FOR a long time emissions from cattle have been lumped in with emissions from other sources as the same destructive forces for the planet in the global climate change narrative.

However, through research overseen by scientists including Dr Frank Mitloehner (right) from the University of California Davis and Dr Myles Allen from Oxford University, scientific consensus is starting to build around the point that livestock-related greenhouse gases are distinctively different from greenhouse gases associated with other sectors of society (more on this below).

However, through research overseen by scientists including Dr Frank Mitloehner (right) from the University of California Davis and Dr Myles Allen from Oxford University, scientific consensus is starting to build around the point that livestock-related greenhouse gases are distinctively different from greenhouse gases associated with other sectors of society (more on this below).

Dr Mitloehner, an internationally recognised air quality expert, explained to the Alltech One virtual conference on Friday night (Australian time) that the concept of accounting for methane according to its Global Warming Potential, as opposed to just its volume of CO2 equivalent, which showed that not all greenhouse gases are created equal, has now made it all the way to the International Panel on Climate Change.

However, despite increasing awareness and understanding at a scientific level, the message has still not been taken up by the mainstream media.

“What I find interesting is that the one missing entity in this whole discussion so far has been the media,” he told Alltech president and CEO Dr Mark Lyons in a live streamed video interview.

“I have not seen any major reporting on this even though it’s such a hot topic.

“I mean, the world talks about what the impact of our food systems are on our environmental footprint.

“Now, this is a major new narrative. And to me, it’s very unusual and it’s very confusing as to why the same outlets that have touted this topic as being so paramount are not talking about these new findings whatsoever.

“So to me that’s problematic. And we have to think about why that is. Have we not explained it right? Is it too early for them to report about it? I don’t know, but this narrative is not going away.

“You will see it will gain momentum, and it will become the new reality.”

Why all greenhouse gases are not created equal

Dr Mitloehner said to date the global climate change debate has tended to focus only on how much greenhouse gases are emitted by different sources.

Most discussion fails to recognise that certain sectors of society, such as forestry and agriculture, also serve as a sink for greenhouse gases.

