IN breeding cattle, joining is a make-or-break period, in more ways than one.

In areas where controlled matings are used, production levels for the following season are determined by events that occur during a 6-12 week window.

While much attention is placed on the numbers achieved in that first year, a poor joining event can have long-lasting impacts on herds reliant on selecting replacement heifers from each year’s group of calves. A poor outcome at joining can delay or set back programs for two or three years.

While much attention is placed on the numbers achieved in that first year, a poor joining event can have long-lasting impacts on herds reliant on selecting replacement heifers from each year’s group of calves. A poor outcome at joining can delay or set back programs for two or three years.

Joining preparation focuses on strategies designed to achieve the best outcomes. Much of these preparations address critical areas such as body weight and condition.

Additional strategies such as Bull Breeding Soundness Examinations – or at the very least bull inspections assessing any structural issues, as well as inspecting the testicles and sheath – should be part of routine preparations.

While these preparation strategies are essential, joining is a physical activity, and despite all preparations, accidents do happen. When they do, the result of the accident can range from a spread-out calving next season, through to a significant drop-in pregnancy rate, and may also include the financial loss of a bull through permanent damage.

As accidents can’t always be prevented, joining is a time of risk. However, as with the lead up and preparation for joining, there are some strategies that producers can undertake to reduce the risk of accidents occurring.

One of the greatest causes of accidents comes through fighting among bulls. Fighting is the result of bulls seeking to establish a hierarchy or as some call it a “pecking order”.

The establishment of social hierarchy can occur reasonably quickly – within a few hours, or it can take several days. In most cases dominance is determined by age. However, weight and size are also significant contributors to a bull’s position within the group.

For this reason, producers should consider bringing their joining groups together well before joining commences.

It isn’t possible to prevent fighting. Instead, the risk should be minimised by grouping bulls together by age and weight.

Groups should be put into paddocks where there is sufficient space for bulls to not only establish their position, but to allow the bulls room to move and avoid ongoing conflict. Allowing bulls some space often reduces stress and tension in the group, which can help reduce the intensity of the social structuring process.

In doing this, it’s likely there will be less risk of injury or damage to infrastructure which can occur when bulls are kept too close together.

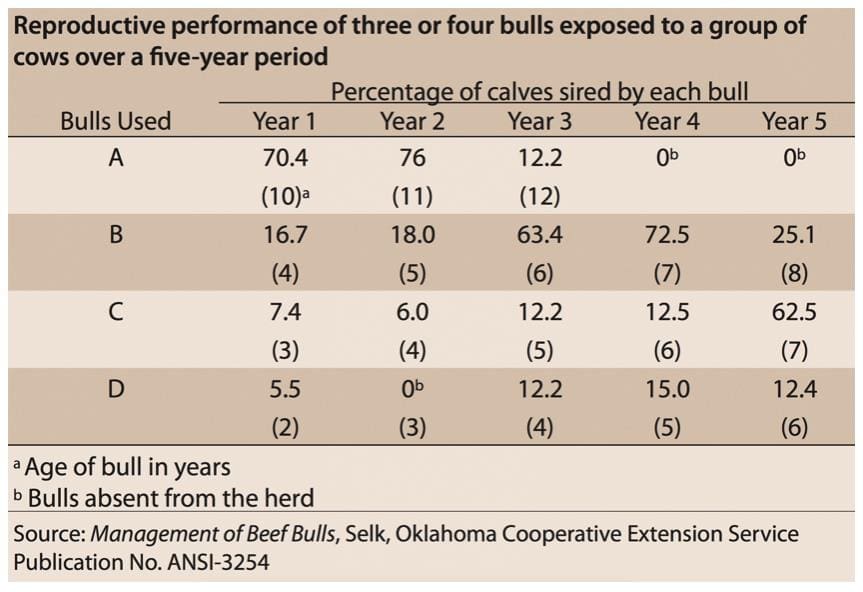

While fighting is the most obvious issue for many producers, the influence a dominant bull can have is reflected in the number of conceptions achieved. Some interesting research from the Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service demonstrated the influence age has on conception rates in beef herds over a number of years.

Source: Management of Beef Bulls, Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service

There are two basic results to consider from this data. The first is the dominant bull sires the greatest percentage of calves. The second is that up to a certain point, age is the primary driver of dominance in the group.

One of the greatest risks with multiple-sire joining, particularly with groups of bulls that have age differences, is the risk the older dominant bull may be sub-fertile or even infertile.

As a dominate bull he will prevent other bulls from mating, and as a result those cows in oestrus will not be joined at all. The work of Mike Blockey in the late 1970’s demonstrated that mixed age bull groups achieved lower pregnancy rates when compared to groups joined to bulls of the same age.

Ensuring the ratio of bulls to cows is correct should be a factor included in preparations to reduce joining accidents. Higher ratios (as identified in an earlier Beef Central article) does not translate to higher conceptions.

One issue with higher ratios was identified by Mike Blockey. Social interaction among bulls – sorting dominance, has a higher influence on herd reproduction when there are less cows per bull.

There is strong evidence from a number of studies that towards the end of joining periods, unmated cows are often a result of bulls that have become less efficient either from over-work or for their involvement in physical activities to maintain their social dominance order.

Regular checking

Regular checking of mating groups should be an essential part of the joining process, particularly in the first month of the program. During this time, bulls should be working the hardest. In a typical herd, at the start of joining around 5pc of cows within the group will be in heat daily.

To achieve a target of 65pc of calves born in the first 21 days of the calving season, in a group of 100 cows, a bull should be serving between three and five cows each day. While this number does not seem to be overly large, bulls still have to find these cows and serve them successfully. In fact, the actual number of matings may be higher, as not every mating results in a conception.

This period sees the most physical pressure on bulls and increases the risk of injury – particularly to a bull’s penis. A broken or injured penis can be identified by sight of the injury or through observing swelling on the underline through to the scrotum.

Other injuries such as lameness of stiffness are also common. Lameness is often best observed when the bull first gets up and begins moving around.

Regular checking, particularly in the first cycle, is essential to identify any issues and to take a bull out of the group if he appears unable to serve cows successfully.

It is important to recognise that while a bull may be unwilling to serve cows due to injury, he may still continue to exert his dominance over the other bulls and prevent them from serving cows as they come on heat. This intimidation can result in later conceptions or a significant drop-in overall conception rate.

If problems are identified its best to act early and remove the bull in order to salvage the rest of the breeding season. In the context of next year’s calving, it is better to have a group of late calves than no calves at all.

Once joining is over, bulls should be returned to larger paddocks and given a chance to regain condition or recovery from any injuries if they were removed earlier in the period. Again, having a larger paddock is a good idea to let bulls sort their order out and settle down as a group without too many issues.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au