AS dams, creeks and rivers dry up across eastern Australia, the tightening grip of drought is again underscoring the critical value of groundwater to rural communities and agriculture.

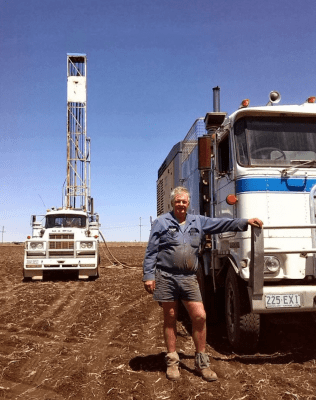

Bore drillers like Ian Hansen (left) at Dalby are receiving phone calls almost daily from livestock producers wanting new or replacement bores sunk as surface water runs out, while townships are also tapping further into groundwater to avoid running out of water.

Bore drillers like Ian Hansen (left) at Dalby are receiving phone calls almost daily from livestock producers wanting new or replacement bores sunk as surface water runs out, while townships are also tapping further into groundwater to avoid running out of water.

With precious and finite aquifers under considerable pressure, questions are again being asked about policies that grant short-term mining projects priority access to groundwater.

Evidence presented to a senate inquiry looking into ground water use last year showed the extractive gas industry in Queensland is permitted to take an unlimited amount of ‘associated water’ from coal seams in the course of regular operations. This water take occurs outside the State’s water licensing requirements as applied to other users.

In developing a new plan to oversee future water allocation from the Great Artesian Basin the State, the Queensland Government found that the impact of existing users, including the unlimited take by the extractive gas sector, had been underestimated.

The Queensland Government’s Great Artesian Basin and Other Regional Aquifers (GABORA) plan identified some 35,055 megalitres of currently unallocated water that can be allocated for future development in the basin.

However, the draft plan limits access to unallocated water for new agricultural developments, while encouraging the further roll out of the coal seam gas industry.

Of the 35,055ML available for future development in the GABORA Water Plan area, the plan reserves 28,610ML, or 80 percent, for major projects, mainly gas, mining and power stations.

5615ML, or 16 percent, is allocated as general reserve water for agriculture, and 830ML, or 4 percent, is Indigenous reserve for community projects.

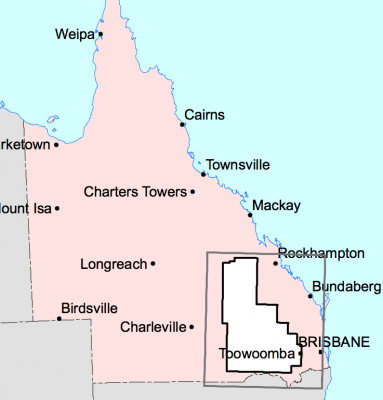

Specifically within the Surat Basin area (left), which a sub-basin of the Great Artesian Basin and home to half of Australia’s existing feedlot capacity, just 840ML of unallocated water has been made available for agriculture. This allocation is is also limited to deepest aquifer which is the most uneconomic to access.

The limitation all but prevents any chance of significant further expansion or future growth of the region’s large and economically important feedlot sector (click here to read earlier article).

The committee was told the CSG industry’s water take from the Surat Basin is 65,000 Megalitres per annum, in addition to the extraction of 52,000 megs per annum by all other users.

Across many regional, remote and arid areas of Australia, groundwater is the main or only source of water for human consumption, stock use and irrigation because of low or unreliable annual rainfall averages.

The committee of Senators conducting the inquiry concluded that while extractive projects provide economic benefits to certain sectors of the community, these benefits should not be prioritised at the long term expense of other industries or the environment.

“As the driest inhabited continent, and with climate change expected to affect future rainfall patterns, Australia needs access to underground water supplies more than ever, particularly because of the reliance of rural, regional and remote communities on these resources,” the committee wrote in its October 2018 report.

“As the driest inhabited continent, and with climate change expected to affect future rainfall patterns, Australia needs access to underground water supplies more than ever, particularly because of the reliance of rural, regional and remote communities on these resources,” the committee wrote in its October 2018 report.

In its comments to the inquiry the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association (APPEA) said oil and gas industry is a relatively small user of water extracted from the Great Artesian Basin compared with other industries.

APPEA’s Chief Executive Officer, Dr Malcolm Roberts, said agriculture ‘uses more water in Australia in a single day than the (oil and gas) industry uses in an entire year, and manufacturing used 22 times more water than the gas industry’.