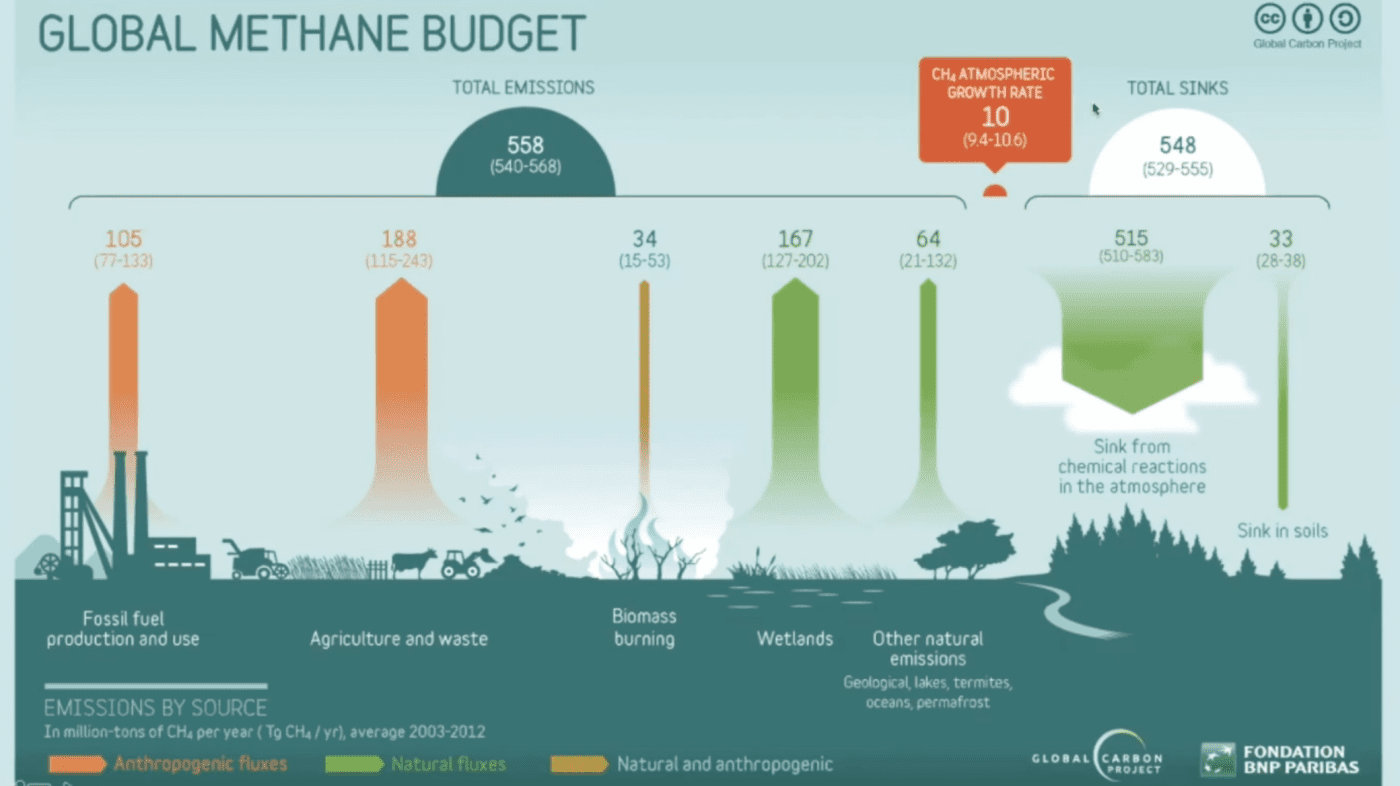

Climate debate focuses on the 560 tera-grams of methane emitted each year but tends to ignore the 550 tera-grams sequested by sinks like agriculture and forestry (right).

After the Kyoto protocol, the climate change debate centred on the 560 tera-grams of methane emitted into the atmosphere each year from all sources, including fossil fuel production and use, agriculture and waste, biomass burning, wetlands and other natural emissions.

“That is where most people stop the discussion, even though they shouldn’t,” he explained.

“Because in addition to emissions putting methane into the atmosphere, we also have sinks on the right side of this graph (above).

“And these sinks amount to a very respectable total number of 550 teragrams.

“So in other words, we have 560 teragrams of methane emitted, meaning put into the atmosphere, but then we have 550 teragrams of methane taken out of the atmosphere.

So in other words, the net emissions per year that we are dealing with is not 560, but it’s actually 10.

“Yet everybody talks about 560.”

