Limousin cattle have made big inroads into temperament, since EBVs for docility were introduced in 2000, Breedplan data suggests. The average docility EBVs in the breed today would have been equal to the top 5-10pc of the breed 15-20 years ago, a prominent Limousin breeder suggests in this contributed article….

REGARDLESS of which breed they use, when asked what the most important factor is in bull selection, Australian cattle producers consistently rank temperament as number one, an Angus Australia survey conducted last year shows.

Temperament (or docility) is the way an animal reacts to an unfamiliar or challenging situation, and is the result of both genetics and environmental effects.

The trait affects profitability, through impacting production costs, meat quality, reproduction and maternal behaviour, animal welfare and handler safety.

Docility is one of the most heritable traits currently being recorded, and genetic selection has played a key role in improvements in docility scoring over the past two decades.

Docility scoring is a subjective measure of an animal’s response to being restrained and isolated. Calves are scored at weaning or shortly after, when all calves have had similar handling, reducing the variation in handling prior to scoring, and allowing the variation in temperament to be expressed.

Calves are scored using the crush or yard test, on a scale of 1 (docile) to 5 (aggressive), with EBVs calculated using the docility scores from seedstock animals.

Limousin breeders began scoring docility in calves in 1995. The strong genetic improvement in docility in Limousin cattle is the result of selection pressure placed on docility by the breeders and the Australian Limousin Breeders Society.

Once EBVs for docility of sires became available in 2000, the breed started to make significant genetic progress and has continued this progress steadily since then.

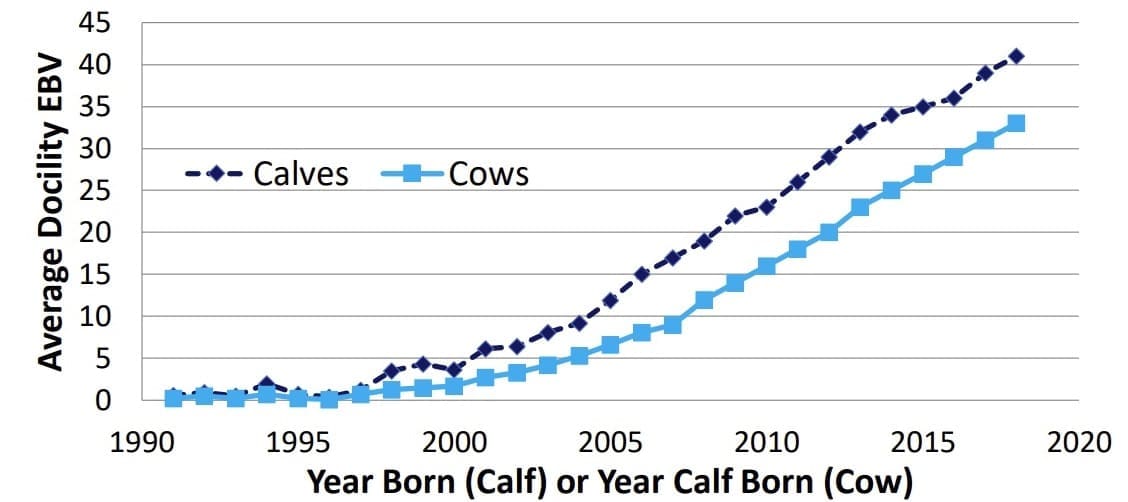

The average docility EBV for 2018-born calves was +41 compared to an average of +3.5 for calves born in 2000. The average docility EBV for dams has also increased steadily from +1.5 in 2000 to +33 in 2018, due to culling of cows with poor docility EBVs and having replacement heifers with good docility EBVs to select from (see Figure 1).

Average Docility EBVs for Limousin calves born (1991-2018) and their dams.

Source: Australian Limousin Breeders Society (2019)

The average docility EBV of the 20 most widely used Limousin AI sires has also increased from +0.5 in 1998 to +48.7 in 2018.

Holbrook, New South Wales Limousin breeder Rick Tindal was instrumental in the push to measure docility and the development of docility EBVs in Australia. After returning from the United States in the late 1980s, he started the docility conversation with the ALBS board.

“Some members were antagonistic when we first started talking about docility,” Mr Tindall recalls.

“But as breeders started to embrace the idea and see real differences through the selection of bulls with high docility EBVs, the genetic gains were exceptional. It’s the best thing the Australian Limousin Breeders Society has done,” he said.

Limousin breeder and board member Michael O’Sullivan agrees. “Objective measurements have allowed significant genetic improvements in the breed. Until you starting measuring traits, you are really only making a best guess,” he said.

“When you have a number against a trait, people start to look more at their cattle and make better management and breeding decisions, which ultimately leads to big gains within their herd and across the breed.”

