Could it be that a lot of cattle producers world-wide are being unfairly blamed for progressing climate change because of the methane released by their cattle? Going one step further, in this contributed article Alan Lauder, long-time grazier and author of the book Carbon Grazing – The Missing Link, suggests that the methane emissions of the Australian sheep and cattle industry are not changing the climate, because they have been stable since the 1970’s.

Cows up to speed on climate change

WE have to ask the question, is the current way of comparing methane and carbon dioxide, using the Global Warming Potential (GWP) approach, the best way to assess the outcome of the methane produced by ruminant animals like sheep and cattle?

I raise the point, keeping in mind that the debate is about “climate change”. We keep hearing the comment that we have to limit “change” to two degrees.

I am not suggesting that the science the IPCC and the world is relying on is wrong, but maybe it is worth having another look at how we are interpreting it in the area of ruminant animals.

The scientific evidence to support what follows in this weeks’ column, resides in the peer reviewed paper, “Offsetting methane emissions – An alternative to emission equivalence metrics”, which was published in the “International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control” – www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1750583612003064 (click on “Download PDF” after the link opens, then click on “Article”).

The thrust of the published paper is that we should be comparing “ongoing methane emissions (or reductions)” to “one-off emissions (or reductions) of carbon dioxide”. This weeks’ column will focus on the outcome of “ongoing stable methane emissions” from ruminants. The GWP approach focuses on one-off emissions and compares a one-off emission of methane to a one-off emission of carbon dioxide.

Ongoing stable methane emissions from cattle reach equilibrium

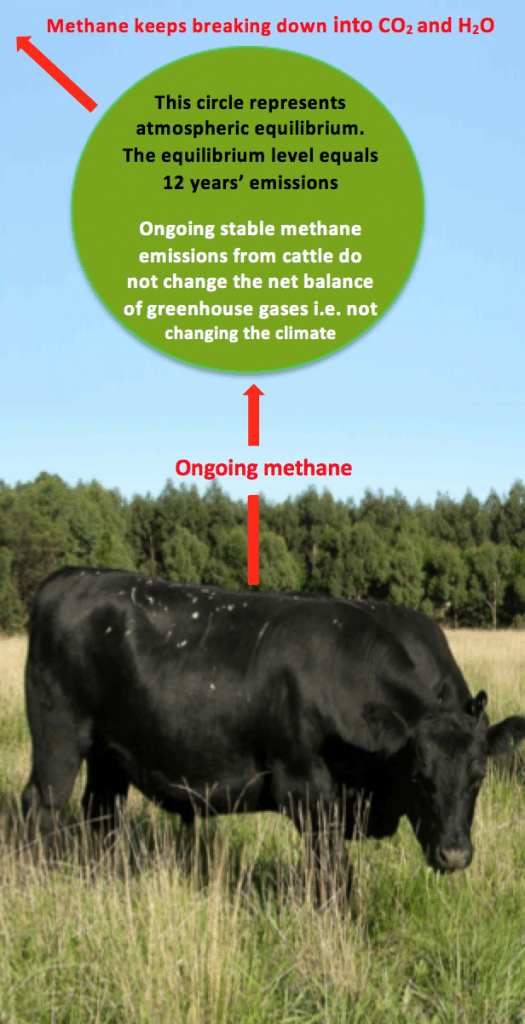

The best way to understand the diagram of the cow below is to visualise methane constantly being released by the cow and accumulating above it (in the green circle).

While the cow is releasing methane, past emissions will be breaking down in the atmosphere at the same rate. Methane lasts 12 years in the atmosphere (some suggest shorter), before being broken down into CO2 and H2O. It is broken down by a chemical reaction with hydroxyl radicals (OH) that keep forming in the atmosphere.

Assuming the methane released by the cow each year is the same, then the methane residing in the atmosphere (green circle) will be in equilibrium, with the additions and subtractions. It is true that cow size and pasture quality determines the amount of methane released, however, the fact the cow changes size and eats a different diet over time is a variable which averages out over time.

Further explanation of wording in diagram above:

The green circle could represent a paddock, a property or a country.

The equilibrium continues with the next cow put in the paddock and, all that follow.

This exercise only refers to agricultural emissions. Fossil methane (CH4) emissions are putting “New” CO2 into the atmosphere when the CH4 breaks down.

In the atmosphere, methane breaks down after 12 years into CO2 and H2O. Equilibrium is reached because CH4 is a short term gas that is chemically reactive.

Provided the emissions have been stable for a few decades, stable methane emissions do not change the net balance of greenhouse gases, i.e. don’t change radiative forcing.