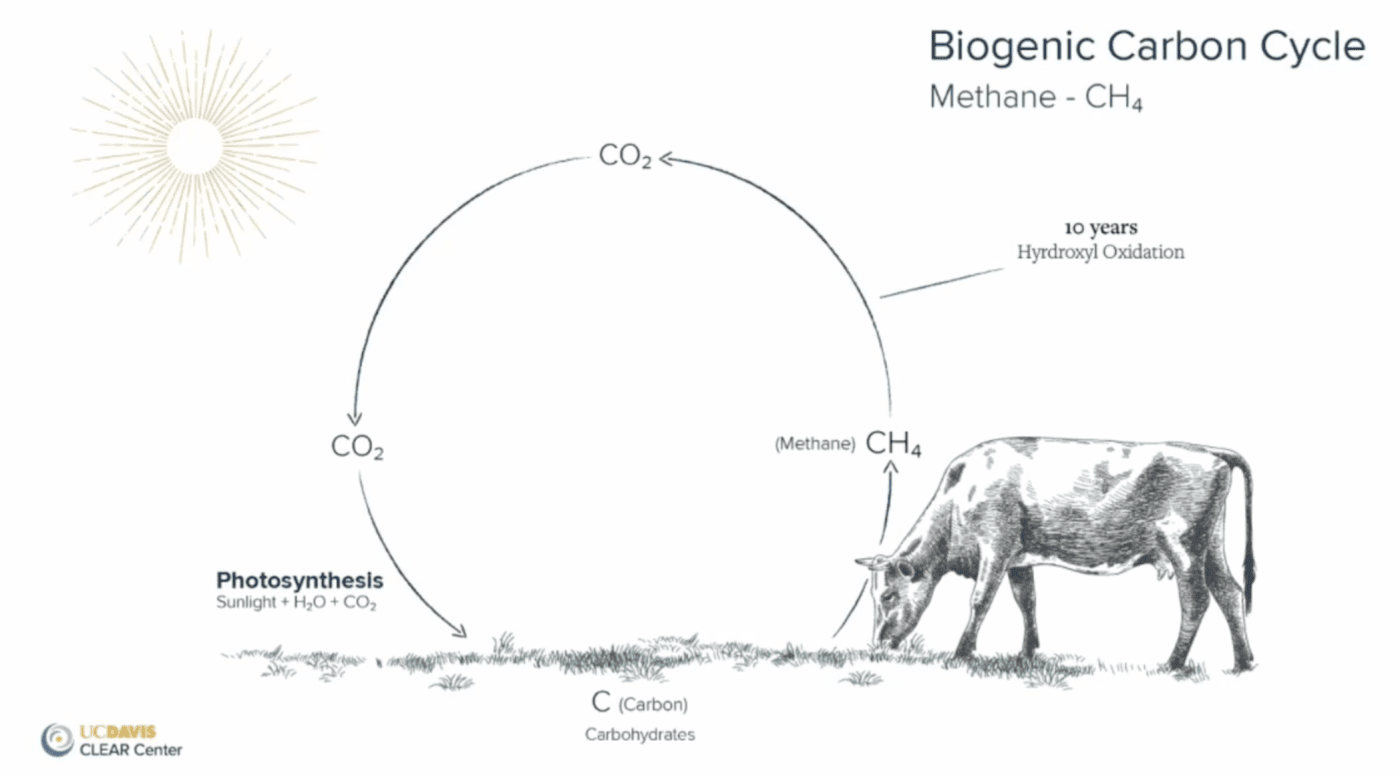

In a biogenic carbon cycle, constant livestock herds or decreasing livestock herds over time did not add additional carbon to the atmosphere, he explained.

The carbon emitted by animals is recycled carbon. It came from atmospheric CO2, captured by plants, eaten by animals and then belched back out into the atmosphere, after a while becoming CO2 again.

Methane is a heat-trapping, potent greenhouse gas, and he stressed he was not suggesting that “it didn’t matter”.

But the key question for livestock is do ruminant herds add to additional methane, meaning additional carbon in the atmosphere which leads to additional warming?

The answer he said was clearly “no”.

Oxford University authors including Professor Myles Allen have shown that biogenic methane is not the same as fossil methane.

It is the same chemically, but the origin and fate “are totally, drastically different”.

