This is the first in a series of articles appearing on Beef Central in coming weeks marking the 20th anniversary of the start of the Meat Standards Australia program, launched in 1998. Today’s article looks at the mood for change that emerged across the industry in the early 1990s in the need to address product quality issues, and the groundbreaking research that led to the formation of today’s MSA…

Pictured during the formation of the MSA steering committee in 1996 were chairman, David Crombie, second from left, with lotfeeder Dugald Cameron, AMLC program manager John Webster, and Woolworths’ Phil Morley. Click on image for a larger view.

THE ideal of trying to identify beef product quality is almost as old as the Australian beef industry itself.

At least as early as the 1930s, crude grading systems based on little more than carcase weight and dentition were applied as colour strip carcase brands at abattoirs in Queensland and some other states, without gaining significant consumer or trade support.

During the 1980s, lotfeeders started pushing for grading development, without having a clear idea of what was required to deliver it. Members of the still emerging Australian Lot Feeders Association were convinced that grainfed beef was better and more consistent than other alternatives, and that it needed to be identified and acknowledged, so that it could be priced accordingly.

During the 1980s, lotfeeders started pushing for grading development, without having a clear idea of what was required to deliver it. Members of the still emerging Australian Lot Feeders Association were convinced that grainfed beef was better and more consistent than other alternatives, and that it needed to be identified and acknowledged, so that it could be priced accordingly.

While this push to develop a grading system gained momentum, there was often an equally large opposition to the process from other segments of the beef industry.

Some stakeholders felt that while 95CL beef (95pc lean meat/5pc fat) was perfect for hamburgers, it should be ‘downgraded’. Others argued that it was inappropriate to describe such a product as sub-standard or third-grade, when in fact it was ‘first grade’ for what it was intended for – grinding.

The establishment of AusMeat in 1985 was heavily supported by the lotfeeding sector, which quickly seized on the potential of the AusMeat language to drive product description, and potentially, branding.

For the first time the potential existed to move from defining meat simply as first, second or third grade, instead using a set of relevant parameters that could let the industry accurately and appropriately describe a product to suit any particular customer.

Early initiatives driven by lotfeedeers

It was an ALFA initiative in early 1991 that ultimately led to what the Australian red meat industry now knows as Meat Standards Australia.

Former ALFA president Rod Polkinghorne provided his impressions and recollections of the circumstances that led to the creation of MSA during a presentation at a BeefWorks forum in Toowoomba in 2011.

Rod is widely regarded as one of the forefathers of MSA in terms of its commercial pathways development.

The primary concern within lotfeeding ranks at the time was the need to control domestic grade standards, and the development of an ALFA-backed quality beef brand was seen as the best way to achieve that.

Following some ‘fairly primitive’ taste-test trials, ALFA commissioned a consumer research project to ascertain consumer reaction to a range of grainfed branding propositions.

The brand name, ‘Tender Choice’ was selected as a result of this work and plans were formulated to launch nationally following a three-month trial in Woolworths’ Gold Coast stores in mid-1992. While consumer reaction to the product was good, brand recognition was poor.

ALFA then took a more structured approach to the grading challenge, forming a company called Australian Meat Standards, which had the objective of establishing an independent Australian quality grading system to cover the full range of grainfed beef produced for domestic and export markets.

“Almost as an afterthought we decided to run some consumer tests to resolve the grade question,” Rod Polkinghorne said.

In 1992 the Meat Research Corporation* (*the industry’s research and development company, that operated in parallel with the Australian Meat & Livestock Corporation, before being merged to form Meat & Livestock Australia in 1997) had commissioned a number of studies in domestic and export markets to delve into the reasons for a steady decline in beef consumption and price.

The same year the first Beef Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) was established, led by an infectiously enthusiastic Dr Bernie Bindon, with improved eating quality defined as the central objective.

This, and subsequent CRCs II and III, drove much of the important, exhaustive meat science discovery necessary to deliver the modern day Meat Standards Australia grading system.

First serious consumer tests

With MRC and Federal Government support, the first serious consumer tests were conducted in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane later that year, on a range of different product.

The results gave researchers plenty to think about.

