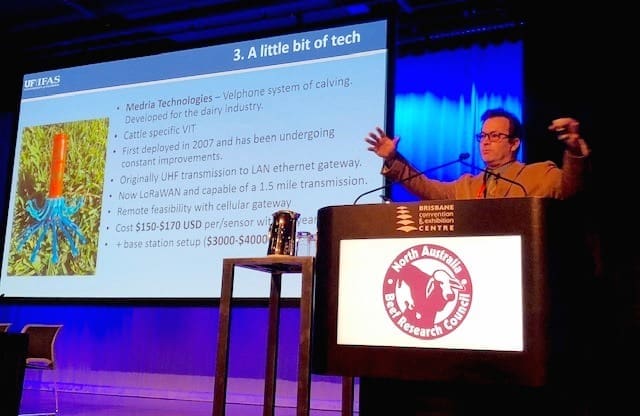

University of Florida rangeland scientist, Dr Raoul Broughton, outlines the Medria Technologies velphone calving sensor system used in research to determine causes of calf loss

TECHNOLOGY is playing a key role in a US livestock research project exploring reasons for calf loss in the sub-tropical Florida region – many of the lessons from which may have application for production systems in northern parts of Australia.

Australian-born University of Florida rangeland scientist, Dr Raoul Broughton, has worked in the Florida environment for the past 20 years. He gave the keynote address at the recent North Australia Beef Research Conference in Brisbane.

Dr Broughton described Florida as an ‘interesting and challenging environment’ for the cattle industry, with obvious parallels in Australia.

Pastures in the region ranged from introduced improved species to native grasses, where stocking rates for a cow/calf pair could be as low as 40 acres (16ha).

While calf survival (measured to day 140) across the entire US beef industry was about 94pc, survival in the Florida region was a lot less, and producers wanted to know why, he said.

“Florida is getting into the sub-tropical region; it is monsoonal like northern Australia with a wet and dry season; and cattle – especially British types – are probably on the extreme of their ability to survive in those habitats,” Dr Broughton said.

It was not only domestic animals that struggled under such conditions. Local white-tailed deer, for example, only produced survival rates in fawns of 30-35pc under the same conditions.

“So beef cattle are doing relatively well – but producers obviously want to do better,” he said.

Dr Broughton said measuring and improving calf survival was integral in an environment like Florida, which was mainly made up of cow/calf operations.

“But it has been one of the hardest areas to monitor and research, because of the high number of logistical issues in the field. There’s a multitude of possible causes of calf loss in the region, which are actually quite difficult to get at.”

This is one of the reasons why suggestions about reasons for calf loss remained quite speculative.

“There are a few occasional big things that occur – maybe some diseases come through, causing a big die-off – but the day-to-day causes of calf loss are quite difficult to get a handle on,” he said.

But being able to identify the causes that most affect calf loss would help focus resources and research to provide the best economic return for local producers, Dr Broughton said.

“An increase of just 1pc survival across the Florida calf herd would be equivalent to 8250 additional calves each year, worth about US$5.5 million. Moving the needle – just a tiny bit – has a big impact, as it does in Australia.”

Dr Broughton started to tease-out some of the particular challenges in the Florida region that contributed to higher calf loss.

To start with, while much of the US beef population was held in very small herds, in more temperate regions, Florida had some of the larger, less intensively-managed herd sizes in the US – up to about 20,000 head.

He made the point that within the 6.4pc national average calf loss to 140 days, almost all of the mortalities happened before three weeks of age – and he suspected the same applied in Australia.

“It’s associated with either bad birth events, weak calves coming out, or potentially other impacts that are going to happen on newborn animals.”

The causes for calf mortality compiled by the US National Statistics Service were grouped into less than, and more than three weeks of age.

This illustrated that some issues, like scours and respiratory problems, were much more common higher in older calves.

“Issues like BRD and pneumonia are big impacts as calves are weaned and transported – they are big deals that we already know about, and there is already a lot of research in this space that absolutely should continue. But what we don’t know is what’s going on in big impacts like birth-related problems and weather-related problems.”

Predation

Beyond that, a 2007-10 US survey suggested 5pc of all calf losses in the US was associated with predators.

“That’s expected to be an under-reporting in some areas, and over the past ten years, there’s been an increase in predator-related deaths in calves. That’s because predator populations are themselves increasing, with the re-introduction of the wolf, now evident right across the US northeast, and both grizzly and black bear populations are increasing.”

In other areas it was the expansion of numbers in predators like the coyote, which have moved into areas they never previously existed in. And coyotes had changed in size and phenotype, becoming much larger and heavier in (20kg in Florida) compared with 12kg in their original home in the midlands, and 35kg in the eastern US.