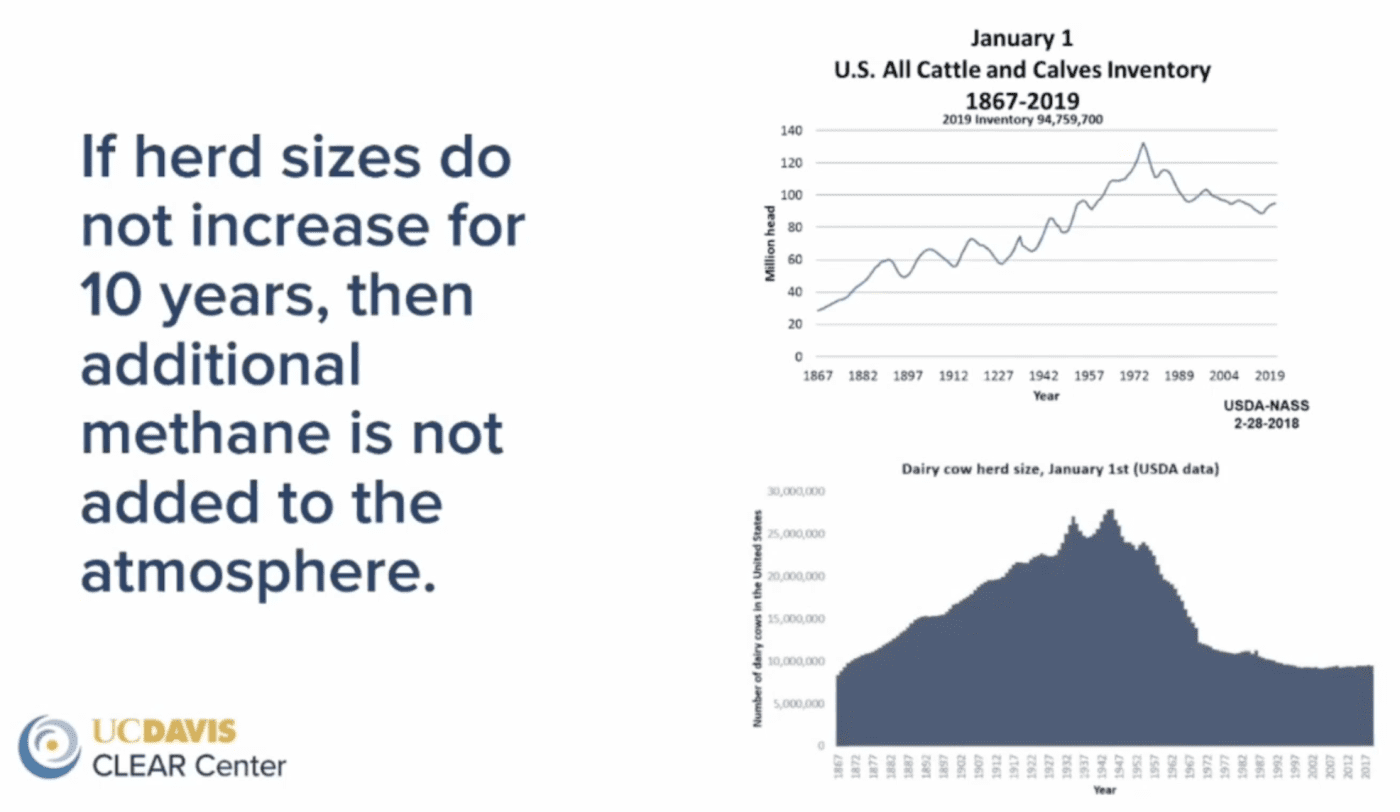

“As long as we have constant herds or even decreasing herds, we are not adding additional methane, and hence not additional warming.

“This is a total change in the narrative around livestock. And I think this will be the narrative in the years to come.”

A chart documenting the size of the US cattle herd since 1867 shows it has decreased to around 90 million beef cattle and 9 million dairy cattle, down from peaks of 140 million beef cattle in the 1950s and 25 million dairy cattle in the 1970s.

The Australian cattle herd has similarly decreased from a peak of over 33 million cattle in 1976 to around 24 million today.

“We’re clearly see a decreasing number of livestock over the last few decades meaning with respect to livestock numbers, we have not cost an increasing amount of carbon in the atmosphere, but indeed we have decreased the amount of carbon we put into the atmosphere,” he said.