On raw appearance, domestic Australian consumers hated any sign of marbling or external fat. The more marbled the product, the more they rated it as ‘unhealthy’, regardless of external trim, and the worse they thought it would eat. When eaten in blind taste tests, however, the results were the exact opposite: the high marbling product scored best.

Adding to this consumer perception was an AMLC marketing campaign of the era advocating and promoting absolute ‘leanness’ in beef as a desirable quality. This made it difficult to convince consumers of the merits of marbled beef and its consequent eating quality when appraised in its raw state. The problem disappeared at the food service level, however, where customers saw the product only in its cooked state.

Consequent meat science research started to unravel some of the mysteries about fat composition, discovering that the fatty acid profiles of the ‘marbling’ fat differed significantly from that contained in sub-cutaneous, or external fat. In fact marbling fat contained less saturated fats, and more ‘desirable’ mono-unsaturated and omega 3 and 6 fats.

Adding to the concerns about consumer preference at the time for leanness, there was little relationship to the AusMeat grading indicators other than that the highly-marbled beef tended to eat better. Even this varied, and the domestic product spanned the full range from dismal failure to premium, despite having identical AusMeat description.

“To overcome the lack of consistency within common AusMeat description, the group hypothesised that we needed to apply a series of standards prior to grading, as it was assumed that there were issues affecting eating quality that we couldn’t see at the point of grading,” Rod Polkinghorne recalled. “This concurred with thinking among researchers in the US and the UK at the time.”

Establishing grade standards

An AMLC-supported trial established in collaboration with Woolworths northern supply chain at Ipswich (Qld) in 1995 established a series of grade standards, with six Woolworths retail stores receiving the company’s standard product, and another six stores, the graded product.

The grading criteria demanded a maximum of 50 percent Bos Indicus; minimum 70 days on feed; minimum of 100kg weightgain in the feedlot; exclusion of cattle with bad temperament or poor health history; direct consignment to slaughter; electrical stimulation and use of modern chilling systems in the abattoir prior to grading using AusMeat criteria.

This marked the first occasion in which feedlot criteria and abattoir minimum standards, supported by QA documentation, became a formal prerequisite for grading.

Between July and October 1995, 22,591 carcases were assessed under the Woolworths trial, with 2570 accepted into the new ‘Tender Choice’ pilot brand. Due to commercial issues (the name was already owned and trademarked by somebody else), the name ‘Tender Choice’ never made it onto retail shelves, but it was seen in some wholesaler chains supplying higher-end restaurants in the Sydney market.

Random striploin and rump steaks were purchased from the Woolworths stores selling graded product, and those selling standard product. The steaks were served to consumers in Brisbane, amid great industry expectation.

Industry stakeholders were devastated when the results showed no difference in variation in ‘unacceptable’ samples: both groups included a substantial quantity of unsatisfactory product. When repeated two months later, there was still no difference, and the trial was at the point of being abandoned.

“What was wrong? We were using all relevant meat science knowledge from around the world available at that time, and yet we couldn’t guarantee an improved product,” Rod Polkinghorne recalled.

“Did beef just vary? We began to think that at low marbling fat levels like those typically seen in Australian domestic beef, visual carcase appraisal and slaughter floor data could not reliably categorise eating quality,” he said.

Fortunately, researchers gave it one last shot, running a further trial in which this time, different combinations of electrical stimulation and chilling were applied.

A set of startlingly positive results emerged in favour of the graded product, challenging conventional wisdom of the time over the use of electrical stimulation.

It was a turning-point. The outcome proved that, depending on how it was applied, electrical stimulation could both enhance and detract from carcase eating quality. The results formed the basis of the industry’s eventual adoption of MSA’s critically-important abattoir pH/temperature window, a process now widely adopted around the world.

Key questions for meat scientists

For the Beef CRC team responsible for the development of MSA pathways in the mid-1990s, there were two key questions:

- Did consumers have a consistent view of quality?

- If so, could a commercial means be devised to identify quality levels prior to consumption?

“The issue of using consumers in evaluation led to considerable robust discussion around the industry,” Rod Polkinghorne recalls.

