BOTTLE teats have been found to be a major cause of calf loss in a recent study of a northern beef herd.

Principal Livestock Research Officer from the Northern Territory Department of Industry, Tourism and Trade, Tim Schatz, was the leader of the recently concluded CalfWatch project.

“Using a system of birthing sensors and GPS collars, we studied 200 cows soon after calving, over two years,” Mr Schatz said.

“The cows were run in a typical north Australian breeder paddock, 2215 ha in size, uncleared with mostly native pastures. Calf loss rates were 17 percent in both 2019 and 2020. We saw a number of causes of calf loss including early abortion, dystocia, infection of the umbilical cord and pneumonia, but these were only one or two cases each.

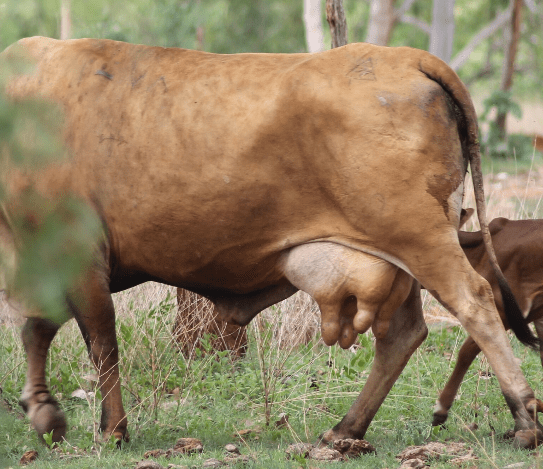

“The most common cause of calf loss we identified was cows with bottle teats immediately after calving.”

During the trial, 5-6pc of all pregnancies resulted in calf deaths attributed to bottle teats.

“We were surprised by what we saw,” Mr Schatz said.

“Many of the cows that had bottle teats at calving, had normal appearing udders only a few weeks later. If this is typical of northern herds, it is likely these cows are going through the yards later in the year without being culled.

“If this is the case, they will only continue to lose calves in the following seasons. So, producers could consider culling all cows that don’t raise a calf to weaning as a way of removing these cows from the herd. We wouldn’t have known bottle teats were the cause of the issue if we hadn’t been using the CalfWatch system which allowed us to see the cows at calving.”

The CalfWatch system

One of the alert ‘gateways’ used in the CalfWatch project.

Mr Schatz and his team, worked closely with researchers from the University of Florida to modify existing system using birth sensors. The modifications increased the range and usability of the birth sensors in locations with limited mobile phone coverage.

“The intra-vaginal birthing sensors and GPS tracking collars were applied in August, before expected calving in October to January. As the calf makes its way through the birth canal, the sensor is expelled. As it registers a rapid temperature change, the sensor emits a UHF signal,” he said.

“This is received by antennas in a low-power wide-area network (LPWAN), which is then transferred by a gateway, via the internet, to servers owned by the sensor manufacturer.

“The alert is transmitted in real time to a supporting website, which then sends an email to our team. Upon receiving the notification, our team locates the cow using it’s GPS collar. From a distance, we recorded the calf’s health, date of birth and maternal observations.”

When asked about the significance of the findings to calf loss research, Mr Schatz said: “Having the ability to find the calf within an hour or so after birth has been a considerable development. Historically, determining the cause of calf loss in extensive beef operations has been challenging.

“Large paddocks, trees, tussocky native pastures and predators, such as wild dogs and pigs, have all made locating calf carcasses in time for a post mortem, quite difficult. In these circumstances, we could only identify calf losses after a pregnancy tested in-calf cow returns dry, some months later. Using the CalfWatch system, if we found the calf dead, we were able to conduct a post mortem.”

Successes and developments

The CalfWatch project achieved the original aims:

- increasing understanding of the causes of calf loss in extensive herds

- developing a system to remotely monitor calving.

While helpful results were obtained, there were some technological problems along the way. During the first year, some of the GPS collars malfunctioned, making locating recently calved cows difficult to find. The GPS collars worked significantly better after adjustments were made the following year.

During the second season, the same birth sensors from the previous year were used, but nearly 50pc of the birth sensors failed.

If the research was to be conducted again, the improved GPS collar design and only new birth sensors, would be used.

However, efforts are underway to develop calving alert collars that send alerts and GPS data in real time.

“A calving alert collar that uses accelerometer data to identify calving, will enable birth date and location to be identified remotely without the need for birth sensors,” Mr Schatz said.

“Calving alert collars will be a better solution as birth sensors are invasive, and can be expensive and complicated to use. In contrast, calving alert collars that provide alerts and location data in real time, are much easier to use and may also be used by industry where it is important to identify calving dates.”

Mr Schatz said that some situations where birth sensors might be used by industry are to identify calving in high value animals, to enable collection of birth date data to enable more animals to be included in Breedplan, and also to identify the causes of calf loss where it has been identified as a problem.

CalfWatch is co-funded by Meat & Livestock Australia and the Northern Territory Government.

Source: FutureBeef