Dry ageing cabinet featuring in Woolworths flagship Indooroopilly QLD store

TASTE panel sensory work in Australia and Japan has for the first time indicated a clear consumer preference for dry-aged beef over conventional vacuum-packaged ‘wet-aged’ product.

Debate has raged for some time over whether dry-ageing delivers any clear benefit in flavour and tenderness over conventionally-managed beef, and this project – perhaps for the first time – suggests that there is foundation behind such claims.

Dry-aging* cabinets have become a familiar feature in many premium steak restaurants and artisan retail butcheries, but some suggest they are more of a ‘feature statement’ or ‘talking-point’ than providing any real eating quality advantage.

Although there have been earlier studies on the effects of dry ageing on eating quality of beef, no previous research has compared the results of wet versus dry-ageing.

Collaborators on the project, ‘Dry ageing of Australian beef for Japanese and Australian markets’, included meat scientists Dr Robyn Warner from University of Melbourne, Dr Peter McGilchrist from University of New England, Minh Ha, Steve Bonney, Joanne Gallateley, Rod Polkinghorne and Long Huynh.

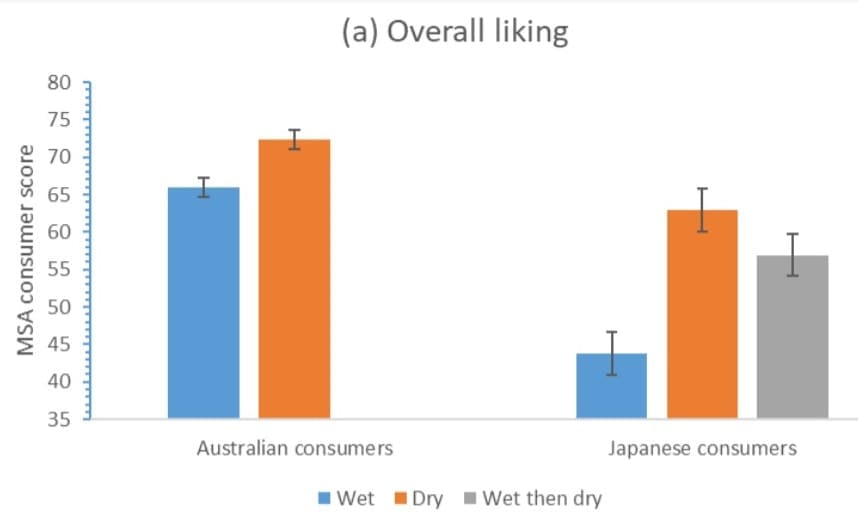

As illustrated in the graphs below, consumers in both Australia and Japan showed clear preferences in sensory taste panel tests for dry-aged beef, with Japanese consumers showing the strongest preference.

Market acceptance in Japan

Imported Australian beef destined to be dry-aged in Japan is usually wet-aged in cryovac form during sea shipment from Australia, and then opened and dry-aged for a further period after arrival in Japan.

Recently, the US has been competing with Australia in this specialised market segment, and has attempted to position dry-aged beef as only being ‘authentic’ and ‘premium’ if it is continuously aged in air. Some US imported beef, often bone-in items, are air-freighted into Japan, and then dry-aged without the wet-age component.

As a result, one of the objectives of the research project was to investigate the effect of dry-ageing and a wet-then-dry ageing process, on eating quality, flavour chemistry and yield of Australian beef. Both were compared with traditional vacuum-packaged wet-ageing. MSA consumer panels were run in both Australia and Japan to make the comparisons.

Striploins and cube rolls were collected from 24 Australian beef carcases eligible for MSA grading (AusMeat colour scores 2-3; ultimate pH less than 5.7, fat cover greater than 3 mm).

Portions from each primal were allocated one of three groups:

- Wet-ageing (boneless) for eight weeks

- Dry-ageing (bone-in) for eight weeks, or

- Wet ageing bone-in, for three weeks, followed by dry-ageing for five weeks (wet-then-dry).

All ageing treatments were allocated within a carcase and the treatments were rotated in their position in the striploin and cube roll. All ageing was conducted at a commercial facility which was export accredited.

Australian and Japanese consumer sensory results obtained using MSA protocols showed that:

- Dry-aged beef loins were scored higher than wet aged products, with eight-week dry-aged products receiving optimal scores compared to eight-week wet-aged product.

- The higher scores for dry-aged products were consistent in all sensory parameters including tenderness, juiciness, flavour, and overall liking (Figure 1).

