NINETY percent of producer complaints about grading performance in beef plants could be attributed to misunderstandings about how processor price grids worked, the Senate Inquiry into the red meat processing sector was told yesterday.

AusMeat, and more specifically, its Industry Language and Standards committee, have come under sustained criticism both from senate committee members and producers giving testimony at inquiry hearing sessions in Albury yesterday, and Canberra last week.

AusMeat chief executive Ian King was questioned in depth during yesterday’s Albury session, which attracted an unusually large grassroots producer audience.

AusMeat chief executive Ian King was questioned in depth during yesterday’s Albury session, which attracted an unusually large grassroots producer audience.

Topics ranged from producer representation on the AusMeat board to dispute resolution over apparent misgrading of carcases, to pressure on graders to grade according to company requirements.

Sen Bridget Mackenzie asked Mr King whether he appreciated and accepted the “severe lack of confidence” that the senate inquiry had detected from across the supply chain in regards to meatworks grading performance.

“I certainly hear the message,” he said.

“In terms of the credibility of those messages, I struggle with it however, because we do not get the evidence; we have not got concrete evidence; and from my position as an industry co-regulator, on behalf of government, I do need evidence (to act).”

“Whenever we have followed up on claims, we’ve tended to find it is based on hearsay, as opposed to reality. But I have every confidence that the grading system is performing well,” Mr King said.

“That is not what we are hearing, Mr King, and we are hearing from processors and producer alike that there are people who have an issue with how their cattle have been graded,” Sen Mackenzie said.

“For a variety of reasons, they have not raised it,” she said.

Misunderstanding about grids

Quite often, however, such complaints were not to do with grading performance, Ian King suggested, but with misunderstanding about how processor price grids operated.

“This is the challenge for industry, in my opinion,” he said.

“In general, producers do not understand feedback sheets; they do not fully understand grading.”

“The industry has been driven by commodity pricing for such a long time that now that we are moving into this value-based marketing area, there is a questionmark being raised over some of the grid penalties being applied,” he said.

“Earlier in today’s hearing, a producer gave evidence about ‘not getting the right amount of money and being really heavily penalised’ by their processor. But if you understand the structure of the price grids, there are indeed heavy penalties in places for cattle that do not meet the company’s specifications,” Mr King said.

“In the old days, if a producer sent 20 head of cattle in, they got the average price across all 20 head. Today, they send in 20, and get priced accordingly on 18 really good ones, and discounted on the other two that do not perform so well.”

“In that situation, guess who gets the blame? It’s the grader, or somebody else. Or the argument is put that it couldn’t be right, because the other 18 steers in the mob all made the top price.”