With the reference to not changing the climate, the stability period has to be some decades more because, with all greenhouse gases, CO2 included, there is “committed warming”, which means some of the effect of past emissions is still to come because of the thermal inertia of the earth’s oceans.

Methane emissions from sheep and cattle in Australia peaked in the 1970’s, so are not contributing to climate change because the required period for stability and committed warming is covered.

Given CO2 accumulates, while methane does not, if methane from sheep and cattle are capped at today’s rate, this is the same as cutting CO2 emissions to zero.

In the diagram above, think of the equilibrium amount of methane, as a permanent balloon of methane that follows the cow around every day. When the cow is sent to the meat works and replaced by another cow, the balloon follows the next cow that is put in the paddock. In fact, all the cows that follow for the next 500 years.

The cow and its replacements, will be producing methane permanently, however, at the end of the life cycle of the methane, what is produced in the first year of the new cycle, will only be replacing the first year in the previous cycle, which will now be gone. Methane is not an accumulating gas like carbon dioxide is.

How the atmosphere functions

I am a very basic person, I like to get back to basics and go from there. So let’s look at the climate change debate from the atmosphere’s perspective, and how it functions.

The atmosphere does not understand the difference between all the different greenhouse gases, nor the comparative figures we put on them with the GWP approach. It only understands the total “radiative forcing” of all the gases combined. A bit like we are only interested in the flood height, not where all the water came from.

The warming effect of each greenhouse gas is known and is referred to as “radiative forcing” and is measured as watts per cubic metre of gas. Stabilising the climate relies on stabilising the total radiative forcing of all the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The purpose of the cow diagram was to show that ongoing stable methane emissions from ruminants, do not change the total radiative forcing.

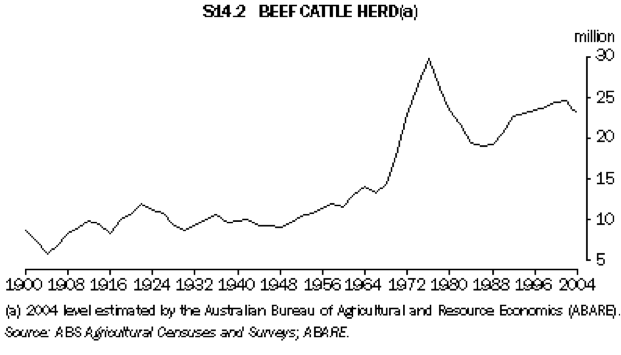

Australian methane emissions

If you talk to the atmosphere, it sees sheep and cattle in Australia as the mouse in the room in terms of the changes it is witnessing.

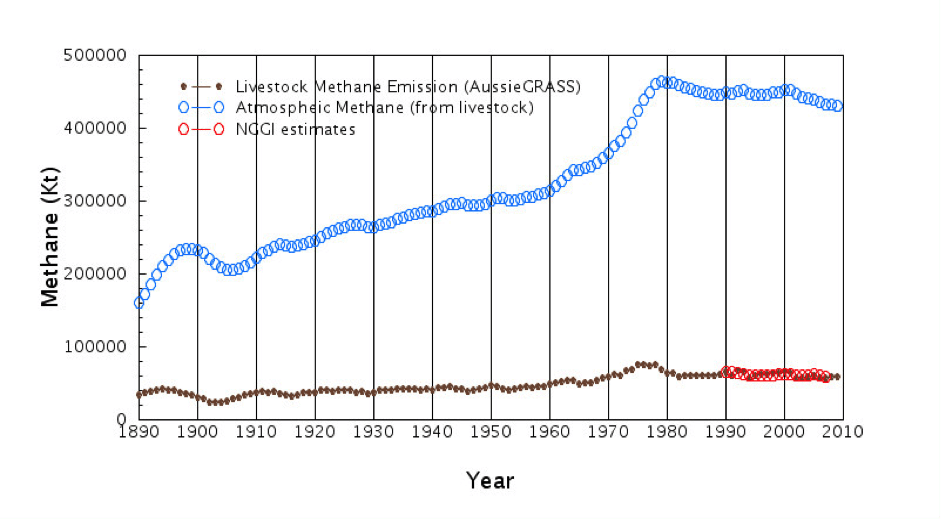

This is because the combined methane emissions of sheep and cattle in Australia peaked in 1970 and have basically remained stable since, with just a slight decline. This is a little known fact. It is interesting to note that the 1970’s was the last time the herd was at 30 million head. So while it is true that methane from Australian ruminants have always influenced the day to day climate, in recent times, their methane has not been a cause of the ongoing change in the net balance of greenhouse gases, as the diagram below shows.

The bottom line on the graph is the amount of methane released each year by livestock.

