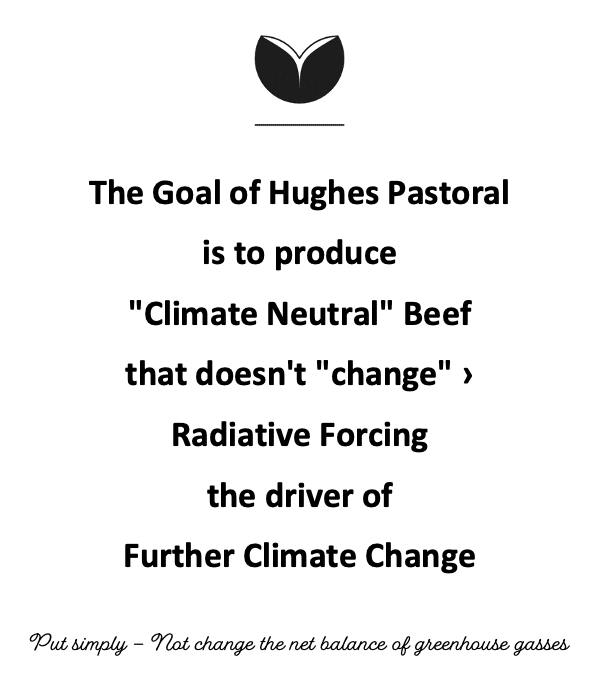

The goal of Hughes Pastoral is to produce “Climate Neutral” beef

Well before methane became headline news with Australia signing the Global Methane Pledge, the Hughes Pastoral Group, who are one of Australia’s largest cattle producers, had already done their homework and realised that their goal should be Climate Neutral. They see this goal as consistent with how the natural world functions.

Peter and Jane Hughes say that they have always concentrated on identifying the basics that you need to get right in each aspect of your business, because if you don’t get the basics right, then everything is not going to fall into place the way it should.

When it came to investigating the true impact of their beef operation on climate change, they quickly realised that if they were to support the global effort to stabilise the climate and stop any further warming, then their operation needed to not be adding to an increase in “radiative forcing”. This is because increasing radiative forcing is the basic driver of climate change. Radiative forcing of each greenhouse gas is known and is measured in watts per cubic metre.

Goal statement in the Hughes Pastral Group land management manual

The Paris Agreement in 2015 stated that its goal was to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees, preferably to 1.5 degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. When talking about the need to achieve this long-term temperature goal, the Paris agreement made reference to achieving a climate neutral world by mid-century. Somehow, the goal has now become Carbon Neutral, when the goal was Climate Neutral with the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement.

Pictured here and at top of page, Peter and Jane Hughes with Hughes Pastoral Group employees at Tierawoomba during a two-day Bushman’s Carnival (campdrafting, bending race etc), a popular annual gathering where all employees from across the group’s properties have the chance to catch up.

When it comes to climate stabilisation (Climate Neutral), climate scientists have long understood that using the GWP 100 metric, for calculating the contribution to temperature change by the different greenhouse gases, is not fit for purpose. Carbon Neutral is based on GWP100 which is using accepted science in a context that no longer applies.

Stabilising the climate (Climate Neutral) relies on stabilising the total radiative forcing of all the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

There are two broad classes of emissions:

- Long-lived greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide, which persist in the atmosphere and build up over centuries.

- Short-lived greenhouse gases, like methane, which disappear within about 12 years. These short-term gases are sometimes referred to as short-lived climate pollutants (SLCPs).

The difference in outcome between Climate Neutral and Carbon Neutral comes down to how short-term gases like methane are treated.

The problem with GWP100 is how it compares these long-term and short-term gases in relation to climate stabilisation. With methane, the GWP100 metric is producing incorrect results in terms of the change to radiative forcing with ongoing stable methane emissions from ruminant livestock. To highlight the point, GWP100 says that a reduction in ongoing stable methane emissions from cattle will still result in temperature rise, when this action actually produces global cooling. The global cooling is caused by a reduction in radiative forcing. GWP* was developed recently to address these shortcomings.