“The average docility EBVs in the Limousin breed today would have been equal to the top 5-10 percent of the breed 15-20 years ago, showing how far we have come,” Mr O’Sullivan said.

Selecting sires with higher docility EBVs than those used in previous joinings results in long-term genetic improvement in temperament, which impacts significantly on herd productivity and profitability.

What does this mean for the commercial producer?

Temperament strongly impacts carcase quality, increasing the number of dark-cutters, reducing meat tenderness and increasing the percentage of bruised carcases. In a 2014 report, Meat & Livestock Australia estimated 10pc of beef carcases were categorised as dark-cutters, resulting in a discount of up to 45c/kg hot carcase weight. This equates to a loss of about $36 million annually to the Australian cattle industry.

Lyndhurst, NSW commercial cattle breeder Ashley Clarke says temperament should be a key attribute in any breeding program.

Prior to the recent drought, he joined 700-800 British and Euro breed cows (50pc Limousin genetics) to Limousin bulls, turning off calves at around 420-500kg predominately into the domestic market for Coles supermarkets.

“Temperament, maternal attributes and ‘softness’ are the key things we looked for when selecting bulls for use in our herd,” Ash said. “While calves were quiet when younger, continued handling as they grew out, saw them quieten even further. This calmer temperament has resulted in very few being categorised as dark-cutters over the years,” he said.

Temperament also affects reproduction, animal health and liveweight gains. Research undertaken at Oregon State University by Professor Reinaldo Cooke, found that cattle with docility scores of 1-3 generally had higher conception rates, calving rates and weaning weights.

He also reported that heifers with calm temperaments reached puberty earlier than their more temperamental cohorts. Temperament can also affect immune responses in cattle. As cattle become more excitable, cortisol concentrations in the blood increase, resulting in immuno-suppression, meaning cattle are more susceptible to disease.

The research also showed that as cattle become more excitable, their average daily gain decreased. Professor Cooke explains that this can be attributed to cattle watching and reacting to potential threats rather than grazing; dietary nutrients that would normally be used for weight gain being reallocated to respond to the changed behaviour (potential threat); and the altered body physiology directly impairing liveweight gain (e.g. muscle and fat deposits are broken down, releasing energy and protein to support the response to the potential threat).

Warren Barnett

Mathoura, NSW lotfeeder Warren Barnett, from Associated Feedlots, says temperament is a product of handling and livestock management.

“We turn off 18,000 to 20,000 head annually, with a number of Limousin cross cattle going through our feedlots. We have implemented a program of acclimation and exercise into our feedlots, creating a sense of trust between the cattle and those who handle them,” he said.

“This ensures cattle are calmer and handler safety is also improved. Our stockmen ride horses, reducing the predatory threat seen by the cattle and we have also redesigned our stockyards to ensure better footing and good vision.”

A flatter print on the concrete flooring ensures cattle do not slip as easily, and running four rails (26 cm apart) rather than six allows cattle to see out and see what’s coming towards them.”

The calmer temperament also helped with handling sick animals in the feedlot.

“The cattle are not as aggressive and our stockmen can move them more easily, and recovery is quicker,” Mr Barnett said.

A chance conversation with a neighbour in 1992 saw the Heffer family from Tarcutta, NSW introduce Limousin genetics into their crossbreeding operation. The Heffers sell predominately into the vealer market, turning off calves at 9-10 months weighing 350-360kg (steers) and 330-350kg (heifers).

“Temperament is critically important and is a key selection criterion when we purchase bulls,” Helen Heffer said.

“People often use to say to us that Limousin’s were mad, but we haven’t experienced this. Selection of bulls with high EBVs for docility, coupled with handling cattle from a young age means we have next to no issues with temperament in our herd,” she said.

“We cull heavily on temperament with any stirry animals run straight onto the truck. There is no place for them in our herd,” she said.

Source: Toni Nugent, ALBS

We have had limo s for about30+ years n temprament has greatly improved as well as type

A different breed to the ferals of twenty years ago thanks to Alex McDonald.

Well done to Rick and the other stewards of the breed for having the courage to admit that our breed had a problem and realising that this admission was the first step to fixing it. I recall in the early 90’s, one of the Limousin bulls we were using was quiet himself being an ex show (led) bull. However his calves weren’t – if they weren’t trying to eat you in the yards they were clearing the top rail of them like gazelles. Later, when breedplan EBV’s for docility were first released we could trace the problem to the bull’s sire who was in the worst 10-20% of the breed for docility. Since that time we started buying bulls and breeding bulls at the other end of the EBV spectrum for docility and the problem disappeared. It showed me how using objective data to measure and improve cattle traits could turn a weakness of the breed into a strength.

Thanks for your comment, Mark. So often the case that it is more important to trim the outliers at the bottom (left hand side) of the bell curve for any trait, rather than try to lift the performance at the right hand side. The average automatically shifts to the right. Editor