The Australian Beef Sustainability Framework (ASBF) steering group says it strongly stands by the approach it uses to measure changes in tree cover in beef producing regions from year to year.

It follows calls by the World Wildlife Fund for a stronger reporting system for forest cover to be adopted nationally.

In a statement responding to the Australian Beef Sustainability Framework’s second annual report card released in June, the World Wildlife Fund said it applauded the leadership of the ASBF in committing to track the industry’s progress towards carbon neutrality by 2030.

However it also raised concerns about the framework’s reliance on the Federal Government’s National Carbon Accounting System (NCAS) to measure annual changes in forest cover and to claim net gains in woody vegetation over the past 30 years.

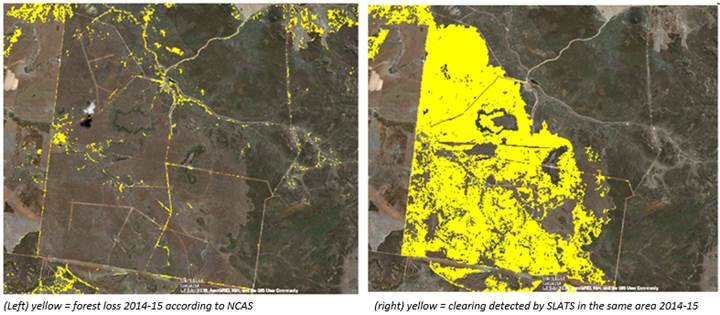

The WWF said the NCAS system that the Federal Government operates was not intended to track changes in tree cover and suggested it gives a misleading picture of actual forest cover, because it does not distinguish between spindly regrowth and 400 year old tall dense forests.

It wants the Federal Government to implement a system similar to the Queensland Government’s State Landcover and Trees Study, otherwise knowns as SLATS. (The Queensland Government’s own use of SLATS data to portray levels of tree clearing in the State has been heavily criticised by Queensland’s major farm representative group AgForce – more below).

In response to the WWF’s call the Australian Beef Sustainability Framework steering group says it takes the approach of using the best available data, and does not agree the information provides a misleading picture.

It points out it spent over a year working with an expert working group with expertise in ecology, beef production and remote sensing to develop evidence-based and practical measures to add certainty and credibility to what has long been a contentious topic.

It says the only available national data set for changes in forest is the National Carbon Accounting System.

While not perfect, all stakeholders engaged in the refinement of indicators used – including WWF and other environmental groups – agreed that it was the best possible dataset available, the ABSF steeting group said.

WWF position

In its response to the ASBF update in June, the WWF said it applauded the Australian beef industry for taking a leadership position to reduce its environmental impact.

The cattle industry was threatened “more than most” by climate change, and its commitment to transparency and to record progress towards the target of carbon neutrality by 2030 sent “a powerful, positive message”.

However, the WWF singled out for criticism the industry’s use of the Federal Government’s National Carbon Accounting System to claim a net gain in the total area of woody vegetation across beef-producing regions.

The WWF’s position is the NCAS does not provide an accurate picture of changes in forest cover. Instead it says a system like the Queensland government’s State Landcover and Trees Study (SLATS) should be used, which it says represents ‘global best practice’ in annual accounting of tree cover.

The NCAS uses satellite images to model annual changes in forest and woodland cover and is the only system that provides nationwide measurements.

The WWF’s Ian McConnel addressing the 2019 Northern Territory Cattlemens’ Association conference in Darwin earlier in March.

Ian McConnel, WWF Global Commodity Leader – Beef said the WWF’s concern is that the NCAS does not distinguish between “spindly regrowth” and “400 year old tall dense forests”.

Once regrowth foliage covered 20 percent of an area, it “was counted the same way”, he said.

That could happen as quickly as a single year with regrowth that was only waist high.

“For example, if 100 hectares of 400 year old forest are bulldozed but elsewhere 110 hectares of regrowth reaches the 20 percent threshold, then that is counted as a net gain in woody vegetation” Mr McConnel said.

“No-one could possibly argue that represents a net gain in forest.”

Mr McConnel said a crucial requirement for any credible sustainability report was conserving wildlife. Studies suggested the smallest tree-dwelling marsupials and hollow-dependent birds could begin to recolonise regrown trees after about 165 years, but hollows suitable for larger animals would not be available until over 200 years.

