LONG before texting, smart phones, faxes or even public pay-phone boxes existed, Australia’s meatworks livestock buyers used an elaborate system of code to relay important messages back to head office about their buying activity and prices paid.

With literally dozens of meat processing plants operating across eastern Australia in the post war years, every livestock sale across the country attracted a large gallery of company fat stock buyers, and large runs of bullocks and cull cows would be sold out of the paddock annually on handshake deals.

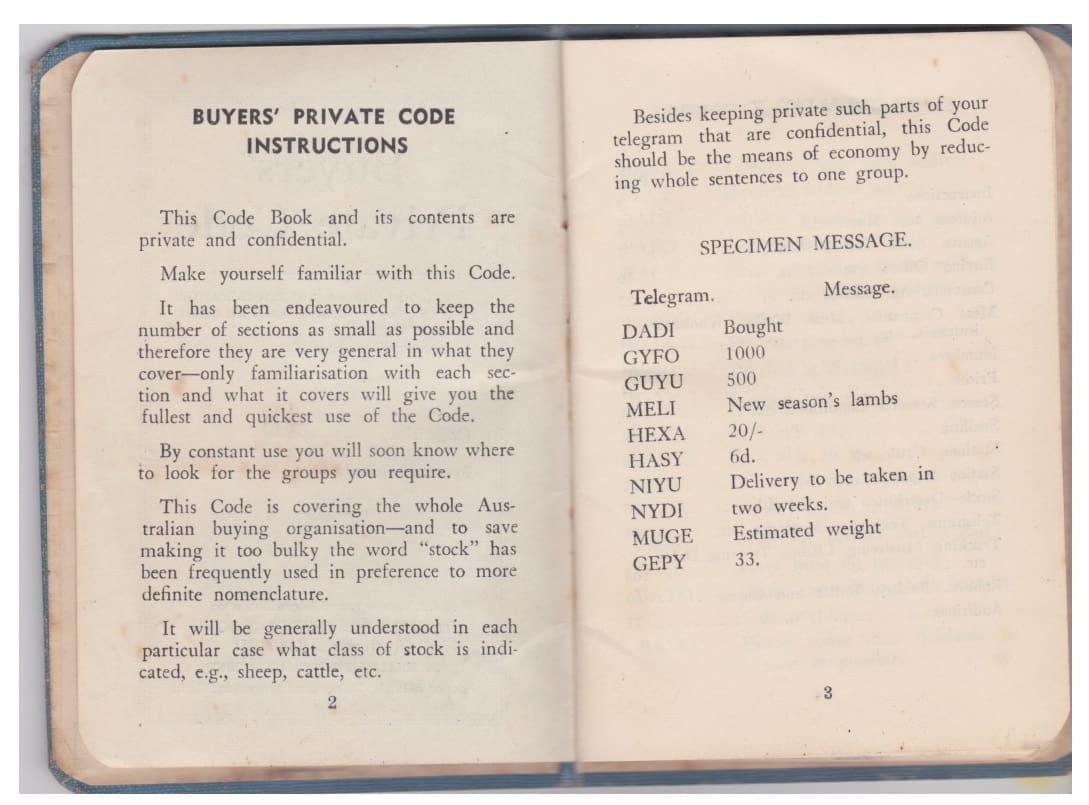

Meat companies had to find a way to transfer this information back to head office, without nosy competitors finding out what number of stock had been bought, and what price paid. In reverse, instructions at times had to be relayed back from head office to buyers about buying strategies, bidding limits, and where to go next.

Seventy years ago, telegrams were apparently the primary source of communication between buyers and head office. After each sale, each company’s buyer would race down to the nearest post office to send telegrams back to head office about what he had purchased, what was paid, and other commercially sensitive information.

The fear was that a loose-lipped telegram operator in a small country town could easily be bribed for information about a competitor, for a few shillings

Keeping all this secret was the challenge. The fear was that a loose-lipped telegram operator in a small country town could easily be bribed for information about a competitor, for a few shillings.

