THE rapid uptake of genotyping as described in last week’s genetics review raises new opportunities for breeders to determine the potential of their entire herd.

Traditionally, performance recording has focused largely on male progeny. This trend has continued with the introduction of genomic testing, with most records collected from effectively only half of the progeny born in a program.

With the increased uptake of genomic testing in Australian herds, there is an accompanying uptake of breeders testing both bull and heifer calves, and developing a much more comprehensive profile of the genetic potential within their herd.

Some breeds such as Angus already have a fairly equal proportion of male and female calves tested annually. Angus Australia’s Andrew Byrne suggested that the collection of data at calving using Tissue Sample Collection has significantly helped ensure profiling occurs across an entire calf drop.

However in other breeds, the decision to test females as well as males has been slower.

One of the impediments has been the cost associated with testing. While many some societies offer testing packages to include tests on genetic conditions or parentage verification, at around $60 for a 50k panel test, seedstock breeders are closely considering what the returns are on this investment.

The decision to test an entire herd probably should be taken in the context of what will that information mean to a program’s overall objectives.

Genomic testing offers breeders information that can be useful in three key areas:

- Parentage verification

- Management of genetic conditions, and

- To contribute to breed information in Breedplan analysis.

These three areas are key considerations for many seedstock breeders. Parentage verification is perhaps one of the most important issues, particularly when it comes to listing and offering sires for sale. While breeders attempt to be vigilant in their recording of matings, errors can and do occur.

There are numerous ways in which errors can happen when recording parentage. Herds that use multi-sire matings and uncertainty between AI and back-up bulls are two of the more common reasons for errors. However other incidents that can range from a visiting bull through to mis-mothering calves or just straight out human error.

Minimising the risk of incorrectly describing a bull’s pedigree at sale is a significant driver behind many breeders’ decisions to undertake sire verification.

Angus Australia recommends all sale animals be DNA sire-verified as a minimum standard. The society has gone further within its regulations, requiring the display of parentage verification status of sale lots using the following suffix to an animal’s name:

- PV – both the animal’s parents have been verified by DNA

- SV – the animal’s sire has been verified by DNA

- DV – the animal’s dam has been verified by DNA

- # – DNA verification has not been conducted

- E – DNA verification has identified that the animal’s sire and/or dam may possibly be incorrect, but this cannot be confirmed conclusively

Outside of the Angus breed, sire identification remains one of the primary drivers for seedstock breeders’ genotyping decisions. However in several breeds the management and early identification of genetic conditions is also a high priority.

Genetic conditions can be prevalent in some herds and may not be recognised until significant production losses occur. Genetic conditions can impact a range of production areas, from growth and fertility and structural soundness. Other issues may result in early mortality of calves.

Often, and in extensively-managed herds, the symptoms of genetic conditions can be non-specific and difficult to recognise. Often calf losses are attributed to other factors such as environmental impacts or predation. However, when these issues continue over several seasons, breeders have started to look more closely at their herds, to see if genetics is playing a role in these losses.

While many purchased sires have information regarding their genetic status, the cow herd remains the unknown. It’s in these situations that genetic testing is required to manage and reduce on-going losses. At a practical level, the information provided from genetic testing allows breeders to avoid joining carrier dams to a carrier sire.

Without knowing the status of cows, the options for breeders are restricted to using only those sires which are tested free of the conditions that are of concern. Potentially this reduces the choice some breeders have for sires. The additional benefit in testing females allows breeders more flexibility in managing their herd to eradicate that trait within the herd.

The additional benefit of genetic testing, particularly within the breeds undertaking Single Step Breedplan (so far, Angus, Hereford, Brahman and Wagyu) is the improvements in data and accuracy of the EBVs offered by each breed.

From a practical perspective, commencing herd testing can be done in several ways depending on each breeder’s overall breeding objectives.

Catriona Millen of SBTS describes the approach as one which should line up against those objectives. She said “If it’s full parentage verification a producers wants, all dams of the calves they wish to do parent verification on will need to be genotyped. This could be for all calves in a calving year, or a select subset (e.g. full parent verification on sale bulls only).”

For producers who are managing genetic conditions, she said it may be that they only genotype cows from certain lines that contain known carriers.

One option to genotype a herd can be to commence testing with yearling heifers prior to selection. This information can aid in both identifying carriers of any genetic conditions as well as using it for sire ID purposes or to group into lines based on other production traits. This approach allows a decision to be made about animals that are genetically unsuitable prior to joining.

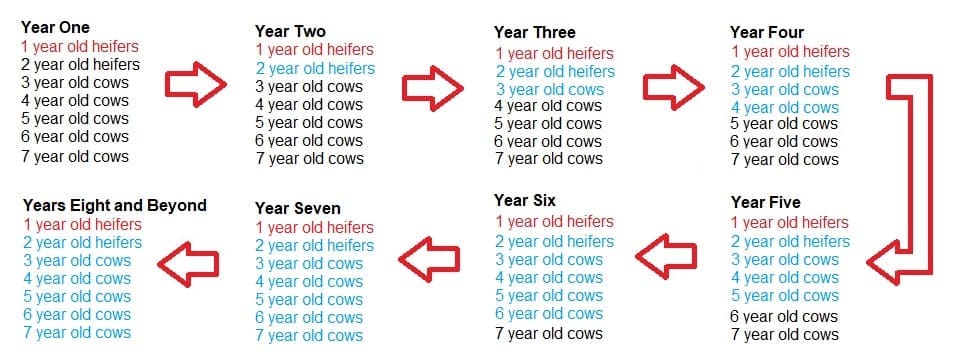

While this process does take longer than testing an entire herd in one year, it is a more practical approach and allows producers the opportunity to make more balanced selection decisions based on the best information for the entire herd.

Alastair Rayner

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. He regularly attends bull sales to support client purchases and undertakes pre-sale selections and classifications. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Sometimes your headline questions are way too easy to answer…………

NO