Producers of laboratory-cultured animal cells for food needs to come up with a description other than ‘meat’, argues Australian Farm Institute’s Mick Keogh

SO-CALLED ‘clean meat’ is the latest darling of the stock market in the US, with major investors putting their money into start-ups like Impossible Foods, Hampton Creek, and MosaMeat.

Quite a few commentators and activists have claimed that these developments in alternative proteins signal the end of animal agriculture as we know it, citing ‘significant advantages’ in environmental and animal welfare outcomes as key reasons for the transition.

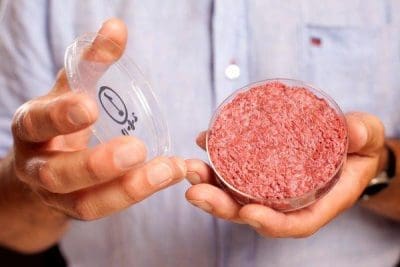

Lab-grown meat burger

Two issues arising from the development of ‘clean meat’ need careful consideration. The first may seem trivial but in fact is of major importance: that is what these products are called. The second, equally important, is whether they can justify claims to be more environmentally friendly than the foods they aim to replace.

Meat is a term that has long-established meaning, whether considered formally via dictionary definitions, or – more importantly – in the minds of consumers. The Oxford Dictionary states that meat means the flesh of an animal, typically a mammal or bird, as food. Clearly, a chemically reconstituted artificial protein that has been produced in a factory utilising multiple chemical additives, some of which are derived from genetically modified animal and plant matter, does not in any way fit the above definitions. Therefore, it is quite incorrect to use the term ‘meat’ as a name for these products.

The issue of cultured or ‘lab grown’ meat is slightly different, in that it is derived from animal cells multiplied via culturing in a laboratory. It could be argued that these products can be described as ‘meat’, although consumers may be somewhat surprised if they were provided with the complete details of how these products are created.

Leaving cultured meat aside, the use of the term ‘meat’ to describe chemically reconstituted artificial protein is not only misleading but is also an attempt to appropriate the value that consumers attribute to products referred to as meat – and are prepared to pay for – to create a market for these new products.

The importance of food terminology and names has been highlighted in the past, with the names of wine regions in France being a classic example. The European Commission moved to enact Geographical Indicator regulations some time ago, to protect wine producers in regions like Champagne and Burgundy from having their brand equity eroded through the use of these terms to describe wine from other regions.

“There is a very strong argument that livestock producers and meat processors should have available similar protection”

The EC maintains that naming things correctly “matters economically and culturally”. There is a very strong argument that livestock producers and meat processors should have available similar protection, something which is currently a subject of debate in the USA.

The second issue of dispute is whether these products can justify the claim that they are somehow environmentally ‘cleaner’ than actual meat.

The websites of some of these companies are littered with claims about the environmental damage associated with conventional livestock production, but many of the so-called facts they cite are at best contentious, and at worst blatantly and obviously incorrect.

The following quotes from the website of Impossible Foods (manufacturer of an entirely plant-based hamburger pattie) are classic examples:

- Because we use 0% cows, the Impossible Burger uses a fraction of the Earth’s natural resources. Compared to cows, the Impossible Burger uses 95% less land, 74% less water, and creates 87% less greenhouse gas emissions.

- The way the world produces meat today is taking an enormous toll on our planet. According to livestock researchers, animal agriculture uses 30% of all land, over 25% of all freshwater on Earth, and creates as much greenhouse gas emissions as all of the world’s cars, trucks, trains, ships, and airplanes combined.

These claims are not referenced to any authoritative research and appear to rely on some heavily criticised life cycle assessments published some time ago which contained fundamental errors.

Much mis-quoted water use

One example was the much quoted “200,000 litres of water to produce one kilo of beef”. This and other similarly outlandish figures were arrived at by making patently incorrect assumptions, such as that all the rain that falls on pastures being grazed by cattle should be attributed to those cattle, and any runoff, deep soil drainage or evaporation simply ignored! Detailed, objective life cycle assessment of Australian beef cattle production systems has identified that actual water use ranges between 100 and 300 litres per kilogram liveweight, equal to between 200 and 600 litres per kilogram of meat. Exactly what objective data Impossible Foods has utilised to make the above claim is unknown, but it seems to be highly misleading.

Similar criticisms apply to the comparison of livestock and transport emissions. The above appears to be based on a heavily criticised United Nations report released in 2006 entitled “Livestock’s Long Shadow”. This report compared greenhouse gas emissions estimated for a very broadly defined livestock sector (including land clearing, fertiliser, farm, feed, transport and processing) with just the emissions arising from fuel use in transport, ignoring all the emissions associated with vehicle manufacturing, tyres, and the construction and maintenance of roads, bridges, railways and airports. This was blatantly an “apples vs oranges” comparison, which one of the report’s authors conceded in 2010.

In the end it is up to consumers to decide whether they prefer meat or non-conventional meat substitutes, but they should at the very least be presented with objective information to enable informed decision making, and this includes the naming of these products.

Therein lies a problem. The use of the term ‘clean meat’ is obviously misleading on both counts, as the products have questionable ‘clean’ credentials and are very obviously not meat.

Exactly what chemically reconstituted artificial proteins should be called is yet to be agreed – but perhaps somebody will eventually come up with an acronym!

- See James Nason’s earlier treatment of this topic here.