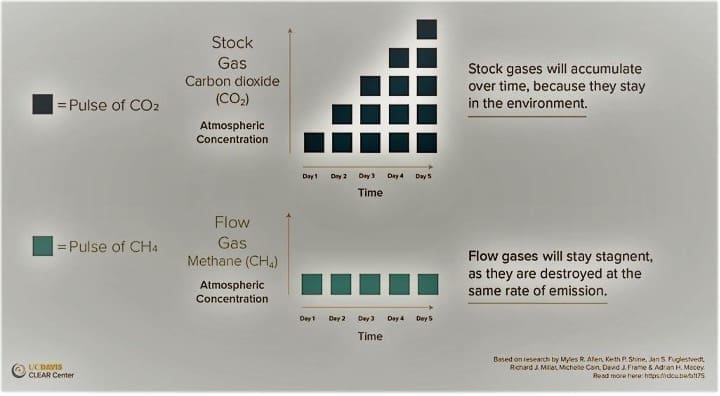

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a stock gas while methane (CH4) is a flow gas

The discussion that follows will demonstrate that methane from ruminant livestock is a flow gas and does not accumulate in the atmosphere; in contrast CO2 emitted from fossil fuels is a stock gas and accumulates. When the goal is Climate Neutral, GWP100 is not fit for purpose because it treats methane as a stock gas – when it is not accumulating.

Methane from ruminant livestock is a flow gas and does not accumulate in the atmosphere; in contrast CO2 emitted from fossil fuels is a stock gas and accumulates. Source: UC Davis CLEAR Centre.

In the graph, Pulse refers a one-off release into the atmosphere. Ongoing pulses of carbon dioxide further changes the climate, while ongoing pulses of methane consistent with previous years, does not further change the climate and is consistent with the goal of Climate Neutral.

The outcome of using flawed accounting for temperature change, is that it changes the emphasis placed on each of the greenhouse gases with policy settings. This results in decisions that move the world towards 2 degrees of warming faster. In the case where cattle methane emissions are stable (not growing over time), using methane reductions as an alternative to CO2 reductions has long term detrimental consequences. It is not in the best interests of humanity, because the remaining budget of radiative forcing available before 2 degrees of warming is reached, will be depleted faster as a result of allowing higher CO2 emissions.

The outcome of using flawed accounting for temperature change, is that it changes the emphasis placed on each of the greenhouse gases with policy settings. This results in decisions that move the world towards 2 degrees of warming faster. In the case where cattle methane emissions are stable (not growing over time), using methane reductions as an alternative to CO2 reductions has long term detrimental consequences. It is not in the best interests of humanity, because the remaining budget of radiative forcing available before 2 degrees of warming is reached, will be depleted faster as a result of allowing higher CO2 emissions.

Even when methane emissions from cattle are stable, it is still important to reduce them where possible, as this increases the available radiative forcing budget to postpone the arrival of 2 degrees warming. This is where Hughes Pastoral see themselves as potentially part of the solution to climate change and not part of the problem. They understand that management that increases carbon flows through the paddock provides a more digestible diet for the cattle. This is because increasing the flow of carbon through a paddock improves the carbon:nitrogen ratio of the pastures. Improving the diet is central to reducing the amount of methane produced per kg of beef produced.

The GWP100 approach is defined for one-off emissions

The GWP100 approach focuses on one-off emissions and compares a one-off emission of methane to a one-off emission of carbon dioxide. GWP100 is emission equivalence accounting, where all greenhouse gases are quantified in terms of CO2 equivalence, termed CO2-e emissions.

The GWP100 has become a default climate metric. Its introduction by IPCC was originally intended to illustrate the difficulties and limitations of any metric designed to aggregate the climate impacts of CO2 and non-CO2 greenhouse gases.

In 2013, the peer reviewed paper “Offsetting methane emissions – An alternative to emission equivalence metrics” (Lauder et al) was published in the “International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control”.

The Abstract states:

We argue that a more appropriate way to consider the relationship between the warming effects of methane and carbon dioxide is to define a ‘mixed metric’ that compares ongoing methane emissions (or reductions) to one-off emissions (or reductions) of carbon dioxide. Quantifying this approach, we propose that a one-off sequestration of 1 t of carbon would offset an ongoing methane emission in the range 0.90–1.05 kg CH4 per year. Our analysis is consistent with other approaches to addressing the criticisms of GWP-based emission equivalence.

The offset equation is very relevant to a producer who wants to increase cattle numbers (increase ongoing methane emissions) and still be climate neutral.

If producers want to increase cattle numbers over the long-term average, then they have to store carbon in the paddock to offset the increased ongoing methane emissions (increased radiative forcing) and still be Climate Neutral.

With the offset equation, the carbon has to be sequestered (stored) in the paddock over a 40-year period.

The paper highlights that with ruminant livestock methane, a steady emissions profile over time can be consistent with climate stabilization.