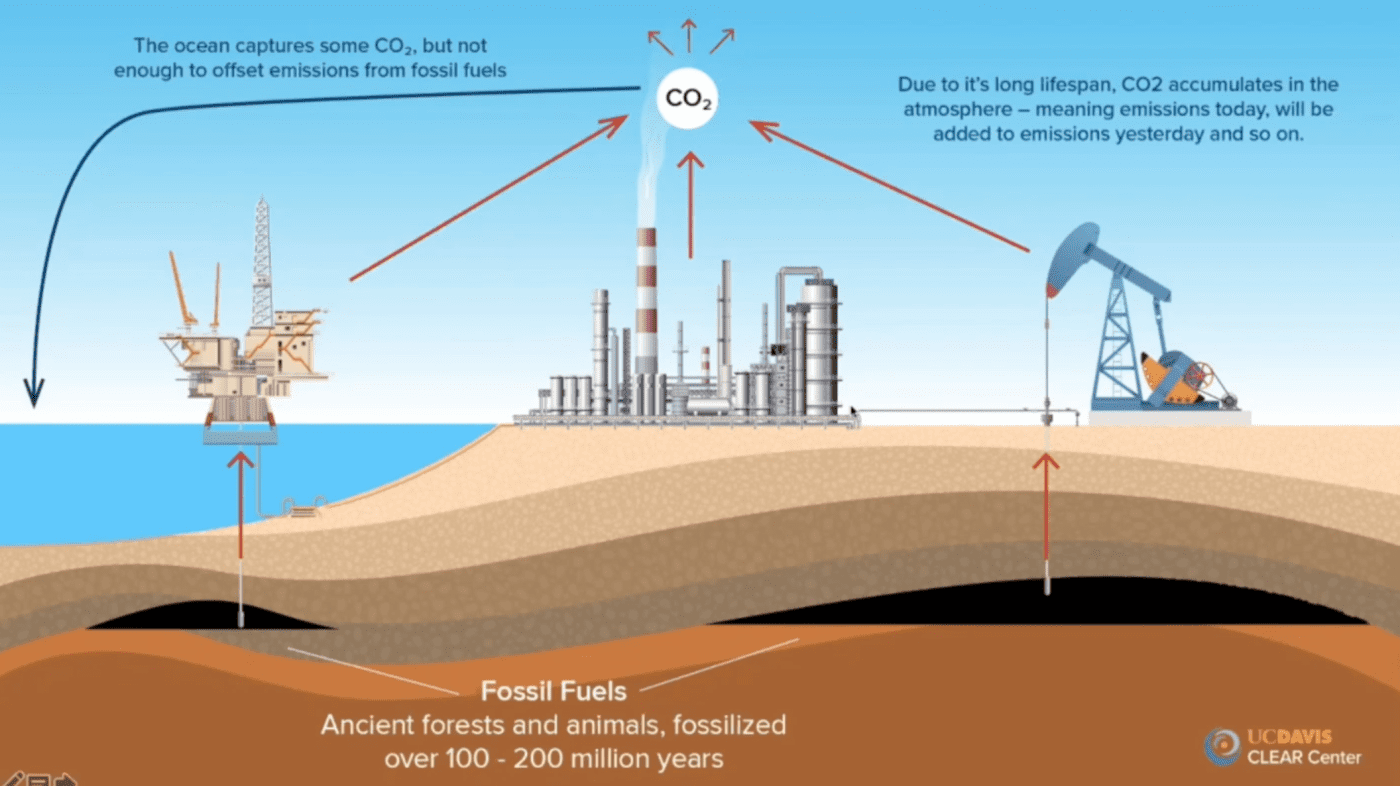

By contrast emissions from fossil fuel extractions were not part of a cycle, but “a one-way street”, because the amount of CO2 sent into the atmosphere in this process by far overpowered the potential sinks that could take up CO2, such as oceans, soils or plants.

“So here we have a one-way street. And this, ladies and gentlemen, is the main culprit of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere and the resulting warming.

“I have yet to see a climate scientist who would say that it’s the cows that are a primary culprit of warming. Most of them will agree that the primary culprit is the use of fossil fuels.”

“However, people critical of animal agriculture always point at cows, and cattle, and other livestock species. And they feel that this is a very powerful tool to ostracize animal agriculture as we know it.”