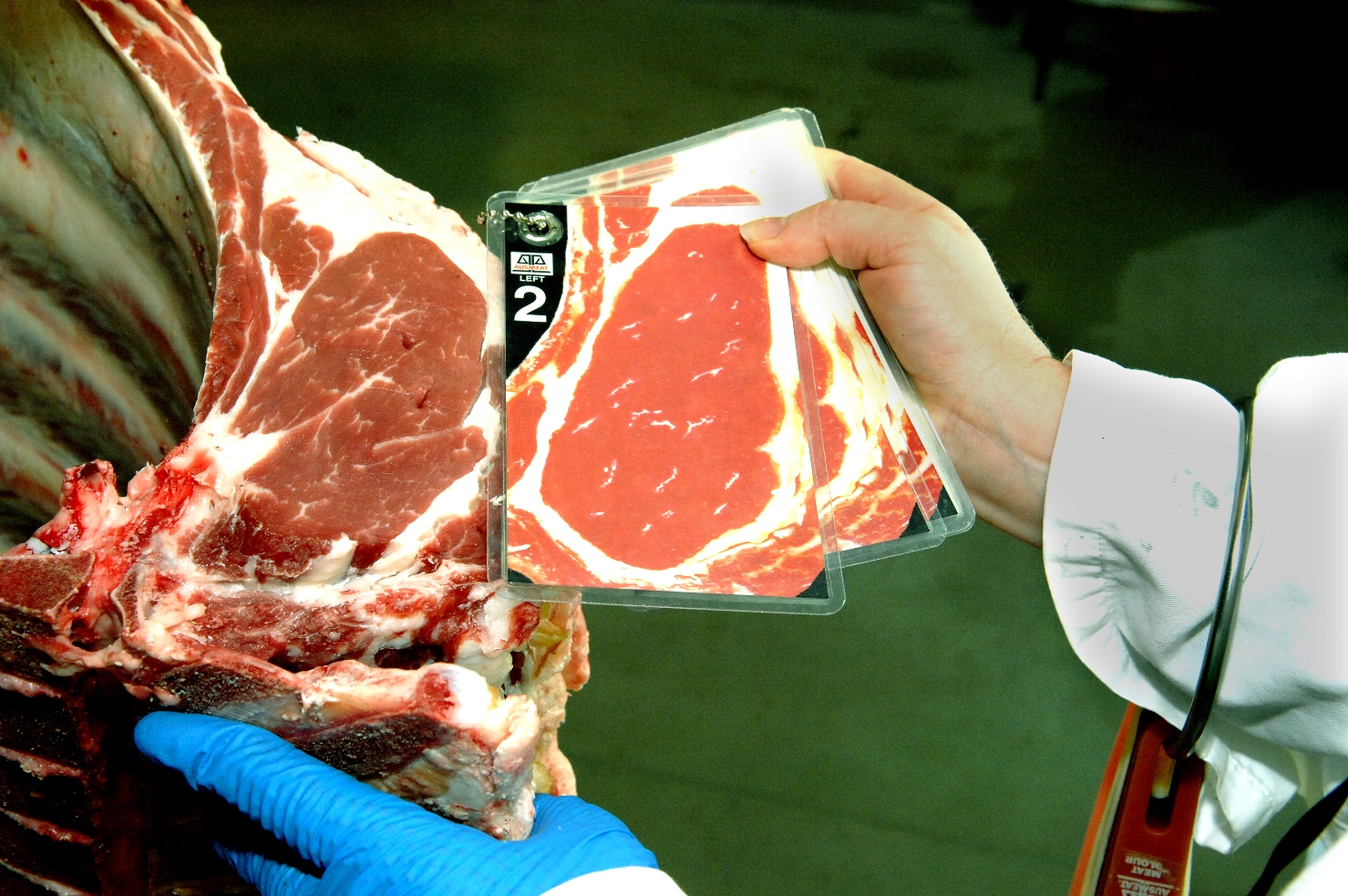

Mr King said it was ‘music to his ears’ to hear Dr Alex Ball talk in earlier testimony about the future of objective grading using new technologies, designed to reduce or remove current subjectivity from the grading process.

“Burt we have to realistic about it: producers are going to continue to be penalised for those cattle and carcases that do not meet the specifications.”

Sen Mackenzie asked Mr King to confirm that he was suggesting that producers did not understand the grid pricing structure, and did not appreciate the complexity of the market in which they operated.

“We’ve heard from some incredibly articulate producers during this inquiry who very much understand the commercial realities they are operating in. What proportion of complaints about the system would you suggest are genuine and legitimate, and what proportion is through misunderstanding?” Sen Mackenzie asked.

“Up until 1998, we ran regular free AusMeat Feedback workshops across the country, with producers, and programs about assessing livestock. Some 5000 producers participated,” Mr King told her.

“Since 1998, when AusMeat was incorporated, after which producers had to pay for it, the program stopped within six months. I’m very conscious of that there is a lot of beef producers out there who are not aware of how grids really work. When we go through the process with them, they typically say, ‘Oh, I didn’t realise that’.”

“There is absolutely no doubt, as the inquiry has found, that there is a section of switched-on producers out there who know exactly what they are doing and have excellent knowledge in this area. But equally, I can honestly say that there are a lot of producers who do not have that understanding.”

Mr King said unfortunately, a lot of producers were relying very heavily on their agents, and therefore the ‘knowledge’ in this space resided with the agent, as opposed to the producer.

Complaints resolution

Asked to go through the complaints process, Mr King said producers with concerns about grading performance should initially go to the processor involved.

But if the producer did not get what they saw as a satisfactory result, AusMeat was also available for such complaints. Details are available via the website (www.ausmeat.com.au)

“All we need is the producers’ feedback sheet and some evidence that there is a situation, and we will follow it up,” he told the inquiry.

He stressed that AusMeat provided a service, that was independent, that was available both to producers and processors.

“We don’t have any affiliations with either group: we can’t afford to – we have to behave in a mutual way.”