IPCC acknowledges there are alternatives to GWP100

The IPCC has long acknowledged that there are alternatives to GWP100. The most recent IPCC Assessment (IPCC AR6 WGI, Chapter 7, page 122) states:

“Global surface temperature changes following a pulse of CO2 emissions are roughly constant in time whereas the temperature change following a pulse of short- lived greenhouse gas emissions declines with time. In contrast to a one-off pulse, a step change in short-lived greenhouse gas emissions that is maintained indefinitely causes a concentration increase that eventually equilibrates to a steady state in a way that is more comparable to a pulse of CO2. Similarly, the resulting change in global surface temperature from a step change in short-lived greenhouse gases (Figure 7.21a) after a few decades increases only slowly (due to accumulation of heat in the deep ocean) and hence its effects are more similar to a pulse of CO2 (Smith et al 2012; Lauder et al 2013; Allen et al 2016, 2018b).”

Atmospheric scientist’s summary

“Given that CO2 persists in the atmosphere over centuries to millennia and hence accumulates over time, net CO2 emissions must drop to zero for temperature to stabilize, and additional warming will occur until that condition is reached. By contrast, CH4 has an atmospheric lifetime of approximately 12 years and emissions do not accumulate over centuries; hence, even a very moderate reduction of global CH4 emissions at a rate of about 0.3% per year would stabilize warming from CH4 at approximately current levels. These different temperature outcomes have led some authors to argue that expressing CH4 emissions as ‘CO2-equivalent’ emissions based on the common 100-year Global Warming Potential (GWP100) is misleading and dangerous as it could misdirect attention from the need to reduce global net CO2 emissions to zero as quickly as possible. These concerns have led some to maintain that deep reductions of agricultural CH4 emissions are not necessary to support ambitious climate action. This view is further supported by an interpretation that slowly declining CH4 emissions already represent climate neutrality, given that this would not result in additional warming compared to the present.

While the need to reduce the dominant, long-lived greenhouse gas CO2 to zero is unambiguous, the same does not apply to CH4, owing to the different lifetimes of these gases and temperature response to their emissions.” (Reisinger)

See more: The true goal is Climate Neutral not Carbon Neutral (Word Document – Pages 23 – 29 of the Hughes Management Manual)

The difference between fossil methane and cattle methane

Methane lasts 12 years in the atmosphere (some suggest shorter), before being broken down into CO2 and H2O. It is broken down by a chemical reaction with hydroxyl radicals (OH) that keep forming in the atmosphere.

Fossil methane is different to cattle methane in terms of climate change. When fossil methane breaks down in the atmosphere, it adds a new carbon atom (in the form of CO2) to the atmosphere that was not there before. This is not the case with cattle methane, that on its breakdown, is just replacing the carbon atom that came down as CO2 during photosynthesis and found its way into a cow.

The IPCC recognises this point and in reports, the GWP for fossil methane is one more than agricultural methane i.e., fossil methane is adding a new CO2 molecule to the atmosphere while cattle methane is not.

The subtly here is that fossil methane, even if constant from one year to the next, is increasing radiative forcing, because of the new carbon atom constantly being added to the atmosphere.

Changing from grazing to cropping does have a greenhouse price

It is often suggested that we need to shift to a plant-based diet to stabilise the climate. However, this is simplistic, and overlooks the need to consider changes in soil carbon levels with the shift from grazing to cropping. “A second challenge is that soil carbon stocks under pastures are generally high, and shifts to cropland result in a period of CO2 emissions.” (Reisinger).

Another case of focusing on the basics

Another example of Hughes Pastoral getting back to basics, is their seeing “carbon flows” as the true driver of natural capital, which is a topic gaining momentum. Put simply, natural capital is the measurement of the assets, while carbon flows are the enabler to increase natural capital.

Conclusion

The concept of CO2-e emissions based on GWP100 is deeply embedded in climate policy despite long-standing criticism of its application to SLCPs like methane.

Carbon neutral is based on CO2-e defined in terms of GWP100 which gives a poor indicator of what is required to achieve temperature stabilisation.

Any ongoing releases of CO2 are continually increasing the radiative imbalance of the atmosphere, while ongoing releases of cattle methane at a constant level leave the balance unchanged.

Under GWP100, using methane reductions as an alternative to CO2 reductions is a quick fix with long term detrimental consequences. In 2000 Jim Hansen suggested that reducing CH4 quickly is a useful thing to do IF (and by implication ONLY IF) you stop the growth in CO2 emissions.

In terms of climate change, if methane from cattle is capped at today’s rate, this is basically the same as cutting CO2 emissions to zero.

Climate neutral, as expressed through metrics such as GWP*, captures the actual changes in the radiative forcing that drives climate change.