A NUMBER of Senate inquiries into the meat supply chain and in particular the beef supply chain recommended tools to improve transparency beyond the farm gate need to be developed for the Australian situation.

To date, there is no regular reporting that might be said to fulfill these recommendations.

In 2013, the Australian Beef Association together with the University of Tasmania performed an analysis whereby beef carcases were broken down to retail beef items in order to determine the yield of each from a beef carcase.

They then developed a spreadsheet to calculate what proportion of the retail value that came back to livestock producers.

The model was a little complicated in that assumptions had to be made on the cost of killing, value of by-products that was credited to processors, cost of boning and packing into wholesale or boxed beef cuts and the cost of packaging and preparation of final items for retail sale.

At that time, the majority of fresh beef was prepared in the major retail stores from boxed meat although there was a trend for more products on offer to be brought-in, shelf ready, from centralised packaging facilities.

Since then, almost all supermarkets have eliminated their in-store butcher shops, so product now offered to consumers is almost exclusively brought in shelf ready having been cut, trimmed, packaged and priced at a central location.

This was discussed in a previous opinion piece of mine that was published on Beef Central on July 4. The article created some considerable discussion and feedback from readers.

That article asserted that the supermarket oligopoly had pushed costs down the supply chain. That they had significantly reduced their own costs by eliminating the need for skilled butchers and specialised cleaning teams in store, reduced wastage and discounts to clear, converted valuable store space from meat preparation to retail shelf area and improved efficiency and reduced costs in a number of related areas.

It further suggested that as a consequence, the supermarkets had increased their share of the meat retail spend at the expense of those down the chain including producers.

Looking back at the data collected in 2013, and eliminating the assumptions on costs, credits, further processing, instore costs that we have little visibility to, we estimated that producers received some 40.7pc of retail spend, less the cost of sale (cost of transport to place of purchase, agents commissions, saleyard fees and transaction levy) which could be as much as 8pc of sale price.

The difference between the red and the green supermarket chains was negligible. The cost of taking a beast from farm gate point-of-sale to the retail customer was calculated to be $1730.

Same exercise in 2023

The same exercise was undertaken for 2023, showing producers receiving 38.5pc less costs of sale, but that the cost of taking the same beast from the farmgate to the consumer was now more than $3000. The retail prices collected were conservative, in that the lowest price for each item was used.

For instance a silverside could be offered as a corned silverside at $10 per kg or as a “sizzle steak” at a much higher price and the lower prices were used in the model. Again, the red and green retailers had large numbers of their items priced identically.

Jonathen Barrett, senior business journalist for The Guardian, recently wrote, “Coles and Woolworths have consistently expanded their profit margins in a cost-of-living crisis, outstripping their UK counterparts*”, and he identified the lack of competition as the main cause (*The Guardian 27 July 2023).

Alan Fels when commenting on the PWC consulting issue and the competition in that sector stated, “They have a similar culture which means they don’t really compete, the four look alike and their competition is quite marginal*” (*Professor Alan Fels interview, ABC radio, 17/7/2023 5;06pm).

With only two major supermarkets in the space and some minor ones, the concentration in the retail sector is even more pronounced, and yes, they have a similar ‘culture’, as Prof Fels would say.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics collects price information on a range of consumer products including beef and lamb under the categories “Beef and Veal” and “Lamb and Goat” respectively. This data were released last week and showed that Beef and Veal prices at retail eased o.2pc in February and 0.4pc in each March and April and that for the period April 2022-April 2023, the decline had been a mere 0.8pc. The situation for Lamb was similar.

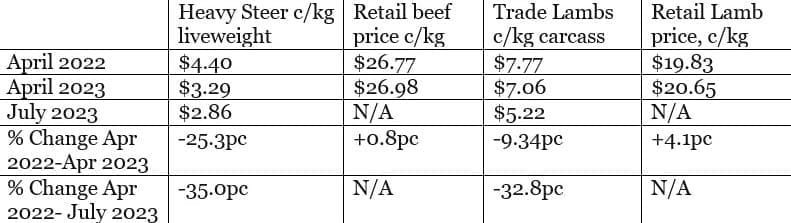

MLA’s own indicator prices show similar trends:

Whilst livestock prices have been in freefall over recent times, all evidence suggests that retail prices on beef and lamb have hardly moved. It could not be said that the supermarkets have shown any leadership or corporate social responsibility in fighting inflation and supporting consumers with lower prices, in fact it would appear quite the opposite, that they have used their market power to increase their profits.

It took a Royal Commission to get the big four Banks to behave, perhaps that is what is now need in the retail sector.

Transparency and regular reporting beyond the farm gate in beef and lamb supply chains is sorely needed.

* Author, Andrew Dunlop, has spent 40 years in the meat and livestock industries including two tours of duty to Japan totaling 15 years. As well as Batchelors and a Masters Degrees in Animal Sciences (University of Sydney), he was awarded a post graduate fellowship with the Science and Technology Agency of Japan where he spent two years with Japan’s National Meat Research Institute in Shimane Prefecture, the home of Wagyu Meat Science and of Wagyu breeding. He held senior positions with meat exporters out of Australia, Meat Business Managers positions with national retailers and with a Japanese meat importer in Japan. Now semi retired, he continues to own and run a beef cattle operation on the Monaro in southern NSW.