The top line on the graph is the net mass of methane attributed to livestock. The net mass is emissions less what has broken down. It is often referred to as the atmospheric burden.

The amount of methane in the atmosphere is still increasing, however this is not due to Australian ruminants.

The methodology behind the GWP approach

The Global Warming Potential (GWP) approach has been widely adopted as the metric for comparing the climate impact of different greenhouse gases.

For those wanting to know exactly how the GWP methodology came into being, read the paper, “The global warming potential – the need for an interdisciplinary retrial” by Keith P Shine.

The GWP approach was designed for decision makers in government and considers three time horizons, 20/100/500 years.

As Keith Shine explains in his paper, decision makers were presented with modelling showing comparisons over 20 years, 100 years or 500 years, they put their finger on the middle time horizon and ran with it. That is why we have the 100 year rule.

How I came to my current position

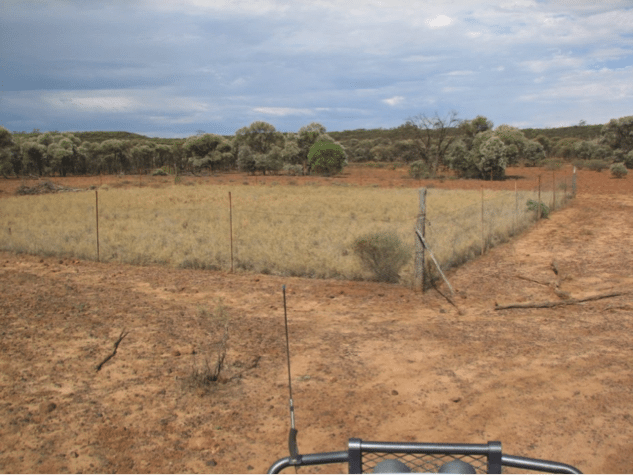

When I went into Idalia National Park in Nov 2009, a year that was very wet in the first half, the photo below is what I saw. There were no sheep or cattle in the park, just kangaroos. It was obvious that the kangaroos had completely shut down the carbon flows in the area between the trees, i.e. carbon that should have been in the paddock was still in the atmosphere.

An enclosure inside Idalia National Park, west of Blackall. Photo taken 14/11/2009

At the time, it was being suggested by some that sheep and cattle should be replaced with kangaroos because kangaroos emit virtually no methane.

It was a perfect example of having a single issue debate and not looking at the big picture (taking a systems approach).

I then decided to compare the carbon footprint of kangaroos versus sheep and cattle. If kangaroos reduce carbon flows, then their methane advantage is immediately being eroded. Also, a kangaroo researcher at the University of Sydney had told me that kangaroos are even more selective than sheep in what they choose to eat. This means that when they are present, they are reducing the digestibility of the diet available to cattle, which means the cattle will then produce more methane per kg of production.

As somebody who knew absolutely nothing about how the atmosphere functioned, I started reading and really struggled, as it was so complicated. However, having no formal training in the area, meant I was reading with no preconceived ideas.

After I progressed past the stage of total confusion, something did not add up with how the science was being applied in regard to ruminants. If my memory serves me right, it was the three different figures placed on methane that really started me thinking. One thing lead to another and then a group of well respected scientists joined me in thinking outside the square. Hence the paper referred to at the start.

The peer reviewed paper

In the paper “Offsetting methane emissions – An alternative to emission equivalence metrics”, the science is very complicated but the logic is not. The reference to “equivalence metrics” is a reference to the GWP approach.

The paper is part of an emerging body of work on how to do better than the 1990 IPCC approach. As well as our paper, Smith has written one and later Myles Allen has also written a paper. The paper has been cited by another paper.

The way the GWP approach works, is that ONE OFF emissions of methane are compared with ONE OFF emissions of carbon dioxide. Also, the GWP approach comes up with different figures when comparing methane and carbon dioxide, depending on the time frame of the comparison. If we are looking 20 years forward, then they say methane is 72 times worse than carbon dioxide, 21-23 times worse if the time frame is 100 years, 7.6 times worse if the time frame is 500 years.

However, our paper makes a strong case for comparing ONGOING emissions of methane with ONE OFF emissions of carbon dioxide. This approach gives the same comparison between methane and carbon dioxide, regardless of the time horizon chosen.

Experts in the field initially struggle with this approach much more than lay people, because their mindset is fixed on the GWP approach and how it compares methane and carbon dioxide.

Applying the science of the paper in the paddock

After suggesting that methane and carbon dioxide should be compared differently, the paper then looks at how much carbon needs to be sequestered in the paddock, to remove the effect of the ongoing stable methane.

