SELECTION decisions underpin the long-term viability of any beef enterprise. These decisions include those made on phenotype as well as on genetic potential of new sires to make changes across a herd.

Genetic improvement is a long-term process that offers cumulative improvements.

The results of genetic selection can be seen in the first generation of animals. However, it is also important to be realistic when considering the scale of these changes, especially across a large herd.

Many producers have great expectations about the degree of change they can expect from the introduction of a new sire into a program. Unfortunately, single sires can only contribute so much to a herd. Using a number of new sires may actually see some measurable changes, and over several years these changes may become more pronounced.

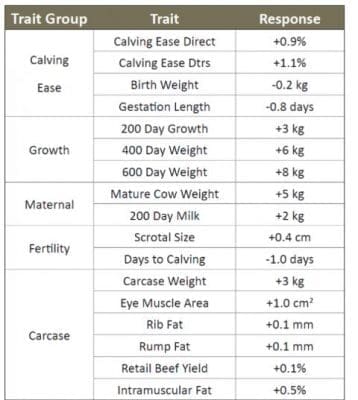

Source: Angus Australia – Indicative response to Selection (Angus Breeding Index)

The degree of change is dependent on the choice of sires. Sires selected that are above breed average will create measurable change.

As an example, Angus Australia identifies the level of change producers could expect within one generation when using bulls selected for their breed index values.

In the example at left, producers could expect a degree of change to major production traits in the calves sired by a bull selected using the Angus Breeding Index.

The practical outcomes are slight increases in growth and carcase traits in the first generation. This impact will be felt as more animals are joined to superior sires.

The rate of improvement across a herd is a result of the selection intensity applied to the breeding herd as well as that used to select new sires.

This intensity will directly impact on the time period that will pass before producers can start to record significant production change across their broader herd.

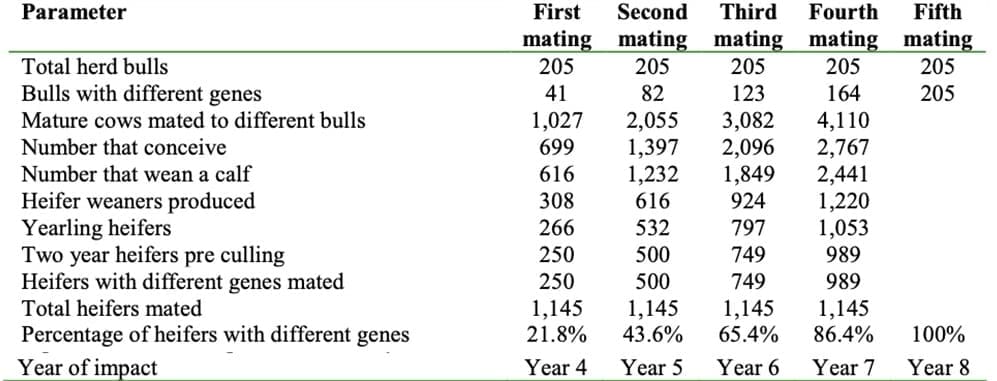

Source: Improving the performance of beef production systems in northern Australia (2019)

Impact from introduction of new sires

Previous Beef Genetics columns addressed the time-frame producers should allow for the introduction and expression of new genetics within a herd. In herds where new bulls are introduced annually, the impact on a breeding herd is generally no less than three years and is often closer to four years as those heifers enter the breeding herd.

The timeframe of introducing new sires to a breeding herd has been explored in the 2019 report “Improving the performance of beef production systems in northern Australia” prepared by the Queensland and Northern Territory Governments.

The analysis focused on the costs associated with replacing bulls over time with superior genetics.

As the table demonstrates, the time-frame for the new genetics to move through the herd is significant. It takes eight years for all the heifers in a herd to have their share of the new genetics a producer has selected for, and it isn’t until the thirteenth year after the decision to change has occurred that the whole herd has the new genetics.

This doesn’t suggest that making genetic change is not an option for producers. Genetics offer long-term and cumulative changes, which implies herds will benefit each year as the genetics diffuse through the population, allowing greater capacity to measure and record performance improvements.

However, it’s important that in recognising the length of time genetic change takes, producers don’t lose focus on the opportunities to address short-term strategic changes. Making time to reflect on current herd performance is essential.

While there may be long-term goals that genetics will help a herd achieve, it is just as likely there are management strategies which could be undertaken in the short-term to achieve a similar response.

Production traits such as growth or fatness, can equally be achieved through changes in strategic management. As a practical approach to improvement, producers should consider the areas they can influence and the traits that matter to their market targets.

Often this reflection allows producers a chance to firstly redirect their focus on some “easy wins.” Management decisions such as joining length, stocking rates, or weaning times will all have direct impact on cow herds and the expression of genetics within the herd.

From a practical perspective, producers should temper their expectations for the degree of change they expect to observe as a result of using their new sires.

While change is occurring, the results will take several years to be fully realised. In the meantime, it’s essential not to overlook or underestimate the importance of strategic management on the expression of the genetics already within the breeding herd.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au