APPEA says the gas industry’s water production rights are limited to what is necessary to produce natural gas, and this comes with responsibilities that don’t apply to other water users. It says the industry is required to monitor for water impact, fund reginal level modelling to forecase impacts, make good impacts on other water users, and beneficially re-use water where feasible. It says most of the water produced by the industry is used by local farmers, which is providing an importance source of water in drought.

The Minerals Council of Australia argued that the minerals industry often used water not suitable for other industrial purposes, including saline and hypersaline water’.

The International Association of Hydrogeologists also emphasised the mining industry’s relative value for money proportional to its total water use. This was echoed by APPEA, which contended that the oil and gas industry’s water consumption represented ‘exceptionally high economic value-add’ compared with other industries.

APPEA’s Dr Malcolm Roberts said groundwater use by the gas industry in Queensland was monitored and managed using a comprehensive network of monitoring bores to observe any impacts on water sources.

The Committee also heard from various submitters and witnesses who said figures comparing overall water use by different sectors did not equate to decreased impacts in comparison with other industries.

In the NSW Hunter region, for example, the committee was told the mining industry owned more than half of the high-security water licences in the regulated river and was a big groundwater user, particularly in the porous-rock aquifers.

Property Rights Australia Chair Joanne Rea told the inquiry that agricultural use of water in the Great Artesian Basin ‘is necessarily estimated, always overstated and has more to do with the capacity of bores than actual usage’. She contended that although agriculture may use a significant amount of water, its impacts are spread across ‘a wide area so that local impacts are minimal or manageable’.

Queensland and New South Wales are the only states in Australia where coal seam gas extraction is currently being undertaken, while other unconventional gas extraction involving fracking processes occurs in northeast South Australia.

Victoria, Tasmania and Western Australia have moratoriums in place on hydraulic fracturing activities, while the Northern Territory Government has recently announced a decision to lift a moratorium on fracking previously in place.

The South Australian Government has proposed a 10-year moratorium on fracking activities in the Limestone Coast area of the state’s southeast.

Some evidence also questioned the reliability of modelling used by extractive industries and governments.

Max Winders, a lot feeder and hydrologist in Southern Queensland, contended that detailed groundwater impact modelling that he commissioned his own environmental engineering company and a consultant to undertake on his property indicated ‘considerably more impairment’ to a local aquifer than did modelling provided by the Office of Groundwater Impact Assessment (OFIA).

The Queensland Government established the industry-funded OFIA to provide ‘evidence based independent scientific assessment of cumulative groundwater impacts from resource operations’.

A number of submitters drew the Committee’s attention to the lack of research surrounding impacts caused by water extraction and the interaction of different water resources more broadly.

Dr Lange Jorstad, the President of the Australian Chapter of the International Association of Hydrogeologists, said understanding of site-specific characteristics is often limited for large projects. Dr Jorstad described the information as ‘basically a set of pinholes in a very large mass of land. We make a lot of inferences about what is between those data points and how they interact with each other’.

The Law Council of Australia said knowledge of how underground water extraction impacts on surface water resources and dependant vegetation and ecosystems ‘remains patchy’ and contended more work needs to be done on developing scientific understanding of water resources.

“The lack of scientific knowledge around the interaction between surface and subsurface resources has infiltrated and is infiltrating the decision-making process, both at a regulator level and at a court level, and it is not satisfactory”.

Geoscience Australia argued that because groundwater impacts may take years or decades to become apparent, the regulatory system must ensure ongoing monitoring of water resources occurs.

The Basin Sustainability Alliance argued that water extraction by the coal seam gas industry in the Surat Basin had led to the depressurisation of two aquifers ‘to the extent that the agricultural sector is not permitted to construct any new bores into these two aquifers for intensive animal production or irrigation uses’.

Angus Emmott, a beef cattle producer from Queensland, was of the opinion that new coal and coal seam gas mines should not be approved where best science indicated a probability or even a high possibility of negative impacts.

He suggested that: “Feeding our people over the long term is a lot more important than digging a bit of coal to make some short-term money…I’m not against mining at all. As a society, we’re going to have to keep mining, but we have to use the best science and make sure we don’t destroy our food-producing system in doing it… If we damage the integrity of our groundwater systems and undermine the long-term sustainability of regional Australia and our water systems, then we really undermine the future of Australia. The idea of doing that for potentially short-lived economic gain that really doesn’t bring lasting benefits to the regions is deeply concerning.”

In submitting its final report the committee noted that Australia’s underground water systems are a precious and finite resource, and considerable room exists to improve Federal and State policy in terms of fair and equitable water allocation to ensure short-term economic gain does not outweigh the long-term water needs of agricultural users, rural, regional and remote communities and ecosystems.

To read the full senate inquiry report click here