“Many believed that consumers were so variable and inconsistent in their views that they could not be used to obtain reliable answers.”

Certainly it was found that consumer results were often erratic, but often for good reasons: two well-done steaks might receive different responses from individuals who preferred meat rare versus well done; while a terrible steak served after an excellent steak might be rated differently than when served in reverse order.

However a series of important interventions were introduced which saw consumer scores became both ‘sensible’ and ‘repeatable’. Consumer taste test results suddenly became a wonderful scientific instrument, which was to become the central pillar of MSA.

More on that in an upcoming story in this series.

“Everything could be indexed against the end-consumer; the grading standard could be solely defined as a consumer score without any other reference; for example a score above 77 MQ4 points graded 5-star, 48 points graded 3-star, and so on,” Rod Polkinghorne said. An MQ4 score is a single meat quality score based on MSA criteria assigned to each cut, by use.

Pathways approach

These standards were applied to what quickly became known as MSA pathways. A pathway represented a number of criteria which all had to be met or exceeded, in order for the beef to be accepted.

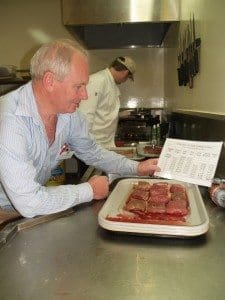

Rod Polkinghorne prepares samples used in one of thousands of MSA taste panel tests around Australia over the past 20 years

Striploin steaks from cattle meeting those criteria were tested, and exceeded the minimum consumer criteria allowing the pathway to be approved. This allowed striploin, tenderloin and rib eye steaks to be labelled ‘3-star’, under the emerging system. No other cuts or cooking methods were approved at that time.

Early market survey work in Brisbane was conducted to benchmark product supplied by major retailers under their superior quality categories. Of ten groups tested, eight failed to meet the 3-star pathway standard, indicating the size of the challenge that lay ahead.

“Soon, other pathways were explored, for different combinations,” Rod Polkinghorne recalled.

“How about 50pc Bos Indicus with tenderstretch and 28 days ageing? The test process would be repeated and measured over and over again, against the standard. This triggered a lot of useful testing with a great deal of knowledge gained about tenderstretching, ageing, electrical stimulation, use of growth promotants and chilling regimes – all being put to the consumer test,” he said.

While much of the science was known, the consumer relationship provided new insights and understanding of the mechanisms, as well as quantifying the impact.

A level of success was achieved under the pathways approach when a single grilled striploin result was the measure. A sufficiently tight set of pathway parameters could be used to deliver an acceptable level of consumer satisfaction.

A major problem, however, was that as the pathway criteria were strengthened to achieve acceptable levels of consumer guarantee, many rejected cuts actually performed well. But conversely, if criteria were relaxed to achieve an acceptable level of inclusion, the failure rate became unacceptable.

“The reason was that individual inputs interacted, so that a minimal failure in marbling level might be offset by lower ossification or longer cut ageing, for example, Mr Polkinghorne said.

To address these issues, multiple alternate pathways were devised and tested, each delivering a common designated quality result.

This became difficult to manage, however, and as individual cut and cooking method testing commenced, completely unworkable due to the countless possible combinations and their different outcomes at the cut level.

Researchers began asking questions about other cuts and other cooking methods, in order to extend grading to more of the carcase.

Relativity between cuts in a carcase

A major challenge arose when it was proved that there was little relativity in tenderness between cuts within the same carcase.

Whereas conventional US-style grading assigned a grade to a whole carcase, Australian trial results proved conclusively that this could not deliver an acceptable consumer result. The inherent assumption that if something like a USDA grade was assigned to the striploin, then other cuts could be accurately estimated from it, proved false.

Different characteristics including sex, weight, ossification, breed, carcase hanging method, ageing time and other criteria could affect these relationships between muscles.

Tenderstretch carcase hanging, for example, had a big effect on some muscles and none on others. In fact in some cuts, like tenderloins, it had a detrimental effect.

Ageing effects differ between muscles as does the influence of marbling and ossification. This did not mean that each muscle needed to be individually assessed in a grading process, but rather that a single set of carcase-based inputs – such as carcase weight, sex and marbling – needed to be applied with differential weightings for each muscle.