“First and foremost, under such a claim, we ascertain whether the producer has understood the feedback sheet – because nine times out of ten under such circumstances, the complaint is based on misinterpretation of the feedback sheet,” he said.

“Do you collect stats on that?” Sen Mackenzie asked.

“I can definitely quantify it,” Mr King said.

Dispute settlement

Senator Mackenzie said processors had told the inquiry that they did not currently have any formal dispute settlement system in place to process such producer challenges on grading performance.

She asked Mr King whether Ausmeat had such systems in place, to which he answered in the affirmative.

“From both processors’ and producers’ points of view, there is no value in having disputes that cannot be effectively resolved,” he said. “We’ve certainly acted as an independent adjudicator in examples where they have come to us.”

Responding to a question about anonymity in such producer complaints, Mr King said if confidentiality was requested , it was given – but producers who had come forward with complaints in the past had typically been ‘quite willing’ for AusMeat to take the matter up with the processor involved on a joint basis. “It’s a learning process for both parties,” he said.

He confirmed that AusMeat had no role in the financial side in any dispute settlement between producer and processor. “We don’t have any jurisdiction over that. You want to give AusMeat more power, then do so, but currently the financial side of that dispute settlement is not our role.”

“I just want a process that works for both parties, in a fair way,” Sen Mackenzie said.

Audit process

Sen Mackenzie asked about the processor random audit process operating within AusMeat.

Mr King said since 1992, the process moved away from government to industry managed systems, based on quality management systems and procedures. It was very important that in that process, that independence be protected.

“First up, a meat processing company becoming AusMeat accredited gets a minimum of 12 audits a year – two of which are detailed audits, going through the entire language and measurement systems,” he said. The other ten were compliance or surveillance type audits.

Based on performance, the number of audits could then reduce to as low as four a year, based on quality management systems.

The remaining ten audits for new processors (figure not discussed for long standing Ausmeat processors), were random, meaning the inspector’s arrival was unannounced.

“There is no advance warning phone call, but the auditor simply arrives at the front gate. He has an audit plan in place before he even arrives, which the plant has no knowledge of,” Mr King said.

“Typically, the auditor may pick the slaughter floor, for example, as a key area of scrutiny, and may go through some of the quality traits and measurements process, including weighing, fat measurements or whatever else.”

Alternatively, the auditor might pick the boning room and go through the truth in labelling process or other attributes. The auditor also checked the specifications that the processor was working to, on that day.

“For example, if they are processing that day for the US market, we make sure that all the importing country requirements and labelling are being applied, as applicable to that market,” Mr King said.

Each individual audit was ‘customised’ on the day, depending on what that plant is producing.

Asked whether he could see any way that processors might manipulate grading results, to their advantage, Mr King said it “could not be manipulated for very long, without AusMeat picking it up.”

“Could AusMeat inspectors be pressured to give processors the grading results they wanted, in fear of being in some way disadvantaged?” senators asked Mr King.

“I don’t have any evidence of that occurring,” was his response.

Mr King said there was an average of six AusMeat audits each year across the 56 beef establishments accredited with AusMeat. Asked about the frequency of ‘failed audits’ he said it depended on what was classified as a ‘failure.’

“At each audit process, they are monitored against the standard, and given a numerical number. The average score for plans is 3.15, with a 4 considered not good enough, and a 3 above expectations, based on the A+ category.”

“But the range of results has come down significantly over the years,” Mr King said.

“In the early days, there was a lot of failures, but more recently, particularly with the big corporates getting involved, they run very sophisticated programs and the failure rate today is very, very low.”

“But on any one day, you could pick up a labelling issue or a fat measurement issue, or a chiller assessment issue. If there’s a level of subjectivity (as there is with many AusMeat assessments), the way it is controlled is through the computer-based correlation system developed by AusMeat, to try to get that desired uniformity.”

Mr King said when AusMeat auditors were on-plant, they were also Authorised Officers for the Federal Government, operating in an independent capacity.

When a senator asked about actions taken among audit failures, he expressed surprise to hear that in fact on two occasions, AusMeat processing licenses had been withdrawn.

Board structure

Inquiry questions also focussed on the makeup of the Ausmeat (and Language and Standards committee) boards – particularly over the apparent under-representation of the producer sector.