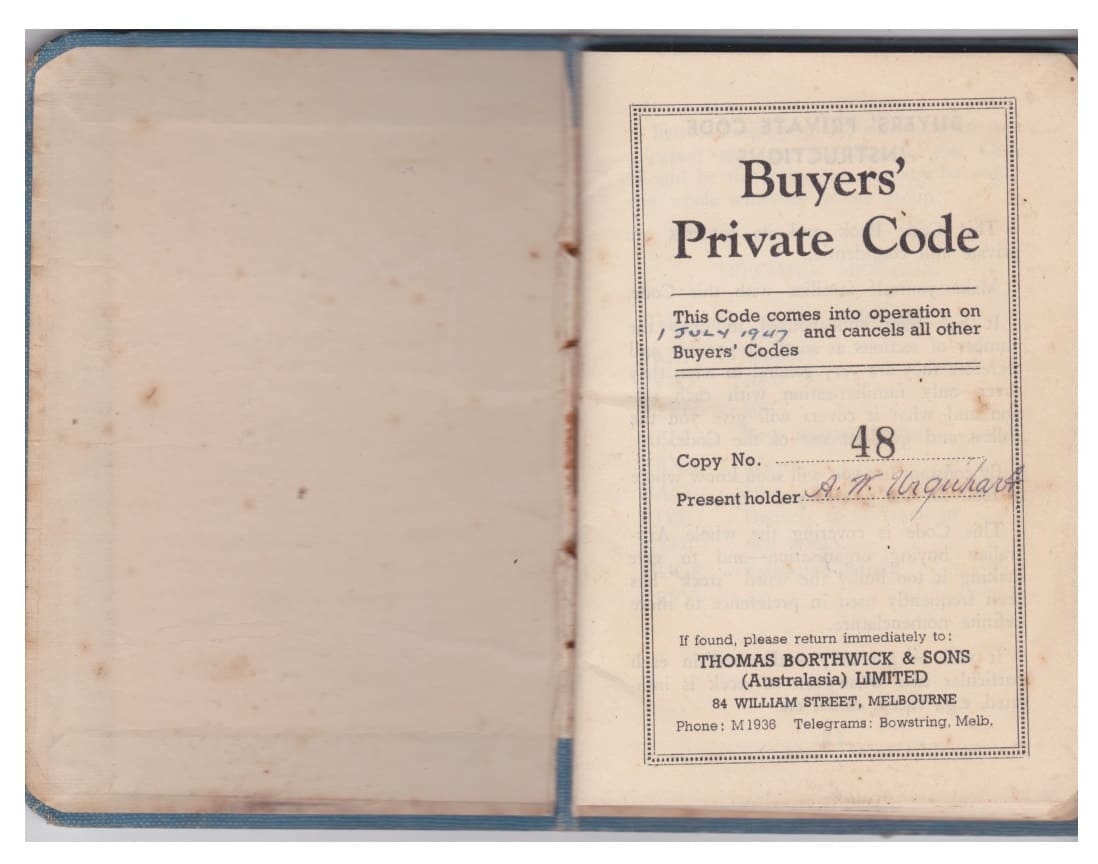

Former Thomas Borthwick & Sons meat sales executive John Urquhart recently sent Beef Central some images from a 1947 vintage Borthwicks Buyers’ Private Code book. The book – copy number 48 – was issued to his father, Alec Urquhart, who bought cattle, sheep, lambs, pigs and even rabbits for Borthwicks Portland abattoir for 37 years. He died in 1970.

In the post-war years, rabbits in fact played an important role in filling the protein gap caused by rationing in Australia, which extended into the early 1950s.