Fortunately, accounting for these variables was not difficult within a computerised system – still a novel use of the technology at this time.

Pursuing eating quality on a ‘coordinated’ basis

Around 1996, ALFA, the AMLC, MRC and other stakeholders started working collaboratively to pursue eating quality on a more coordinated basis.

Much of the important early exploratory work carried out under ALFA’s flag was generously handed over to the collaborative industry group, with the science led by Dr John Thompson, head of Meat Science at the University of New England. Dr Thompson made a major contribution to MSA’s progression, serving throughout the entire three-term CRC I-III period, which concluded in 2012.

A second critical foundation of today’s MSA program has proved to be the compilation of a single database incorporating all results rather than holding individual trial results separately.

The modern MSA database contains more than 50,000 cuts, with all available associated data held in 140 columns for each. This provides a powerful tool from which relationships can be established from a consumer-down perspective.

Consumer scores are used to establish the MQ4 weightings (and today’s MSA index scores) and grade cut-offs for each cut. All potential grading inputs were then considered and combined where useful to predict the observed MQ4 or its successor, the index score.

MSA grading model’s ‘lightbulb’ moment

Use of this principle led to the third central pillar of today’s MSA program – the MSA grading model.

“This was the real light bulb moment for MSA,” Rod Polkinghorne said.

“By estimating the MQ4 score for each muscle and cooking method combination, the individual inputs could be handled differently and interactively. Rather than using the pathway approach of having to meet a series of rigid parameters, a high performance in one attribute could offset a lower result in another. The complexity of managing an increasing number of alternate pathways, most likely specific to individual cuts, could be replaced by a single interactive model.”

Importantly, accuracy could be improved while false rejections could be reduced; most of the acceptable product was graded and most of the unsatisfactory product rejected. From that point forward, MSA could become a commercial system.

In 1996, an MSA steering committee was formed, chaired by respected beef agribusiness identity David Crombie. Mr Crombie was later to serve as an MLA chairman and president of the National Farmers Federation.

Although he had had only a relatively low industry ‘profile’ up to that point, he proved an inspired choice to drive the emerging MSA project project forward, combining boundless energy, a gift for communication across the stakeholder spectrum, and an ability to bring often divergent parties (and there were plenty of them, as will be described in a later story in this series) together to achieve an outcome.

The establishment of this steering committee in itself represented a considerable breakthrough. For the first time, all sectors of the beef industry were represented in a meat science project around a table – northern and southern producers, lotfeeders, processors, supermarket groups and butchers.

With much of the meat science puzzle behind delivering an accurate and repeatable eating outcome starting to be resolved, a target date of March 1997 was set to launch a pilot Eating Quality Assurance (EQA) scheme in the Brisbane market. Significant resources were marshalled to pursue the ideal of identifying beef quality to consumers. For the first time, EQA ads were pushed out in front of the Brisbane public.

In the period prior to the pilot’s launch, the original name, EQA, became Meat Standards Australia. However the original EQA name was to reappear in 2010 as the program’s export market descriptor.

Pilot study work continued in the Southeast Queensland and later, WA consumer markets through late 1997 and into 1998, moving to full commercial roll-out around March. The Certified Australian Angus Beef program became the first branded beef to be underpinned by MSA, processing out of the now defunct Foster meatworks in NSW. MSA was formally launched as a truly national beef tenderness guarantee and grading scheme in July, 1999.

Continual refinement has taken place over the basic MSA model first developed in 1998, with new releases every year improving its scope and accuracy. New inputs such as HGP and further hanging methods have been added; marbling and ossification accuracy have been extended to higher scores, all built on further data arising from consumer testing.

The move from the use of boning groups to an MSA Index was another more recent advance, adopted during early 2014. Trials in Korea, the US, Ireland and Japan added further valuable data and linked results from Australian beef and consumers to those from other countries.

Beef Central will publish a series of further articles in coming weeks marking MSA’s 20th anniversary.

Beef Central will publish a series of further articles in coming weeks marking MSA’s 20th anniversary.- Next: The importance of the ‘Empty Chair’