cattle price, in US$ equivalent terms (across the zero line), while last year the Aussie steer price (due to extremely low rates of kill around 6m head) was about 40c/kg better off. All other years since 1990 show a discount (bunched around 50c/kg), including the extreme 2014-15 years when Australia was killing extremely high numbers due to drought. That pushed the discount on Australian cattle to as much as 150c/kg.

“As Australia’s national kill starts to climb again next year, as a result of recent herd rebuilding, we are going to see some of that price difference again emerge, with a greater discount against US steers,” Mr Dalgleish said. “At this current point, the discount is now about 7pc below US rates, and trending down, which is the more normal scenario.”

In summary, he is forecasting a little pressure on Australian slaughter cattle pricing – but not a significant or dramatic collapse.

“We’re talking a heavy steer going from somewhere around 450c/kg liveweight now (around 790c/kg carcase weight, reflecting of pricing further south, rather than Queensland) to the high 300’s, between now and late 2023,” Mr Dalgleish said.

Processing labour challenge could directly influence livestock prices

Also speaking at the Primex seminar was the Northern Cooperative Meat Co’s chief executive officer Simon Stahl.

Simon Stahl

The implications in the current widespread US drought represented an ‘enormous story’ for Australian beef’s prospects going forward, he said.

“They (US producers) are now feeling the same pain that we did in 2019-20,” Mr Stahl said.

The US was a very big beef producer, but they consumed 90 percent of the product themselves, typically exporting only 10pc of their production. Currently that export figure was 15pc due to drought turnoff, with heavy exports into markets like Korea, Japan and China.

“But they will lose that capacity at some stage – when it does finally rain,” Mr Stahl said.

“The US will rapidly move out of export, which represents a huge opportunity for Australia, given we compete head to head with the US in many key markets.”

He said if you were to take a cynical view, the inevitable decline in supply out of the US next year could add momentum in China’s willingness to deal more openly with Australia for beef imports.

“But reduced US supply will definitely allow Australia to get a better foothold in the big markets like Korea and Japan again, where we have lost some ground due to low kills,” he said.

Huge labour challenge emerging

Northern Cooperative Meat Co (Casino Food Coop) last week filed its annual result, recording a sizeable $8.9 million loss for the year. That largely reflected the low levels of throughput through the plant last financial year.

Mr Stahl said slaughter activity in Australia was still at the bottom of the cycle due to herd rebuilding and the effects of earlier drought, with adult slaughter this year forecast at around six million head. That’s down from nine million during the earlier drought period, and a long-term average around 7.5 million.

“There’s wide expectation of some increase next year, as we continue rebuilding the herd, before getting into more normal numbers by 2024.

Price movements

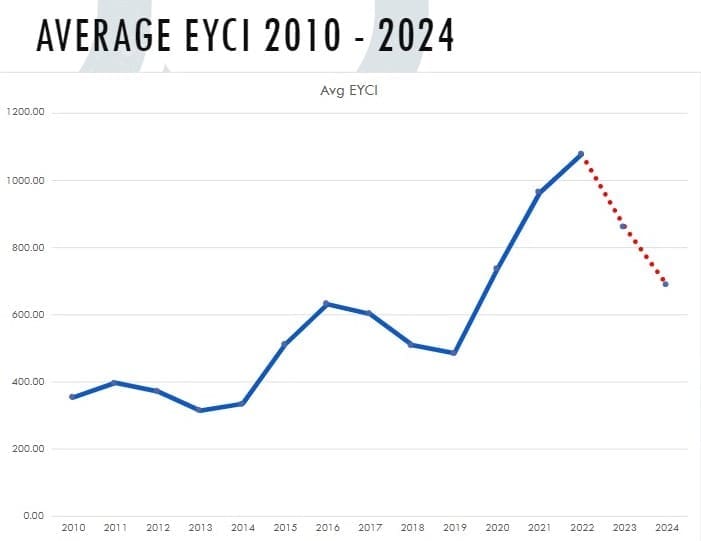

Following a deep, but short-lived slump in August, when concerns about FMD and LSD disease risk from Indonesia reached their peak, the Eastern Young Cattle Indicator had shot higher again during September, before settling where it is today at a little of 1000c.

Mr Stahl told the audience he agreed with the widely held view that livestock prices would now correct, from the extreme levels they reached earlier this year.

“They were unsustainable at those earlier levels,” he said. “It’s not because we (processors) made a decision to go and pay less for those same cattle – it’s simple supply and demand,” he said.

“At some stage they do have to correct, and we think it is going to be next year. We think the young cattle market could fall 20 percent, meaning somewhere in the 900c/kg range on the Eastern Young Cattle Indicator next year, before falling into the 700s in 2024, as the herd keeps rebuilding, and pressure (see references below) grows on the processing sector.”

Labour challenge

Mr Stahl said the big challenge on the horizon was the labour skills shortage – whether it be farming, processing, or the local cafe.

“That’s the big pinch point for next year,” he said.

“Slaughter cattle supply will increase in 2023, certainly, but labour stands to be the big pinch-point influencing cattle price next year. If we get any sort of over-run in supply next year – even a short dry period – it is going to start backing cattle up at meatworks.

“Everyone knows Dinmore, the biggest beef plant in Australia, closed its second daily shift when the supply shortage set in during herd rebuilding, representing 8000 cattle a week, and employing 600 people.

“They won’t get that second shift re-started, in my opinion – even if cattle supply warrants it. There’s no longer the access to that sort of labour, let alone skilled labour.”

Headwinds

Matt Dalgleish said even with the decline in export competition out of the US next year, there was still more headwinds than tailwinds for Australia in export markets.

“I’m not talking a crash in pricing, so much as a steady decline in the next few years,” he said.

“As US supply declines after the drought finishes, their meat price will inevitably rise, making Australian beef more competitive.

But America would inevitably try to hold onto as much of the export gains they have made over the past year or so, lotfeeder Andrew Talbot told the audience.

“But what that will mean is a shortfall of manufacturing type product (grinding beef) for the US customers, and I have no doubt that could well come from places like Australia,” Mr Talbot said.

A seminar participant asked who (along the supply chain) was making the profit margin back in the drought, when cattle prices were lower.

Mr Talbot said people should not assume that the meat sales price processors were getting during the 2019-20 drought years, when cattle were cheaper, was as high as it is today.

“One of our recent supermarket contact prices was $10.80/kg, but three years ago during drought, it was around $6.50. The margins in the feedlot and processing game have not changed a whole lot in the last ten years. What changes is how much revenue you need to make that margin,” he said.

“Don’t think for a moment that when cattle process are lower, that everyone else is making money at the producers’ expense. They weren’t. The difficult is that there is only a certain amount of money to be made across the beef chain, at any given time.”