“There’s a lot of emotion around the impact of predators, but it is probably not where we should be directing our resources”

“So there’s some interesting things going on in wildlife, and calf loss interactions,” Dr Broughton said. “But putting that into perspective, there’s still only a few percent of losses that are related to actual predators.”

The list of predators in Florida credited with calf mortality is surprisingly long: coyotes, mountain lions, wolves, panthers, dogs, bears, bobcats, vultures and ‘other’ predators. Questioned by a conference delegate about alligators, he said unlike Australia’s saltwater crocodile in northern areas, they were responsible for very few calf losses.

But in the context of other calf losses causes, predation was quite low on the list. “There’s a lot of emotion around the impact of predators, but it is probably not where we should be directing our resources, based on these surveys,” he said.

The Florida Cattlemens Association did a calf loss survey in 2008, engaging with ranchers on a ‘proof’ rather than ‘suspicion’ basis, with documentation. Some of the ranchers reported losses of 11pc, and in some individual cases as high as 25pc.

While some of the causes were difficult to follow through, ranches sustaining highest calf loss tended to be in the state’s south, where conditions were more extreme in terms of predator levels, flooding, and temperatures. That survey suggested 60pc of Florida calf loss was occurring within the first ten days of birth.

While about half of respondents saw predators as a problem, how often predation occurred was a different matter, Dr Broughton said.

Technology used to seek answers

In order to better understand what was going on in calf mortality in Florida’s extensive landscape, Dr Broughton’s team looked for technologies that could help, while avoiding human interaction with the herds.

Among the technologies looked at were:

Vaginal implant transmitters, which had in fact been around in different forms for 20 years. The downsides were that they were expensive in larger studies like the one required, and difficult to communicate with over long distances. Cellular or satellite-connected collars could cost $2500 each, making them impossible for studies on the scale required. They had to ability to monitor temperature and movement when ejected.

The Moo-Call calving sensor, designed for use animals in a barn, was not feasible for extensive outdoor use, for up to 90 days, and was cost-prohibitive. Every unit required its own sim-card.

The Australian-developed Taggle technology, using VHF triangulation, which was low energy and cost effective. But the problem was it was not commercially available when the study was launched in 2014.

The final technology looked at, which the study ‘really tested,’ was Medria Technologies velphone sensor system, developed for calving monitoring within the dairy industry using temperature detection. Originally VHF transmission to a LAN Ethernet gateway driven, it became LoRaWAN capable, allowing a 1.5sq mile footprint, which was big enough for Florida. Each unit cost about US$150-$170, plus a base station set-up. Information can be retrieved from the cloud and alerts sent to computers or smartphones.

Dr Broughton said some of this technology was probably now obsolete, being shifted to satellite systems, bit it was all that was available at the time.

“This got us to calves born, in the wild and we knew when it was happening,” he said.

The project’s objective was to conduct the most thorough post-partum calf study every conducted in the region, allowing quantification of causes of calf loss, and establishment of the most common causes.

Using the Velphone vaginal birthing inserts, the project raised some questions about retention of sensors over longer periods, evidence of discomfort or infection and other issues.

While the technology worked quite well in alerting when calving had occurred, temperature changes were much less reliable pre-birth. Occasionally sensors were expelled early (prior to calf birth), and failure rates tended to increase over time.

“What we found was that it works extremely well for the first couple of months, but then starts to decline, in terms of success of sensor and sending signals,” he said.

While no signs of vaginal infection were detected in the original trial, it is now being seen more frequently, with later use.

Equipment design continues to evolve, but the original study achieved success rates in calving alert of 70pc, whioch would not be high enough for most commercial applications, he said.

The original study was conducted on three ranches across Florida in different zones, but further data has been accumulated over time. The study showed a 13.2pc calf loss on average across the three ranges, ranging up to 19.6pc in one example.

Anaplasmosis was found to be very much higher in the southern parts of the state, which was possibly driving through to stress in cattle.

The trial confirmed that most calves were dying within the first day of birth, suggesting dystocia was a big issue.

“The two big things that emerged, that may definitely direct research, were that those early calves, or failure to thrive calves had bacterial infections, and many were septicemic,” Dr Broughton said.

Dystocia was another big problem. On one ranch at least, most of the deaths were associated with large calves, and 130 lb calves were ‘way too big.’

A question from the audience asked about the performance of first-calf heifers in the survey.

The statistics reported in the trial were for mature cows three years and older, but results suggested losses for first and second calf were about double, on average, from palpation to weaning, Dr Broughton said.