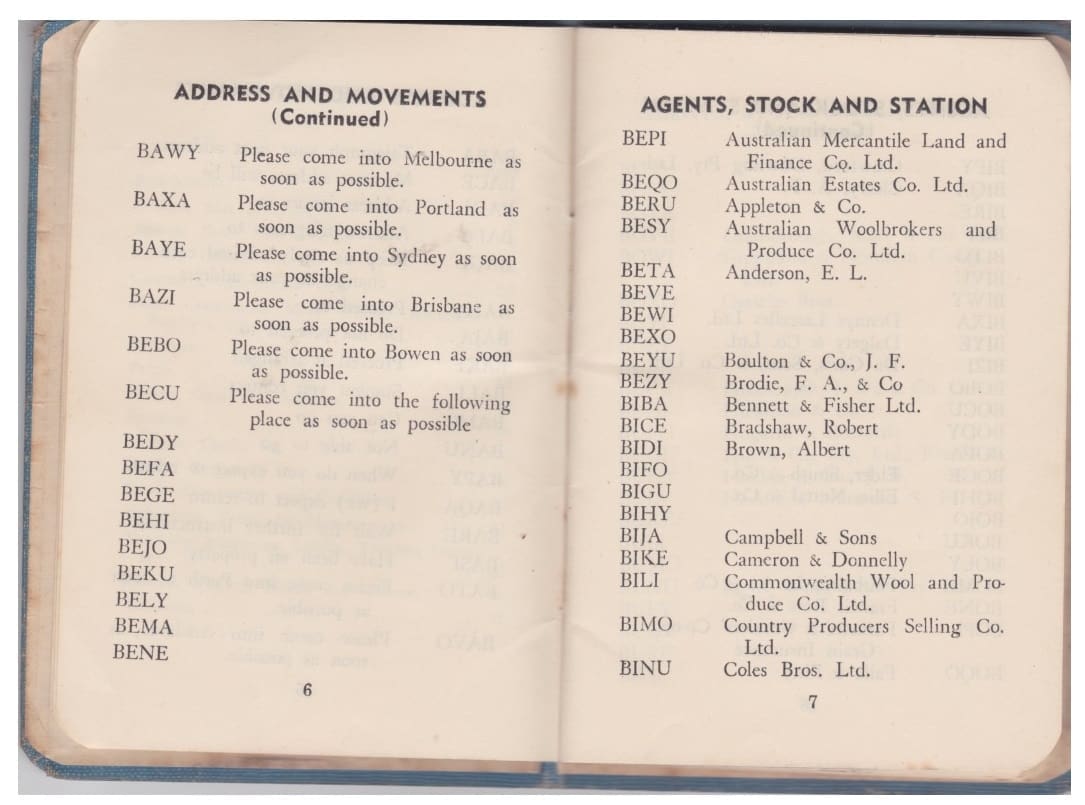

Borthwicks at the time ran plants at South Brooklyn, Portland, Moreton near Brisbane and Bowen in North Queensland.