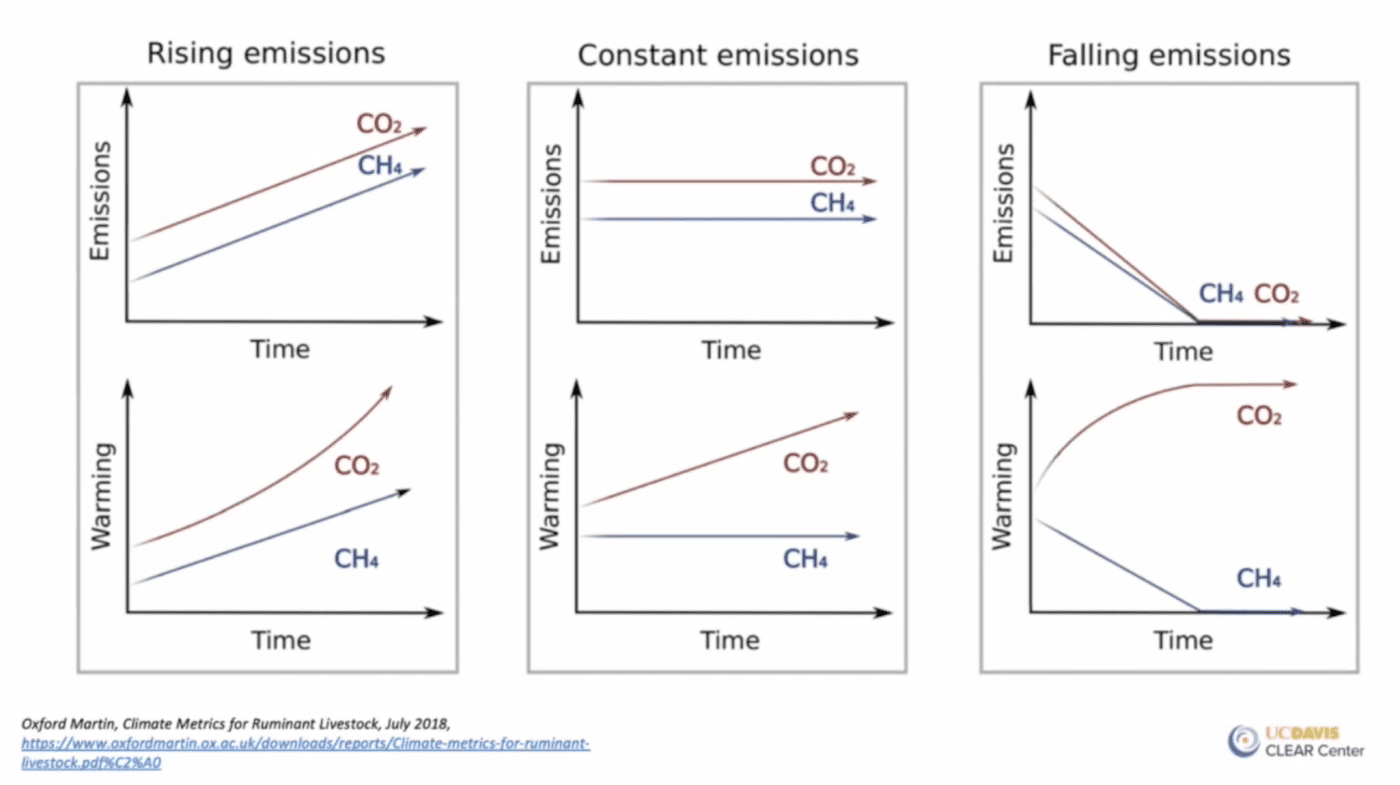

Not only were cattle not the primary culprit of global warming, they were also potentially part of the solution, as an explanation of stock gases versus flow gases demonstrated.

