TWO prominent red meat processors have gone toe-to-toe in the courts over alleged similarities between their beef brands, trademarks and acronyms, and the risk of confusing or misleading customers and consumers.

JBS Australia took Joe Catalfamo’s Australian Meat Group to the Federal Court over alleged similarities between JBS’s well-known ‘AMH’ trademarked label, and the identity and appearance of the Australian Meat Group’s own ‘AMG’ brand.

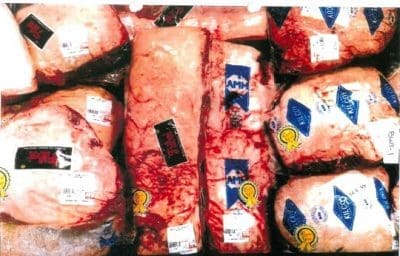

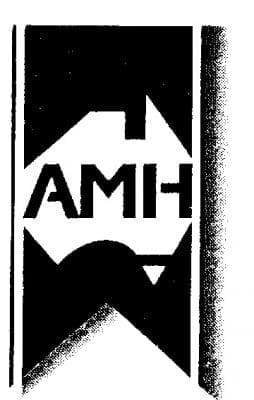

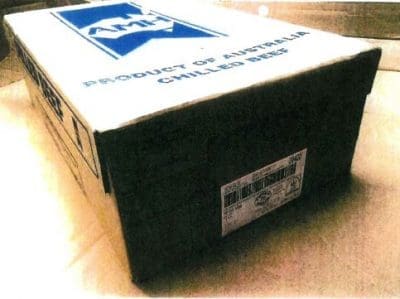

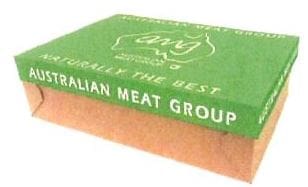

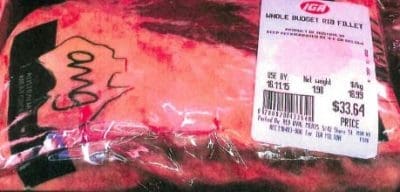

Both the graphic versions of the trademarks (see images published here) use a map of Australia as a background, and use a similar sequence of letters in the acronyms.

Much of the evidence during the three-day hearing focused on intellectual property and the use of trademarks, and the likelihood of consumers and other customers confusing the two images and acronyms.

The original Federal Court hearing before Justice Andrew Greenwood dated back to 2016, but the 287-paragraph judgement was not posted until late last year.

Justice Greenwood found in favour of JBS in the hearing, which has since been appealed by AMG. Costs were reserved for later judgement.

At the heart of the issue, JBS claimed that similarity between its ‘AMH’ and the ‘AMG’ label, as well as the use of the three-letters acronyms, was damaging its business.

To complicate matters, Joe Catalfamo, the principal of AMG, in 2008 sold his Tasman Group southern processing business to JBS Australia for $1.4 billion. As part of the deal, he was placed on a ‘gardening contract’ for several years, before re-emerging with the purchase of the Dandenong processing facility near Melbourne, and the Denilliquin plant just over the NSW border, creating the Australian Meat Group business some years later.

The court hearing was primarily focussed on the question of whether AMG’s trademark was ‘substantially identical’ or ‘deceptively similar’ to JBS’s AMH trade marks.

The original AMH trademark was registered by the original owner, Australia Meat Holdings in 1989. Australian Meat Group registered its device trademark under the ‘meat’ category, when the company was established in 2014.

Both images are widely used on vacuum package plastic bags, and beef carton lids.

The original Australia Meat Holdings (AMH) company name disappeared in 2006, firstly becoming Swift Australia, then bought by the current owner, JBS Australia. However the company’s testimony emphasised that the AMH label and trademark, continues to be used widely by the company.

JBS Australia chief executive Brent Eastwood told the court the ‘AMH Brand’, which he described as the ‘AMH name’ and the device mark (incorporating the acronym AMH) was the longest-standing brand in use among JBS’s stable of brand names.

It always was, and still is the dominant brand used by JBS on its meat products, he said.

JBS marketing executive Brad De Luca told the court the AMH trademark was considered by JBS to be one of the most recognisable and respected beef brands, both in Australia and internationally. He suggested a minimum of 20pc of the carcase beef produced at JBS’s Riverina, Dinmore, Rockhampton, Townsville and Beef City processing facilities was packed into a carton which has a lid, on which the AMH trademark appeared.

Over the eight-year period to 2015, product had been packed into more than 250 million cryovac bags printed with the AMH trademark, and 95 million carton lids bearing the mark had been sold, totalling more than one million tonnes of boneless beef, the court heard.

Mr De Luca suggested about 2.2pc of all beef consumed in Australia was displayed to retail consumers in whole primal form in a retail environment – in the form it leaves the processor. Many og these whole primals bore processor trademark labels.

JBS submitted that there was also a significant reputation in each trademark, in the eyes of members of the supply chain such as wholesalers, retailers and others.

The question of whether that reputation ‘subsists at the functional level of the supply chain’, where a consumer engages with retail sellers of meat (butcher shops, supermarkets) was a matter contested by Australian Meat Group.

JBS submitted that if a person placing the order saw AMG product ‘by itself’, the use of the AMG sign or trademark was deceptively similar to the AMH trademark, because the only difference between the two was that in one case, the acronym ends with ‘H’ which stands for Holdings, and the other, ‘G’ which stands for Group.