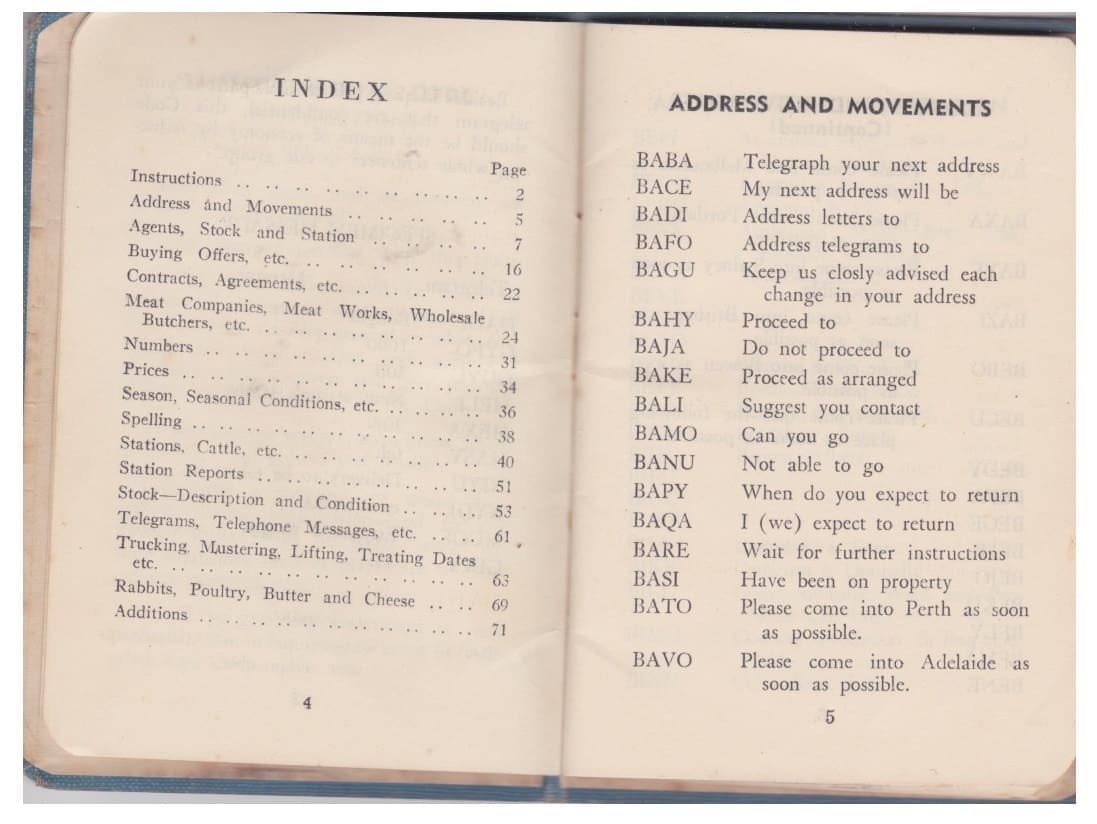

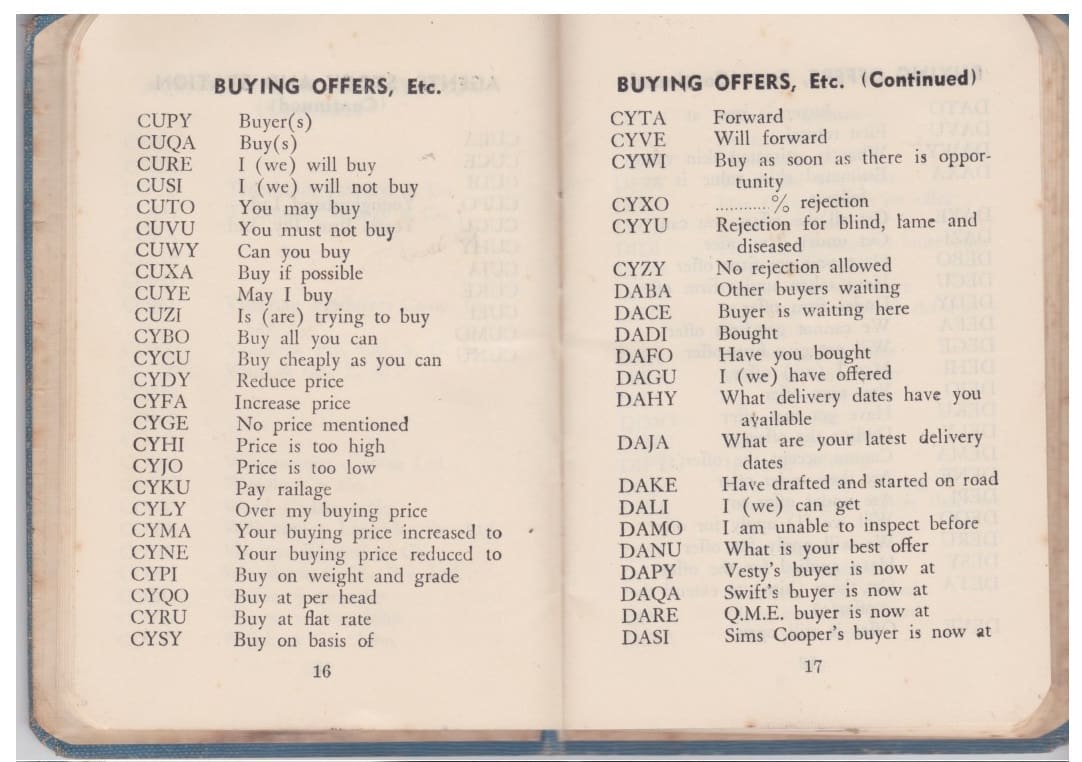

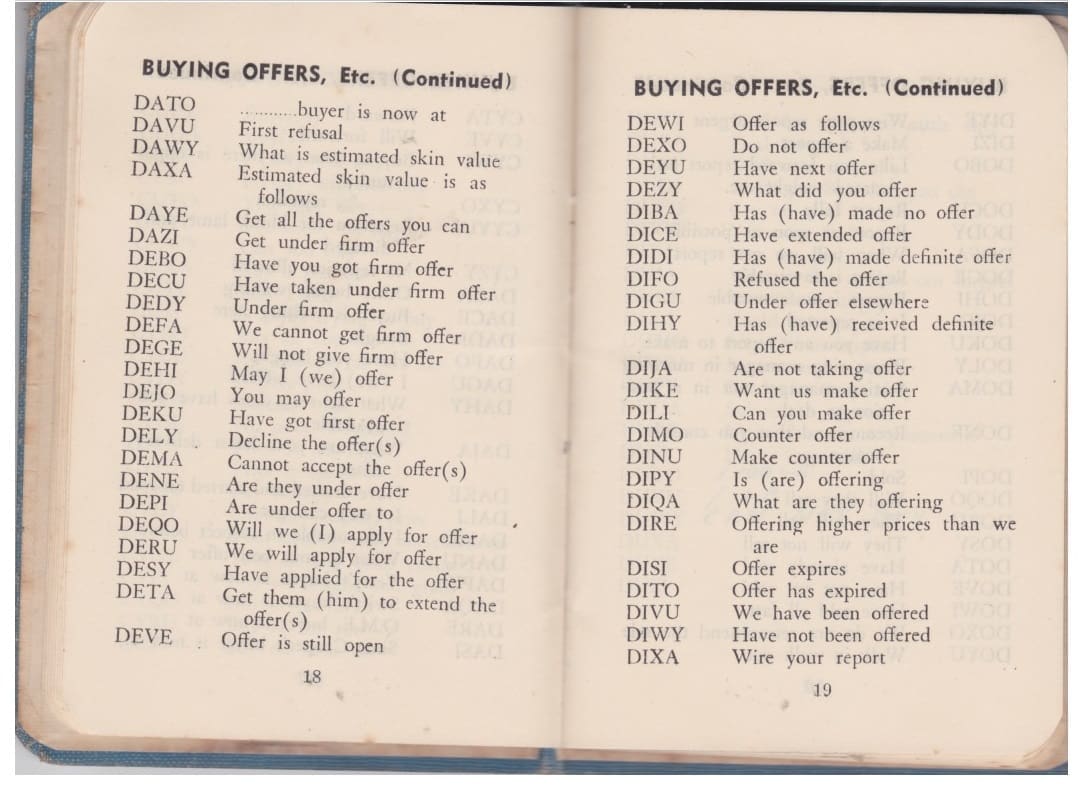

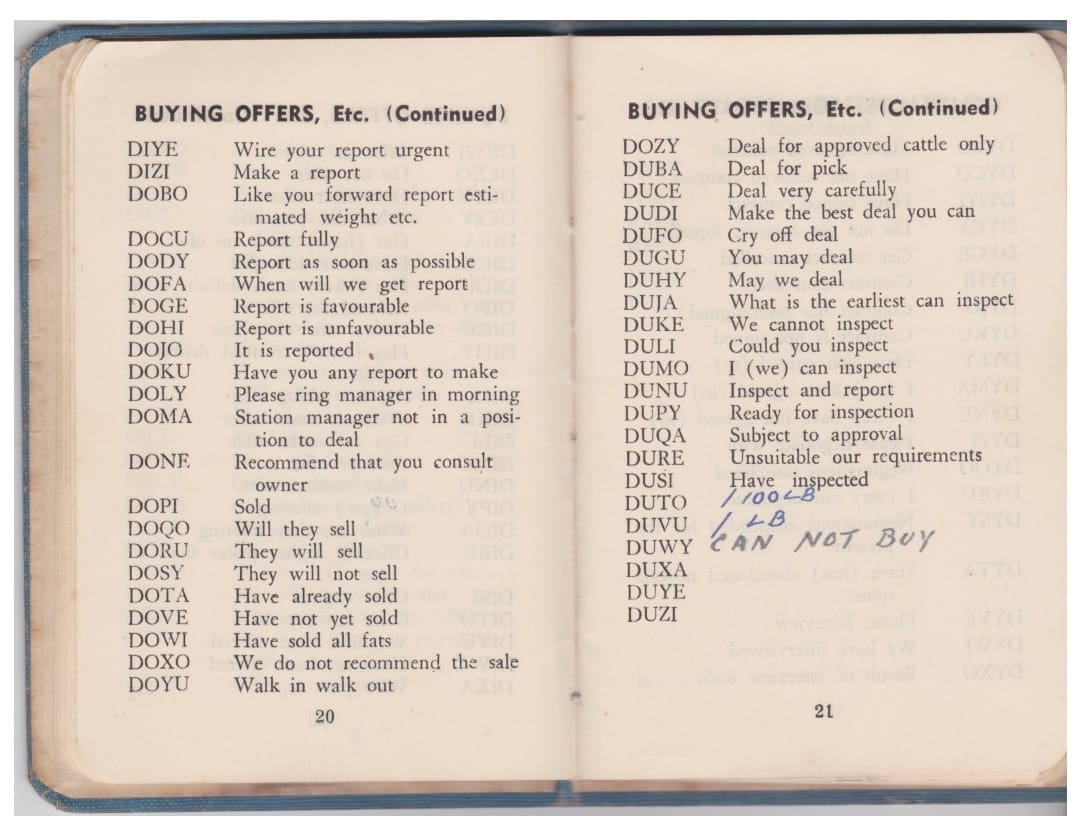

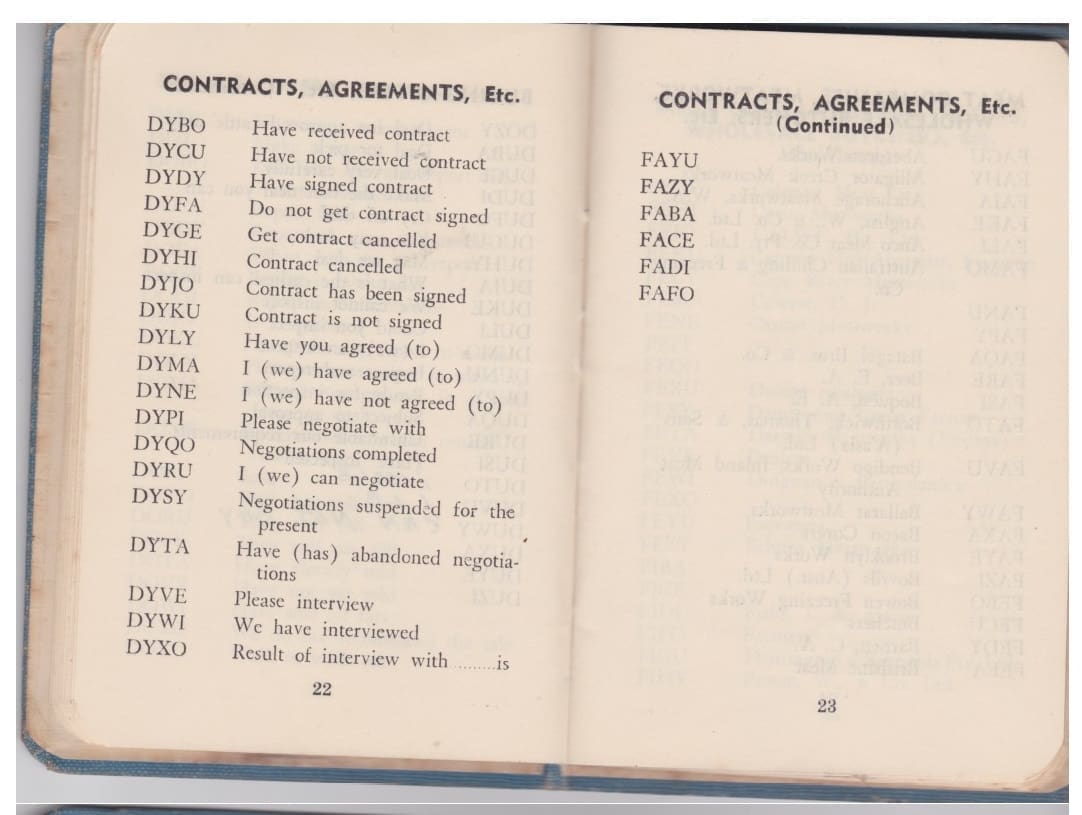

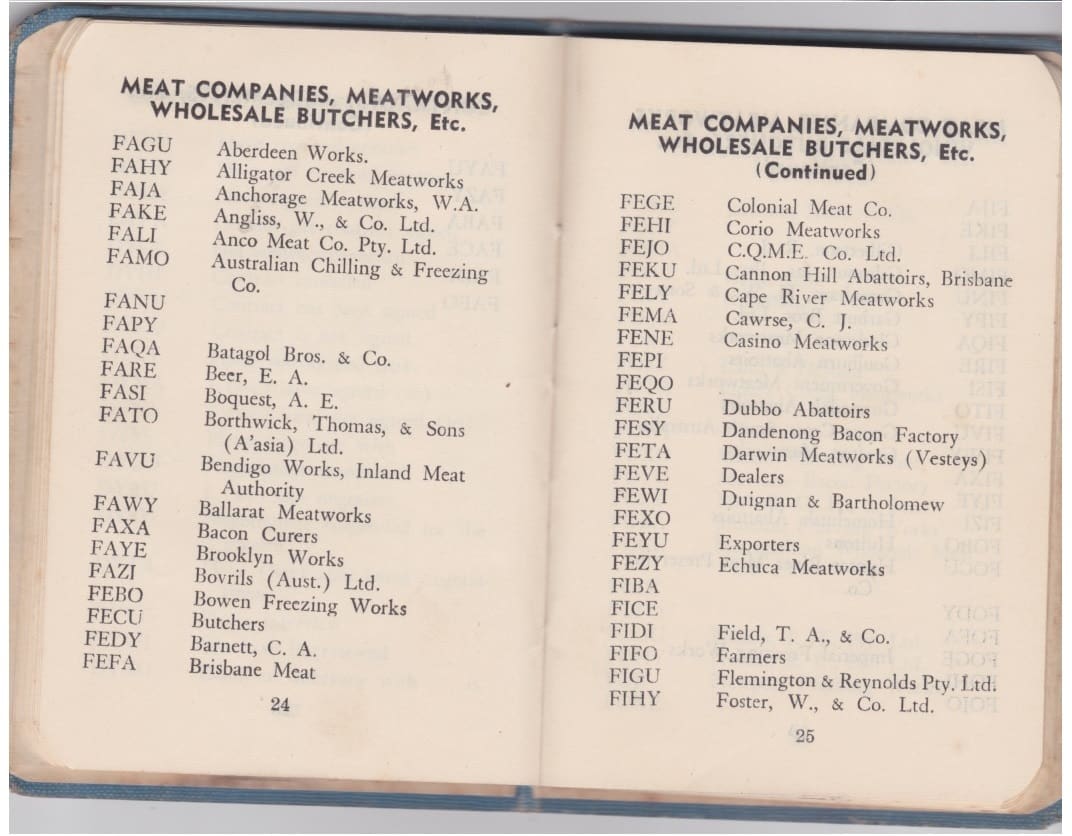

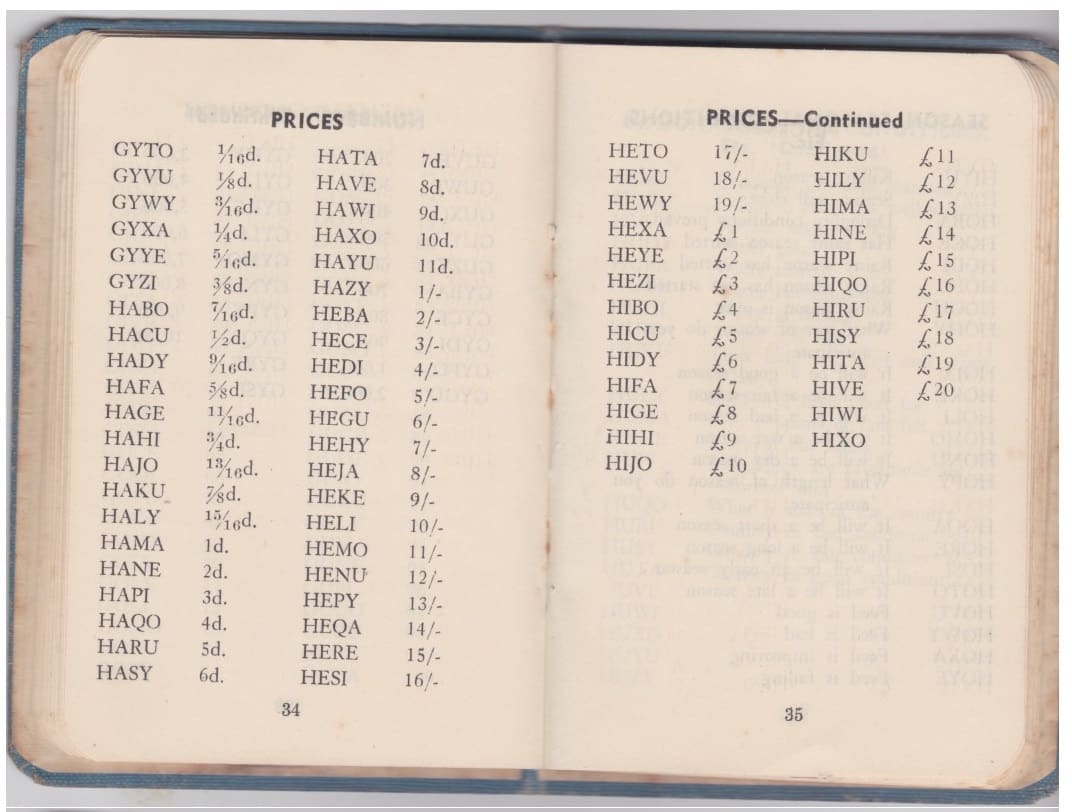

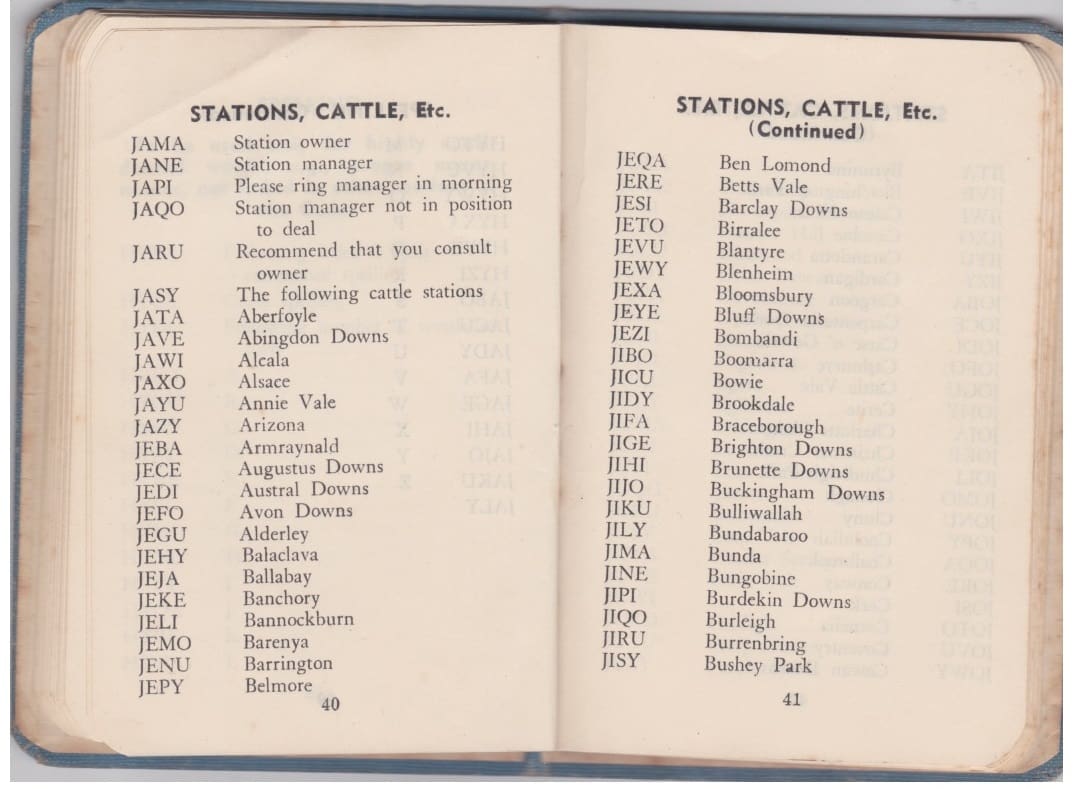

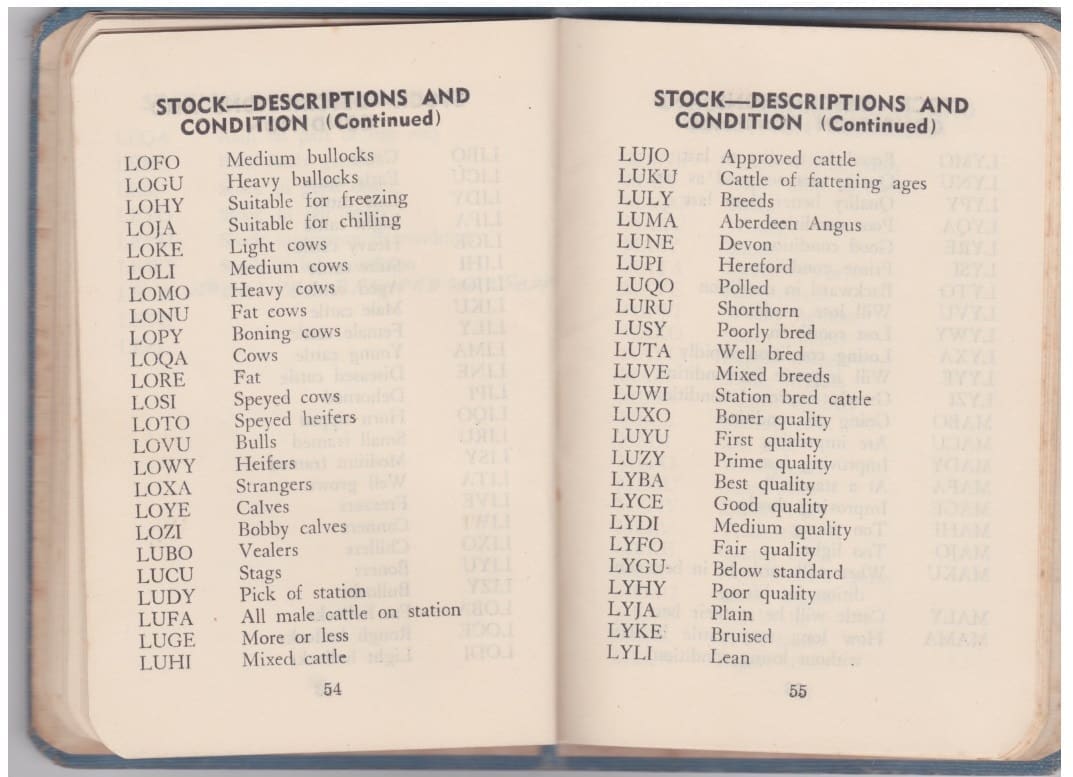