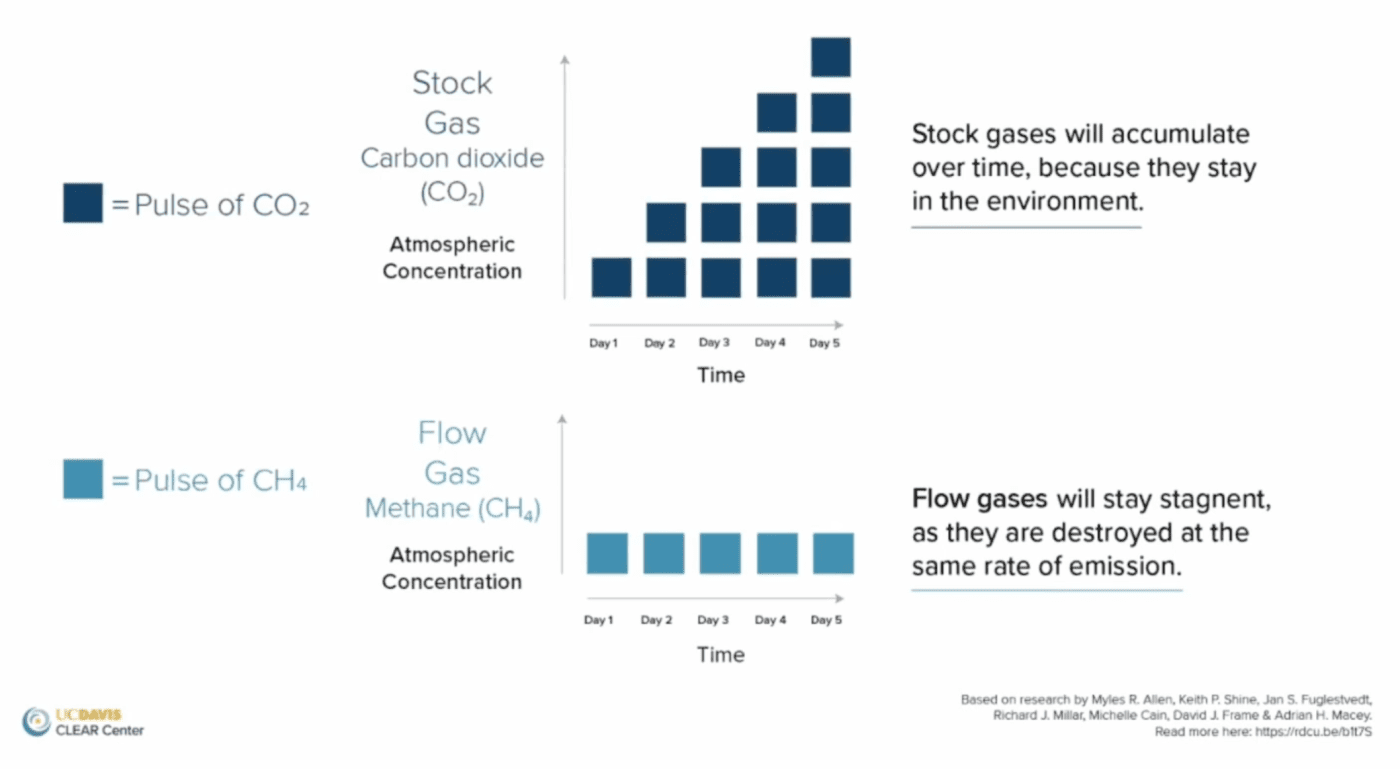

Long-lived climate pollutants such as Co2 were referred to as ‘stock’ gases because they last in the atmosphere for 1000 years. “Every time you put it into the atmosphere, you add to the existing stock of that gas,” he explained.

Methane (CH4) was a ‘flow’. Provided it was coming from a constant source, what was being put into the atmosphere was also being taken out.

“The only time that you really add new additional methane to the atmosphere with the livestock herd is throughout the first 10 years of its existence or if you increase your herd sizes.

“Only then do you actually add new additional methane and thus new additional warming.

“So please remember there are big differences between long-lived stock gases such as CO2 or nitrous oxide versus short-lived flow gases such as methane.”

He invited the audience to imagine a scenario where methane emissions from cattle were decreased by 35 percent.

If this could be achieved, it would have the effect of taking carbon out of the atmosphere and create a net cooling effect.

“If we find ways to reduce methane, then we counteract other sectors of societies that do contribute – and significantly so – to global warming, such as flying, driving, running air conditioners, and so on.

“So if we were to reduce methane, we could induce global cooling. And I think that our livestock sector has the potential to do it. And we are already seeing examples where that happens.”

He offered several examples of how the agricultural sector has already had success in reducing methane.

A few years ago the California legislature wrote a law called SB 1383 mandating a 40 percent reduction of methane to be achieved by the year 2030.

California’s farms and ranches have reduced greenhouse gases by 25pc since the laws were enacted.

This was achieved by using “a carrot rather than cane approach”, by rewarding farmers and ranchers who wanted to reduce emissions by giving them financial incentives to invest in anaerobic digesters or alternative manure management practices.

“I know if we can do it here, it can be done in other parts of the country and in other parts of the world.

“And if we indeed achieve such reductions of greenhouse gas, particularly of short-lived greenhouse gases such as methane, then that means that our livestock sector will be on a path for climate neutrality– on a path to climate neutrality. And that, to me, is a lifetime objective.”

Agriculture needs to work harder to tell its story

Dr Mitloehner said it was important the industry work harder to ensure the public understands the science around cattle production and greenhouse gas emissions.

“I feel that it is actually critical to get what we find in our research environment translated and communicated with the public sector.

“Because only if what we find makes its way to the light of the day, only then it matters”

It was also important that the public discussion used accurate and not misleading numbers around livestock emissions.

It is often stated that livestock emissions represent 14 percent to even as high as 50 percent of total emissions, but Dr Mitloehner said this did not reflect actual livestock emissions in developed countries such as the US were the number was closer to just 3 percent of all US emissions.