- Japanese consumer data also supported the superior eating quality of dry-aged beef loins compared to the wet-aged equivalent.

- Sensory results using Japanese consumer panels showed that the wet-then-dry treatment resulted in products with similar sensory qualities compared to the dry-aged (only) products, and superior compared to the wet-aged (only) products. This finding supported the view that Australian exports to Japan in vacuum-packed form are at no great disadvantage to US dry-aged product, in terms of eating quality, when aged dry for a further five weeks.

Effect of ageing method (wet, dry, wet-then-dry) for eight weeks on eating quality scores given by consumer panels conducted in Japan and in Australia

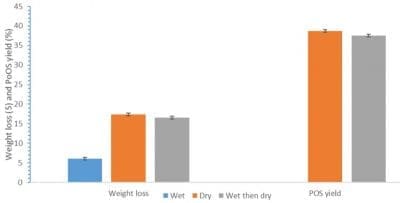

Weight loss comparisons

Weight loss after eight weeks ageing was similar for both dry-aged and wet-then-dry aged products, and higher then wet-aged products. When comparing product at eight weeks that had been only dry-aged to product undergoing wet-then-dry ageing, there was no difference in point of sale yield, after boning and trimming.

Effect of ageing method (wet, dry, wet-then-dry) for 8 weeks on weight loss (%, between weeks 1 and 8) and ‘point of sale’ (POS) yield (%, from bone-in week 1 product to boned, trimmed steaks at week 8)

Results showed wet-aged striploins in the trial lost about 5pc in weight during the eight-week ageing process, while dry-aged and wet/dry aged samples lost 17-16pc.

Due to shrinkage during dry-ageing, changes in fat texture and the colour of lean and fat tissue, the project recommended sufficient fat cover (at least 20 mm) on beef cuts to maximise yield at point of sale. In addition, dry-aged products were more susceptible to spoilage due to bacterial growth, meaning high hygiene standards pre-ageing (during quartering and boning) were particularly important for products destined for dry-ageing, the project report said.

“Beef primals exported in vacuum bags (wet-aged) prior to dry-ageing is possible, but require more stringent hygiene and process control,” the report said.

A higher air-speed in the chamber at the start of the dry-ageing period was recommended to accelerate drying, followed by a lower air-speed towards the end to reduce yield loss.

Dry-ageing ‘boom’ in Japan

Alongside the spread of Western steakhouse restaurants (see earlier Beef Central report), there has been something of a dry-aging ‘boom’ in Japan, MLA’s Tokyo-based regional manager Andrew Cox told Beef Central this morning.

“Most dry-aged beef here is domestic Japanese in origin, because many believe ‘true’ dry-aging means always dry, never wet-aged,” Mr Cox said.

Usually leaner beef types like Holstein or Red Wagyu were used. Black Wagyu beef was considered to contain too much fat to be suitable for dry-ageing.

“There is some Australian and US imported beef dry-aged here too,” Mr Cox said.

Explaining some of the design of the research project, he said Australian product would typically be shipped in vacuum-pack (wet-aged) form, and then opened and further dry-aged by the Japanese wholesaler.

Some US imported beef including items like whole t-bones were air-freighted, and then dry-aged without the wet-age component.

In that area, the US had an advantage in Japan, due to cheaper air freight, as well as the fact that many Japanese saw dry-aging as a US trend, Mr Cox said.

There were no clear definitions for dry-aging in Japan, and a recent food safety warning put out by the Japanese health ministry had meant some restaurants and consumers might be hesitating over seeking out dry-aged products.

* What is dry ageing?

Dry aging involves the drying and dehydration of quarters or whole beef primals in a low-humidity, temperature controlled chilled environment for extended periods. The process changes beef by two means: moisture is evaporated from the surface of the muscle, with the resulting process of desiccation creating a greater concentration of beef flavour; and secondly, the beef’s natural enzymes break down the connective tissue in the muscle, leading to tenderisation.

The process of dry-aging can also promote growth of certain fungal (mould) species on the external surface of the meat. This does not cause spoilage, but rather forms an external ‘crust’ on the meat’s surface, which is trimmed off when the meat is prepared for cooking. These fungal species complement the natural enzymes in the beef by helping to tenderise and increase the flavour of the meat. The fungi genus Thamnidium, in particular, is known to produce collagenolytic enzymes which contribute to the tenderness and flavour of dry-aged meat.

Downsides with dry-ageing include the time required (up to 60 days is common) and a considerable weight loss in cuts (20-35pc) due to the dehydration process. Finished items also need to be larder-trimmed to remove the surface ‘crust’ that forms.