JBS submitted that if a person placing the order saw AMG product ‘by itself’, the use of the AMG sign or trademark was deceptively similar to the AMH trademark, because the only difference between the two was that in one case, the acronym ends with ‘H’ which stands for Holdings, and the other, ‘G’ which stands for Group.

The substantial battleground between the parties was whether AMG’s conduct engages use of a deceptively similar sign as a trade mark in respect of the relevant goods, Justice Greenwood said.

As part of its defence, AMG said from 2008 when the Australia Meat Holdings Pty Limited company name ceased to be used, the new owners ceased to promote and emphasise the name ‘Australia Meat Holdings’ or ‘AMH’, or use the AMH device mark in connection with the business’s trade in meat products. The result was that its reputation in AMH and the device mark diminished over time in favour of other brands or names such as ‘Swift’ or ‘JBS’ itself.

AMG suggested to the court there “was no real, tangible danger” of confusion occurring.

AMG suggested to the court there “was no real, tangible danger” of confusion occurring.

Another AMG witness said he had not heard of a customer misunderstanding either the Australian Meat Group name or its abbreviation, AMG, as being somehow associated with the AMH brand or JBS.

AMG maintained that a side-by-side comparison of the device marks or the acronyms AMH and AMG made it clear that they are not substantially identical.

North-South divide

An AMG witness also submitted that AMH had a long association with ‘northern cattle’ which he described as ‘inferior in flavour’, while AMG primarily focussed on southern cattle for the production of meat. He also said that AMH was a brand based in northern Australia (NT and QLD), before it was purchased by JBS. He said that the companies that Mr Catalfamo set up were southern-based companies which focused on Victoria and Tasmania. Because of that differentiation, AMG did not focus on AMH as a brand, and were not worried about competing with them.

Justice Greenwood said regarding the so-called ‘north/south divide’, he accepted that AMG procures livestock for slaughter and processing predominantly in southern Australia and that AMH predominantly procures livestock in northern catchments.

“However, two things should be noted. First, the applicant’s (JBS’s) registrations of its trademarks are national and unqualified. Second, there is some evidence that cattle are acquired by the applicant in Victoria and southern NSW and taken to Dinmore for slaughter. Moreover, the evidence demonstrates that at least to some extent the respondent (AMG) is supplying its primal cuts for sale in Queensland.”

Importance of establishment numbers

An AMG representative suggested its customers made “well informed choices about what product they buy,” reducing risk of confusion.

The witness also placed emphasis on the importance of the AusMeat meat processing establishment numbers (3085 and 2488, in the case of AMG’s two facilities). The establishment number is the unique three-digit number given to each meat processing plant in Australia.

He said that in his experience, export customers wanted to ensure that the standard of processing was of the highest quality.

The establishment number carried the reputation of the quality and consistency of the product coming out of that plant, and since meat is a perishable commodity, quality and consistency is very important, the witness said.

The establishment number carried the reputation of the way the meat is processed in the relevant plant – how it is cut, the cold chain management process used for the product, and the consistency of the application of that process.

Justice Greenwood said in his summary that each witness emphatically said that what matters in making transactional sales in the export and domestic market for beef products across the various functional levels from meat processing to wholesalers, distributors and retailers was the importance of the establishment number for the facility in which the processing had occurred.

“The establishment number was said to be the badge of quality,” Justice Greenwood said.

“The seller is important as an entity but the quality is said to attach to the establishment number because the establishment number conveys standing in relation to cold chain management processes and other aspects of the processing of meat. Great emphasis was placed upon these things to illustrate the proposition that the brand is not the decisive thing which determines choice by a buyer. Choices are overwhelmingly informed, it is said, by the establishment number.”

While he conceded that rigorous, compliant, disciplined cold chain management and supervision of all of the processes undertaken in an accredited meat processing facility were very important matters in meat production, and sent a signal about quality, Justice Greenwood did not accept that these fundamental matters of physical meat production diminished the role that trade marks in the industry have in differentiating goods as a badge of origin of one trader as against another.

“The idea that the establishment number is the pivotal matter of differentiation to the point where the AMG trademarks are so significantly diminished that they do not operate as a badge of origin or that they are not important in transactions and thus, no real tangible danger of deception or confusion arises through their use, in all circumstances, is not correct,” he said.

“The establishment number is, no doubt, important because a seller of beef is supplying a product which has to be handled in facilities which have rigorous standards so that humans do not get sick when they consume the product. Of course, a buyer wants to know the establishment number, and buyers might well come to understand the high standards (or otherwise) deployed in particular facilities with a particular establishment number.

“However, there is no doubt, on the evidence before me, that the respondent is engaged in a field of rivalry with other suppliers at functional levels of the meat industry in which its trademarks are vigorously promoted as a badge of origin of its meat products in market contestable conduct in the domestic and export markets,” Justice Greenwood said.

“I am entirely satisfied that the use by the respondent (AMG) of its trademarks at this functional level of the market represented a finite and non-trivial danger or real and non-trivial likelihood that a number of participants at the wholesale level of the market will necessarily be left in doubt about whether it the meat products of AMG are those of the owner of the AMH trade marks,” Justice Greenwood said.

“I am also satisfied that the use of the trademarks engage infringements of the applicant’s (JBS’s) trademarks. The addition of other words and titles on the boxes and in conjunction with the AMG device mark does not have the effect of distinguishing or differentiating the branding which adopt as an essential feature, the AMH device mark which suffers from the difficulties earlier described in the sense that it reflects the essential features of the AMH device mark.

“Use of these marks is infringing conduct,” he said.