The paper proposes that a one-off sequestration of 1t of carbon would offset an ongoing methane emission in the range of 0.90 – 1.05 kg CH4 per year. Provided we keep the carbon from the CO2 in the landscape, then the one off sequestration accounts for the ongoing methane for centuries.

The paper came up with building up the sink over forty years, a bit like paying off an interest-free loan at 2.5% of the balance each year.

Applying the equation published in the paper is like leaving the cows in the paddock as if they were not emitting methane.

Putting it another way, the green circle above the cow in the diagram, is the atmospheric burden produced by the ongoing methane and, this is what has to be offset by bringing down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it’s carbon in the paddock.

Because of the way the atmosphere functions over time, the paper had to apply the 0.3 factor (about to be discussed) to calculate the figure for carbon. The 0.3 factor increases the figure for carbon because sink efficiency reduces over time.

Committed warming, which was mentioned in the column beside the cow diagram, did not have to be considered in the offsetting calculations, because it applies to both CO2 and CH4.

In a sense, the paper documents how producers can be part of the solution. The equation in the paper is reversing climate change. Even offsetting 5% of ongoing stable methane is reversing climate change.

Realistically, nobody expects cattle producers to be applying the paper’s equation and reversing climate change, when society has chosen to let climate change continue with the ongoing release of carbon dioxide.

However, there are plenty of cattle producers who are good managers of carbon flows, who without even realising it, are applying the paper’s equation. This is because better management of carbon flows increases paddock carbon, especially short term carbon. I deliberately mentioned short term carbon, because the atmosphere doesn’t differentiate between short term carbon and long term carbon. It just knows that the carbon atom is not in the atmosphere.

The 0.3 factor

Feel welcome to skip this section and the next one. They are a bit heavy going and are included more to answer the questions technical people would be asking.

When the paper calculated how much carbon has to be removed from the atmosphere, and stored in the paddock, to offset the ongoing stable methane emissions, the oceans had to be considered. This is because carbon dioxide moves between the oceans and the atmosphere, as part of rebalancing.

For fossil carbon emissions, this re-balancing of carbon by the oceans works for you, and takes some of the carbon out of the system. For sequestering carbon, the re-balancing of carbon by the oceans works against you.

Atmospheric scientist, Pep Canadell explains that in the short term, in times of growing CO2 emissions, a proportion of 0.4 remains in the atmosphere. This is called the airborne fraction. When one looks at the longer term, this fraction drops to a proportion of 0.3 (the 0.3 factor that we use in the paper). Put simply, if you are talking long term, for every tonne of carbon you remove from the atmosphere, the end result will be a reduction of 0.3 of a tonne in the atmosphere.

The 0.3 is called “the airborne fraction of cumulative emissions”.

The long-term nature of CO2 is what justifies balancing it against the long-term equilibrium CH4 level, in which case, you have to use the actual long-term number for CO2.

Putting all this into a layman’s perspective, you have to sequester three times more than simple logic suggests. The reduction in “sink efficiency” is because of the rebalancing of carbon by the oceans is undermining your efforts on land.

The abstract of the paper

“It is widely recognised that defining trade-offs between greenhouse gas emissions using “emission equilivalence” based on global warming potentials (GWPs) referenced to carbon dioxide produces anomalous results when applied to methane. The short atmospheric lifetime of methane, compared to the timescales of CO2 uptake, leads to the greenhouse warming depending strongly on the temporal pattern of emission substitution.

We argue that a more appropriate way to consider the relationship between the warming effects of methane and carbon dioxide is to define a “mixed metric” that compares ongoing methane emissions (or reductions) to one-off emissions (or reductions) of carbon dioxide”. Quantifying this approach, we propose that a one-off sequestration of 1t of carbon would offset an ongoing methane emission in the range of 0.90 – 1.05 kg CH4 per year.

Our analysis is consistent with other approaches to addressing the criticisms of GWP-based emission equivalence, but provides a simpler and more robust approach while still achieving close equivalence of climate mitigation outcomes ranging over decadal to multi-century timescales”.

Conclusion

If you believe in human induced climate change, then it is the long term gas carbon dioxide which will paint us into the corner, not stable methane from ruminants (sheep and cattle).

“Stabilising the climate means cutting all future carbon dioxide emissions and stabilising ongoing methane emissions from ruminant animals. This statement does not apply to fossil methane which is different to ruminant methane as it keeps adding a new carbon atom to the atmosphere.

Sheep and cattle produce less methane per kg of production when carbon flows are managed better. This is because the digestibility of their diet is better. Also, with better management of carbon flows, the extra carbon (including short term carbon) residing in the paddock is offsetting some of the equilibrium methane.