AT first glance they could be mistaken for the world’s loneliest mobile phone towers.

But rather than helping people to phone a friend, the steel masts and high-tech sensors now appearing across a network of grazing properties are being used to communicate the story of how carbon is being captured in Australian cattle paddocks.

Covering areas of 10 to 50 hectares, the “flux towers” as they are called measure wind speed, along with changes or ‘fluxes’ in gas concentrations in the air, 20 times per second.

The data is then applied using a method called ‘eddy covariance’ to delineate the movement of carbon between the air and the ground in real time.

Changes in paddock conditions – such as preparing ground for planting, phases of pasture growth, wet conditions, dry conditions, and burning events – cause carbon to be either drawn down from the atmosphere into the soil, or lost from the soil into the atmosphere.

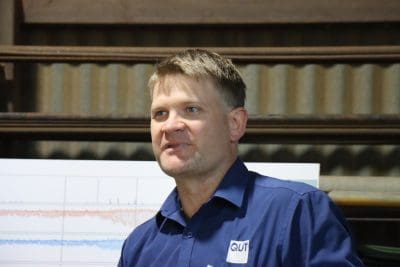

The key processes at play are photosynthesis and respiration, QUT soil scientist Professor Dave Rowlings explained at a recent field day at the Quinn family’s property Essex at Middlemount.

The key processes at play are photosynthesis and respiration, QUT soil scientist Professor Dave Rowlings explained at a recent field day at the Quinn family’s property Essex at Middlemount.

“Photosynthesis is what drives carbon going into the soil through the plants, and with respiration, just like humans, microbes break down that carbon in the plants and they breathe out CO2.

“With the flux towers we measure the total amount of photosynthesis and the total amount of respiration.

“So we look at that balance between carbon going in through photosynthesis and carbon coming back out through respiration, and depending on that balance, if we have a positive or a negative, tells us if we’re a sink or a source.”

The output he says is “really, really high resolution data”.

“The crux of it is we’ve got a laser that’s measuring CO2 and water vapour 20 times a second, and we pair that with a three-dimensional wind speed monitor, also at 20 times a second.

“The crux of it is we’ve got a laser that’s measuring CO2 and water vapour 20 times a second, and we pair that with a three-dimensional wind speed monitor, also at 20 times a second.

“So it tells us if the carbon that’s traveling across your landscape is enriched in CO2 – so you’ve got a loss – or it’s or it’s depleted in CO2 – so it’s been drawn down.

“And we do this 20 times a second, 24 hours day, 365 days a year.”

Decades old technology now helping to tell the cattle/carbon story

Eddy covariance flux towers are not new, having been used since 1951 to measure how ecosystems interact with the atmosphere. There are many in use, with the FLUXNET global research network incorporating more than 1000 flux towers worldwide.

But the idea of using flux towers for the purpose of measuring carbon flows on cattle properties is far more recent. (See more stories below about how the technology is being used in the US).

The concept was first applied in Australia by family-owned agricultural technology business and pasture legume supplier Agrimix in 2021, when it commissioned a large-scale research project with flux towers across a network of Queensland cattle properties in partnership with the Queensland University of Technology (QUT).

Flux towers do not come cheap, with each unit costing about $150,000 to establish. $11 million has been committed to the flux tower project to date, shared by Agrimix itself, private cattle businesses involved in the research and Meat & Livestock Australia.

Reducing the cost of on-farm carbon measurement

Proponents believe flux towers can dramatically lower the cost of on-farm carbon measurement for farmers, including those looking to participate in carbon credit offset schemes by adding carbon to the soil through changed management practices, such as introducing deep-rooted legumes to existing pasture mixes.

The field day at Essex was told that carbon is very hard to measure accurately because of the spatial variability of soil carbon that occurs across a given area of land.

Large numbers of soil core samples are needed to adequately capture the spatial variability Professor Rowlings said, which is a labour-intensive and costly process.

The flux tower technology, and the data it is collecting to underpin future modelling, has the potential to make that cost much more affordable for producers, the field day was told.

In terms of the accuracy of the technology, the research had shown “very, very good correlations” between what flux towers are measuring and what intensive soil sampling is also showing from the same area of land.

What are flux towers on cattle properties showing so far?

One question Professor Rowlings said he is often asked is “can you actually sequester carbon?”

The research in Central Queensland was showing that deep rooted legumes can put “a lot of carbon down into soil”, he said, and was demonstrating that carbon can be sequestered and at rates where “carbon neutral beef is a real thing”.

“The potential is there,” he said.

“Unfortunately you’re not going to get Desmanthus (a deep tap-rooted legume) across all your properties, but at least on those areas, the potential is there.”

The technology is helping producers to understand where soil carbon losses can come from, and because it is being provided in near real time, to understand what they might be able to do to mitigate those losses, Agrimix agronomist Zac Geldoff said.

Not every property will require a flux tower in future, the field day was told.

Modelling from the data being collected enables the creation of “digital twins” of any property, allowing different management systems or climate variations to be simulated to determine how those changes would affect future soil carbon stocks on that property.

One property involved in the trial increased soil carbon from 33.6 tonnes per hectare to 34.4 tonnes per hectare over an 18 month period following blade ploughing and then adding deep-rooted legumes to the existing buffel pasture. More details on the results to date will be reported when they become available.

QUT now oversees a growing network of flux towers as part of the Australian Long-Term Agricultural Research (ALTAR) initiative. The agricultural network complements the existing Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (TERN), which primarily monitors natural systems. By embedding flux towers across diverse production landscapes, the ALTAR network generates long-term, high-resolution data that is critical not only for advancing scientific understanding but also for supporting the Australian beef industry’s sustainability narrative with robust, empirical evidence, the QUT team explained.

One (1) property ( were there others ? what happened ? )involved in the WTF Flux Tower trial increased soil carbon from 33.6 tonnes per hectare to just 34.4 tonnes per hectare (+ 0.8 tonne ) over an 18 month period following blade ploughing and then adding deep-rooted legumes to the existing buffel pasture.

Minus the carbon used in spraying ploughing seeding etc = zero or negative carbon… a real trial doing nothing but grazing cattle (turning grass into soil compost) would prove less costly and deliver similar results..

Cattle grazing isnt any issue unless in drought or overgrazing which leads to the question… is ANY grazing or farming possible in semi arid drought prone SA NT WA QLD with ultra low carbon sandy soils that cant protect the topsoil (including the carbon kept within) from disappearing in wind and erosion ?

Adding a plough or legumes to semi arid drought prone sandy soil watch the dust storms… how do you replace millions of tonnes of carbon contained in topsoil at 0.8 tonnes per 10,000m2 ?

Millions of hectares of sandy soils need complete rest in drought and in low rainfall seasons ploughing and or overgrazing these fragile soils compound the loss of carbon to points of no return.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2009_Australian_dust_storm

Just one WTF flux tower at $150,000 might have been granted to a farmer or grazier so they might totally rest their dry soil for 18 months in a dry year… and let nature do what nature does (regenerate itself).

As for measuring the air…WTF the carbon evidence from grazing is in the soil this is nonsense and a complete waste of $150,000 and the excess carbon required to build install and monitor same over a end life of 15 years or less ?

The real issue here is that in my opinion, buffel grass is a WEED that causes out of control fires ( carbon lost to the atmosphere)

A 2020 study found the threat buffel grass poses to biodiversity equals that of feral cats and foxes. As well as threatening native species, it increases Australia’s risk of fire and impacts Aboriginal culture.

What do the 1000s of acres of solar panels do to the carbon equation