THE unfolding emergency in the Ukraine has deep implications for a heavily trade-exposed Australia, which is torn between powerful friends and grappling with the challenges of a post-COVID world.

This emergency is the tip of a geopolitical iceberg that has long-term ramifications for our nation and our agriculture and agrifood sector, which is a foundation of the Australian economy and is key to our post-COVID economic recovery.

The increasing alliance between Russia and one of our most valuable trading partners, China, is resulting in the rebalancing of power and influence from West to East. We are perhaps bearing witness to the single biggest re-distribution of power and geopolitical influence since the Second World War. The West’s economic sanctions activity against Russia in response to the Ukraine emergency brings this alliance into laser focus.

Australian agriculture has fared well throughout the pandemic, with a record forecast gross value of $78 billion in 2021-22. The sector has overcome a great deal to achieve that result, but new challenges exist with the cost of key inputs like fuel, fertiliser, labour, and equipment all increasing. Fertiliser alone has skyrocketed with a 74 percent increase in the cost of urea from 2020 to 2021 and a 102pc increase for monoammonium phosphate (MAP) in the same period.

Supply chain disruption and trade volatility has had tangible impacts on farmers from lobster producers, wine grape and grain growers facing market closures, chemical shortages and increasing input costs. The digital disruption of JBS, the largest meat processor in the Southern Hemisphere, COVID furloughs and livestock processors haemorrhaging money through shutdowns have been a feature. Our response, and the actions we have taken to diversify, to become more resilient and regionally self-reliant, will be crucial as China and Russia deepen their economic and security cooperation. What we have experienced to date could be a precursor of what’s around the corner.

In 2020 Russia was Australia’s 48th largest trading partner, China is our biggest two-way trading partner. Thomas Elder Markets highlights that Australia is strategically less directly reliant on Russia with trade inflows and outflows accounting for 0.1pc and 0.2pc of our total trade respectively. It’s Russia’s deepening relationship with China, who accounts for 31pc of our trade with the world that catches our attention.

In 2020 Russia was Australia’s 48th largest trading partner, China is our biggest two-way trading partner. Thomas Elder Markets highlights that Australia is strategically less directly reliant on Russia with trade inflows and outflows accounting for 0.1pc and 0.2pc of our total trade respectively. It’s Russia’s deepening relationship with China, who accounts for 31pc of our trade with the world that catches our attention.

In December, President Xi of China stated during a video call with Russia’s President Putin that their countries are “setting an example of a new type of international relations and the community, of a common destiny for humanity.” In turn, President Putin exclaimed that “Russia and China’s close co-ordination in the world arena, and their responsible joint approach to current global problems have become a significant factor of stability in international relations.”

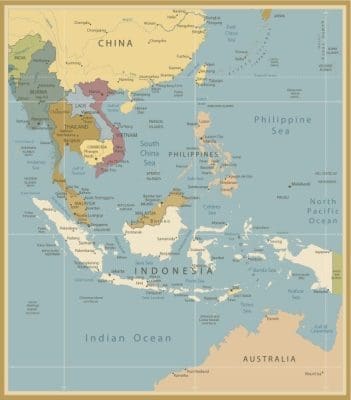

This combined vision of a ‘new type of international relations’ poses a clear threat to the liberal, rules-based world order that Australia’s agricultural trade has thrived under. This compounds China’s increasing influence in our region which has clear implications for the agriculture sectors capacity to import key inputs, and export what we produce. Thomas Shugart highlights that risk in his recent Lowy Institute analyses; “In fact, the PLA (China’s People’s Liberation Army) is on track to gain the ability to threaten Australia’s access to international markets and energy sources and thus obtain direct coercive power over Australia’s economic wellbeing.”

Despite the national security rhetoric of the last fortnight, the Prime Minister has stated that we must strive for peaceful coexistence.

Despite the national security rhetoric of the last fortnight, the Prime Minister has stated that we must strive for peaceful coexistence.

It is true that we must hope for continued mutually beneficial trade relationships while protecting our sovereignty and playing our part in feeding and clothing the world.

But our trade exposed agriculture and agrifood sector must prepare for increased disruption and volatility.

Since the onset of the pandemic, we have initiated trade diversification programs and returned greater focus to our region but this redistribution of power from West to East prompts several questions, including:

Have we done enough to diversify, become more resilient, and do our ties with our nearest neighbours have enough depth for Australia to be regionally self-reliant?

Are our digital systems cyber resilient? Are individual agribusinesses and exporters prepared to pivot quickly, how much exposure do businesses have to a single supplier or customer?

Economic sanctions are being ramped up by the West against Russia every day and if successful, Russia will temper its posture and the world will find an uneasy balance, for now.

But if economic sanctions don’t work, I see two options:

1. Russia continues to carry out its territorial ambitions in Eastern Europe, China is emboldened – the US and its allies back down and a new era dawns with China and Russia sharing more dominant influence in a new world order; or,

2. The US and its allies hold the line and engage Russia militarily, which likely leads to conflict, and potentially conflict with China.

Both scenarios where sanctions fail are bad for Australia. The first presents a reality that will challenge our sovereignty and the right to our own self-determination.

The conditions that our agriculture and agrifood sector have thrived under will be redefined and how we do business will be informed by the degree to which we are allowed to determine our own role in international trade.

From the second, I cannot see anything other than chaos.

These themes are big and seem far away, but they are acutely relevant to all of us involved in agriculture because we export 70pc of what we produce. While we hope that economic sanctions work, tensions ease and peaceful diplomatic relations prevail, we need to redouble our efforts in preparing for the alternative. We need to increase efforts to build the resilience and efficiency of our agriculture and agrifood supply chains and digital systems. We need to increase our efforts to diversify market access and spread risk for exporters. We need to build on our focus of becoming regionally self-reliant and work to ensure that our key strategic inputs are not unduly exposed.

Australia’s influence in the Ukraine emergency may be minimal, and even less so on the broader rebalancing of power, but the impacts on Australian farmers, food processors and exporters are clear. So too is the narrative from the Australian government, Australia’s sovereignty is not negotiable, and nor should it be. It is sadly reasonable then to expect that we will see an increase in activities aimed at disruption and coercion, and agriculture is one fundamental means by which that aim can be achieved.

Victor Frankl said that when we can no longer change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves. For Australian agriculture that challenge is upon us.

- Andrew Henderson is the founder and principal of Agsecure and Agsecure Investment and chair of the SAFEMEAT Advisory Group.

Related articles by same author:

Biosecurity = food security = national security – July 2021

The case for Australia to pursue ‘Regional Self-Reliance’ – Sep 2020