The elaborate series of four-letter codes contained in the book (see examples in scanned images below – click on images for a larger view) ran to 72 pages in length, covering an incredible range of topics from livestock descriptions, price, weight and condition, to buying strategies, agency identities, meat company and wholesale identities, mustering and trucking issues and intentions, delivery dates, and personnel movements. The code book was clearly intended for use Australia-wide.

The list of stock and station agency identification codes, alone, ran to 109 entries. Some are well-known firms that exist to this day, such as Schute, Bell, Badgery, Lumby Ltd; others are long-lost in the sands of time. The predecessors to today’s Elders, for example, are clearly evident, through precedent companies like Elder, Smith & Co; Goldsborough, Mort & Co; Australian Mercantile Land & Finance; Australian Estates; and MacTaggarts Primary Producers Co-op.

Property names, alone, run to more than 15 pages.

In a sharp contrast with today, just five breed-types are referenced in the codes: Aberdeen Angus, Devon, Hereford, Polled, and Shorthorn.

The fact that the code book comes from the period soon after WW II suggests there may have been a military connection in its development, in encrypting messages in such an elaborate and organised way.

Similar code books were apparently in use among other meat companies, and the fact that the codes and code books were frequently changed suggests the process was taken seriously by all involved.

By the 1950s, telephones became more widespread, and the need for secret coded messages started to dissolve.