The WWF wants the Queensland government’s SLATS system to be expanded nationally, which would remove the need to use the NCAS data that was established for carbon accounting, not measuring changes in trees.

“Under NCAS forests can be thinned from 100 percent canopy cover down to 20 percent and still be called forest.

“This inevitably misses out on large areas of tree clearing, and because ABSF relies on NCAS, these areas are missing from their forest change statistics,” Mr McConnel said.

“We need a single point of truth on deforestation and carbon in Australia. You can’t sustainably manage what you can’t accurately measure.”

Mr McConnel noted that the ABSF update reported a 3.5 percent reduction in primary forest over the last five years, which included “an alarming 8 percent reduction in Reef catchments”.

“This loss of biodiverse primary forest cannot be offset by new, younger forests. The beef industry needs to commit to ending deforestation of all primary forests and high conservation value regrowth,” Mr McConnel said.

He said global market demand was pushing for deforestation-free commitments to be delivered by 2020, as evidenced by the various signatories to the New York Declaration on Forests, the Consumer Goods Forum and the Sustainable Development Goals.

At the same time reforestation and land rehabilitation presented an emerging and growing income stream for producers, based on carbon and other environmental credits.

“That means vegetation management to conserve biodiversity and increase carbon storage should be factored into future industry plans,” he said.

ASBF: Data looks at both increases and decreases

In response to the WWF’s concerns the Australian Beef Sustainability Framework said it has enabled reporting in changes in the balance of tree and grass cover across beef properties for the first time in this year’s report.

The data in the report looked at both increases and decreases in trees and pastures for the past 30 years across 56 regions.

This addressed a key criticism that the industry has about the SLATS reporting system in Queensland and enables a more holistic picture of changes over time.

In order to develop the world-first dataset, the framework spent a year focusing on developing evidence-based and practical measures to add certainty and credibility to a contentious topic.

In developing the new indicators the Sustainability Steering Group sought advice from an Expert Working Group with expertise in ecology, beef production and remote sensing to identify the best indicators and the most appropriate way to measure changes in trees and pastures.

“The framework is about leveraging existing data sets to report on what our stakeholders, including customers, investors and the community tell us they are interested in,” an ASBF statement provided to Beef Central said.

Currently the only available national data set for changes in forest was the National Carbon Accounting System and this was used as the basis for the remote sensing work undertaken.

While this data set is not perfect, all stakeholders that were engaged in the refinement of these indicators, including WWF and other environmental groups agreed it was the best possible dataset available, the ASBF statement said.

“The framework agrees that a strengthened national monitoring service that distinguishes between different classes of vegetation is required.

“This is a clear area of interest from our major customers and we need, as an industry, to work with government on how we can access data to demonstrate our performance in order to maintain our world class reputation.”

Selective SLATS science

Queensland rural lobby group AgForce has been highly critical of the Queensland Government’s use of information generated by the SLATS system to justify its claims that its Vegetation Management Act (VMA) was required to prevent land clearing for agriculture in the State.

AgForce has said the Queensland Government has selectively and creatively used ‘cherry-picked’ SLATS data to only tell half the story, while not releasing the full reports to the public.

“The Government’s heavily edited version of the SLATS report doesn’t mention that most clearing is done to provide feed to prevent livestock from starving during drought and to maintain land, including controlling weeds and invasive species that compete with native vegetation,” AgForce president Georgie Somerset said in response to the Qld Government’s December 2018 release of SLATS data.

“The Government’s heavily edited version of the SLATS report doesn’t mention that most clearing is done to provide feed to prevent livestock from starving during drought and to maintain land, including controlling weeds and invasive species that compete with native vegetation,” AgForce president Georgie Somerset said in response to the Qld Government’s December 2018 release of SLATS data.

“The ‘football fields’ of cleared land quoted in their media release represents just 0.2 percent of total Queensland land area.

“It also doesn’t mention that around 40 percent of this area has already been cleared and is simply being maintained.

“And it only measures how much land has been cleared, not how much vegetation has grown over the same period.”

She said AgForce had argued for years that Government scientists should have the resources they need to examine how much vegetation was growing, not just how much was being cleared.