Mr King pointed out that the primary role of the AusMeat board itself, was the legal/fiscal responsibility for convening the committees that operated under the MOUs with government.

He said the Australian Meat Industry Language and Standards Committee which operated underneath it had not changed its composition in the past 23 years.

In fact in the 1998 industry restructure, it was reaffirmed by peak industry councils that the committee should remain is it was.

“Any process to change the structure of the committee would not be an AusMeat process, but would be something that the parties to the MOU – including government – would have to consider,” he said.

“Everybody across the industry sat around that representation process, and until the past 12 to 18 months, there has never been any challenge about the producer representation on the committee.”

“Why was there more processors than producers on the committee in the beginning? I can only answer that by saying that the original impact of Ausmeat (the authority for uniform specification) was mostly at the time within the processing sector, rather than the producing sector,” he said.

“The fact that the broader AusMeat activities now involve producers more, as we move into quality management systems on farm, has obviously raised some discontent, and potential for impact on standards. But in my 23 years, I can recall only one occasion when it was necessary to have a vote around the language and standards committee table.”

“At all other times, outcomes have been delivered by consensus among all stakeholders, and the result has always gone back to the peak industry councils before standards have been set and approved,” Mr King said.

I agree that there are some producers that don’t understand how to read grids, there are also a lot that have a very good understanding! They know that miss-split carcases can result in a heavy side falling out of the grid, they know that it only takes a slight push on a ruler to get the fat depth higher and therefore out of they grid and they know that if butt shapes are considered in a grid that this is purely subjective.

These producers understand that by the time they get their feedback and analyse it, if there are issues and a complaint is raised the product is often boned by this time and unable to be verified by the company or by AUS-MEAT. For this reason these producers know that it isn’t even worth raising the issue in the first place.

Good companies now take photos to prove teeth counts if they affect the price.

We use cameras to verify animal welfare, until purely objective systems are in place, why not have cameras in the grading stations (dentition, fat, weight, etc)?!? This system would protect everyone doing the right thing as no one should have anything to hide.

You (Australia) have the best grading/classification system in the world…………thus it is a pleasure to read about the minor problems with the system. Keep working on the details………to make the system even better.

During the Canberra session of this inquiry, AgForce representative Will Wilson tabled a paper that had the heading ‘Assessment Ausmeat Language’ some of the points mentioned were that the use of teeth does not describe Carcase Quality, as well as stating that it was well known that teeth are not an accurate measure of age. The use of accurate measurements must be used to gauge quality, the use of pH levels must be considered.

This paper was written by his father Rod more than 25 years ago, Rod Wilson was obviously a man before his time, we as an industry still have people of influence that maintain the use of things such as dentition and butt shape still have a place in a modern language that describes and determines the value of the product. I wonder if people such as Rod Wilson were in positions of influence all those years ago,whether we would be talking about an industry that had been driven by ‘commodity pricing’ for such a long time. Producers as Mr King explains may not fully understand processor grids, what they do understand is that in many cases they are supplying on a quality basis, yet being paid a commodity price.

As an old S&Stn agent 49 yrs since I commenced work I concur with Bob’s comments. I would like to see random audits done comparing what producers are paid by processors on their grids checking that the discounts given concur with the appropiate destination box from the abbatior

Taking in the above exchange, I tend to agree that lack of understanding of grid interpretation by some producers is a fairly common factor. Having sent many cattle over grids on behalf of producers for the past 30 odd years, I believe that the training of both producers (and agents) in converting live cattle into carcase specifications is still sadly lacking. Many producers are of the opinion that they can “cut corners” and save money by booking their livestock into a works themselves. These are often sent as a bulk lot to one works (often to save some freight) but in essence, a properly trained operator would split and either suggest holding the tail or, if the outside spec stock are passed the original grid parameters, send the tail to a different works, ensuring a decent price for the whole consignment. In a lot of cases the amount charged by a professionally trained operator to handle this on their behalf is more than paid for in the ensuing result. Producers will buck when their stock fall just outside a particular grid spec possibly by as little as 1 millimetre; but should realise that the grid target the processor is targeting, is actually well inside the outside parameters quoted. In the early days of sending grid cattle, some processors (in particular, smaller domestic works) made a habit of creating heavy discounting to suit their own advantage. In this day and age, with the competition for “over the hooks sales” – and the introduction of auditing, thankfully, this has been largely obliterated.