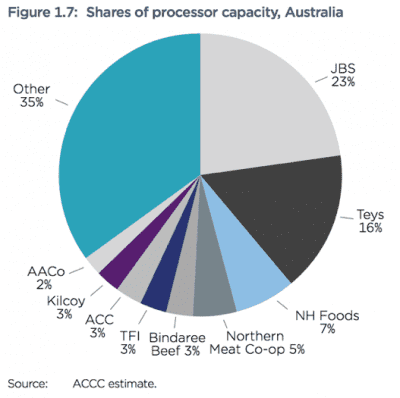

The ACCC study said the Australian beef processing sector is dominated by two large firms, JBS Australia and Teys Australia, which operate multiple processing facilities across the eastern states; several medium scale operators, including NH Foods, Northern Cooperative Meat Company, Thomas Foods International, Bindaree Beef and Australian Country Choice; and a range of smaller processors. The ACCC estimated that Australia’s five largest processors accounted for around 54 per cent of total slaughter capacity. Click on chart to enlarge.

TWO years ago the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission agricultural unit conducted a six month investigation into competition issues in the Australian cattle and beef market.

The ACCC noted that producers had raised concerns that consolidation in the processing sector had reduced competition in cattle markets, resulting in lower prices for producers.

In response to those concerns the ACCC made an assessment of existing levels of competition among processors.

In response to those concerns the ACCC made an assessment of existing levels of competition among processors.

Its final report noted there had been a significant decline in the number of beef processing plants and firms in Australia over the past 35 years.

Data from the Australian Meat Industry Council (AMIC) showed that around 90 abattoirs closed between 1980 and 2003.

Despite that large reduction in the number of facilities, overall processing capacity in fact increased, the ACCC report said, as processors sought to improve efficiency through scale.

The closest the ACCC came to making a definitive assessment about whether existing levels of processor competition are adequate was the following statement:

“Close competition for the acquisition of prime cattle typically takes place within regional areas of approximately 400 km from a point of sale and most producers of prime cattle in Australia have access to various buyers within the regional market in which they sell their cattle.”

However, the ACCC also noted that exceptions included North Queensland and Tasmania, and it warned that if further consolidation in the processing sector was to occur through mergers, acquisitions or other conduct, such deveopments “would substantially lessen competition”.

How does abattoir capacity in Australia compare to actual supply?

Another study released in April 2018 attempted to provide an estimate of cattle supply versus processing capacity in Queensland.

The study, conducted by Victorian engineering consultancy firm MeatEng and commissioned by the Queensland Government, suggested the supply of slaughter cattle available to Queensland processors in 2017-18 was in the order of 3,450,000 head, including dairy cattle.

Using historical monthly slaughter throughput of all Queensland beef abattoirs from January 2000 to July 2017, the reported indicated that capacity typically exceeds supply in Queensland, with estimated capacity of 390,000 cattle per month in the State (operating on a five day per week basis) having been exceeded by available supply only 7 times in the 211 months of data.

ACCC report highlights barriers to entry for new processing projects

The investigation also assessed the various barriers to entry new meat processing projects must overcome.

The report suggested a minimum scale of 400 head of cattle per day was the minimum efficient capacity a new abattoir would require – however it noted there was also scope for new entry on a smaller scale targeting niche markets (see below).

The ACCC found several “significant” barriers to entry into processing existed in most regions of Australia, including:

The requirement for economies of scale:

For the most part, large scale entry is required for cost competitiveness against incumbents, the ACCC said.

This need for large economy of scale increased the risk of entry, particularly if a correspondingly large share of the market had to be won from incumbents for the project to operate successfully.

“Studies suggest that the minimum efficient scale of a new abattoir is the capacity to process a minimum of 400 head of cattle per day.

“A new plant of this scale would cost between $33 million and $49 million.”

High capital and sunk costs:

While high capital costs were not necessarily a barrier to entry, the proportion of the capital and other costs which are sunk costs, and uncertainty about cash flows arising from fluctuations in market conditions also increased the risk of entry, the ACCC report said.

Uncertain and fluctuating cattle supply:

The ACCC report identified two main sources of risk that cattle supply would be insufficient to support the viability of new processing plants:

– Volatility in the supply of cattle due to seasonal and cyclical factors, and

– Potential responses of incumbent processors who may be able to use excess capacity to expand production and make it harder for entrants to acquire the minimum volume required for successful entry.

“Such strategic behaviour by incumbents could also reduce the profitability of entry by increasing the prices of cattle acquired and lowering prices received for beef,” the ACCC report noted.

The burden of high regulatory requirements and costs:

A broad range of regulations and associated costs apply to beef processing facilities, including an export inspection system, labour regulations, customer audits and food safety requirements.

Other regulatory costs include fuel excise charges and workplace health and safety provisions, as well as environmental management plans.

The ACCC found that the level of regulation and compliance imposed in the food processing sector has increased in recent years.

The process to obtain compulsory accreditation from AUS-MEAT to supply domestic and/or export markets was described as “a stringent and rigorous set of steps” which includes the accreditation application, inspections to assess compliance with National Accreditation Standards (NAS), development of a Quality Management System and AUS-MEAT training courses for staff, and ongoing regular compliance audits.

Barriers to entry also vary according to abattoir size

The ACCC study report included the observation that there appears to be greater scope for new entry on a smaller scale targeting niche markets.

Niche entry was unlikely to have the same imperative for large economies of scale, as the end beef product was differentiated and could therefore command higher prices.

“This would also likely require lower capital costs and is less likely to provoke retaliation by incumbents.”

The ACCC report identified three recent examples of abattoirs being either constructed or reopened:

– In 2014, AACo opened a new beef processing facility near Darwin with a capacity of up to 1000 head, and costing $91 million over two years to construct .

– In 2014 a mothballed plant at Young was reopened by Hilltop Meats at a cost of $10m.

– In September 2016 the Kimberley Meat Company abattoir opened near Broome with a capacity to process up to 300 head of cattle a day at a reported cost of over $40m.

The ACCC report (which was released back in March 2017) noted the AACo and Kimberley Meat Company were opened in areas where little or no processing capacity existed.

It said the capital costs of re-establishing the mothballed plant at Young were understood to be significantly lower than establishing an entirely new plant, which made re-entry viable despite existing capacity in the market.

The ACCC report concluded that the viability of entry would depend on a case by case analysis, and the presence of existing unused infrastructure or a lack of existing capacity would have a significant impact on this.

High barriers to entry can have the effect of limiting competition

The ACCC report also made the point that a processor’s ability to exercise market power depends on the extent to which it is constrained by the threat of new processing capacity entering the market, or the expansion by an existing competitor.

The ACCC said it considered that the threat of entry or expansion was effective only if it was likely to occur in a timely way, and was of sufficient scale and nature to affect the behaviour of incumbents.

“The timeliness of entry and expansion depends on the dynamics of a particular market, but the ACCC generally considers that entry will only be an effective constraint on the market power of incumbents if it could occur within 1–2 years.”

Link to report: https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/ACCC%20Cattle%20and%20beef%20market%20studyFinal%20report.pdf