THERE are compelling reasons why beef cattle will remain critical to not only feeding the planet but also protecting it, a global livestock conference was told overnight.

The Alltech One conference held annually in Lexington, Kentucky, is one of the world’s largest annual livestock industry gatherings, typically attracting 3500 attendees from more than 70 countries.

This year the week-long event which involves dozens of expert speakers has shifted entirely online, which has seen more than 21,500 people from 126 countries register.

Day one presenters who spoke overnight Australian-time included former NASA astronaut and US Air Force colonel Cady Coleman, who shared her recent experience spending 180 days working on the International Space Station to emphasise the importance of teamwork and staying focused in challenging circumstances, a timely message as the world grapples with a global pandemic.

‘Ruminants are not going anywhere’

Dr Vaughn Holder addressing last night’s (Australian time) Alltech One virtual conference from Kentucky.

Another session of key relevance to Beef Central’s readership featured Alltech’s ruminant research group director Dr. Vaughn Holder, who provided a range of critical insights into the actual environmental hoofprint of beef, which contrasts dramatically with the tone of public messages suggesting beef is bad for the environment.

Posing the question “Will Beef Survive?”, Dr Holder said the answer was that “it absolutely has to”.

As the global population grows by another two to three billion people in the next 30 years, our world will have to produce as much food in that time as has been produced in 10,000 years of human civilisation so far.

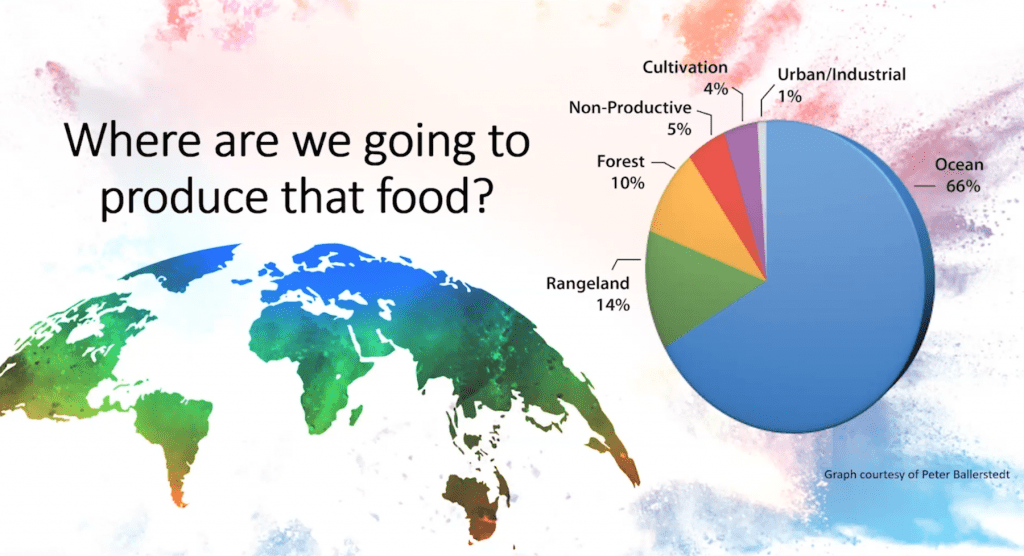

Where will that food come from?

All images from slides courtesy of Alltech One virtual experience conference.

Only 4 percent of the earth’s surface is cultivatable, and able to produce plant based foods such as grain and soybeans.

Expanding aquaculture in our oceans will provide part of the answer.

But utilising the large swathe of cellulose that exists across global rangelands, which can only be converted into highly digestible, highly utilisable sources of amino acids by ruminant animals, will be central to the solution of meeting rapidly increasing world food demand in future.

“There have been many experiments that have tried to convert rangeland to cultivatable land and those experiments have not been very successful,” Dr Holder said.

“Cellulose is the most abundant utilisable carbon source on the planet, and to get the energy out of that carbon source the world needs ruminant animals.

“That is why I say ruminants are not going anywhere.”

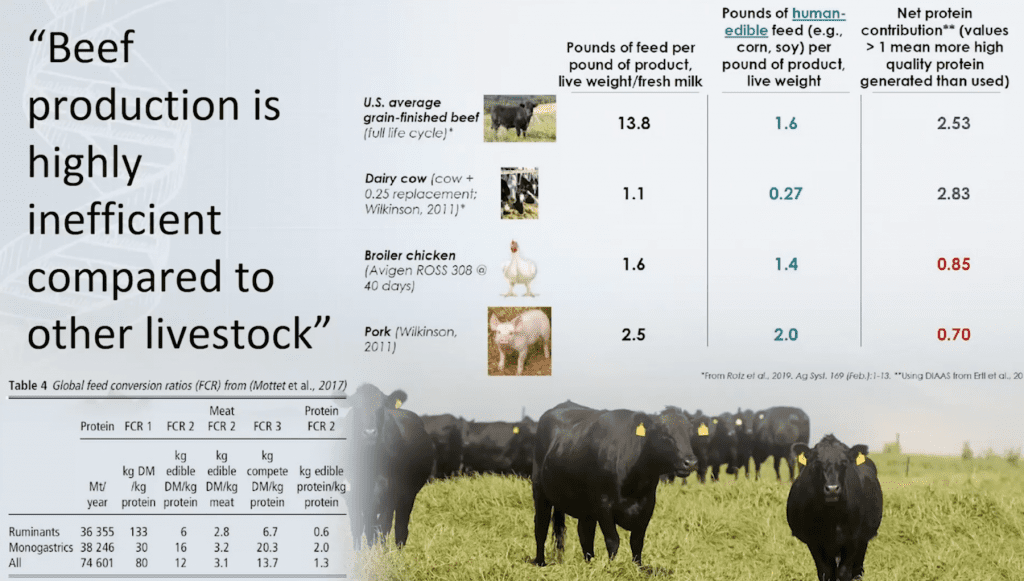

Often-made claims that beef production is highly inefficient compared to other livestock also failed to stack up under closer scrutiny, he explained.

“When you look at pounds of feed produced per unit of product coming out (as shown in table in slide below) you can see beef takes 14 pounds of feed to produce 1 pound of beef,” he said.

“But 12 pounds of that 14 pounds is grass, something that none of other species on this list can practically use.”

Only ruminants can ‘upcycle protein’

In terms of human edible protein per unit of liveweight (as shown in the middle column of the table above) beef is in fact in almost as efficient as poultry.

And when it comes to “net protein contribution” – in other words ‘does the animal make more quality protein or more quantity of protein than what it consumes?’ – only beef and dairy cattle are positive, meaning they produce more protein than they actually use.

“So you can see that when we’re trying to increase the quality of the food we produce that ruminants are king in that space and are actually far more efficient than other agricultural species.

‘when we’re trying to increase the quality of the food we produce ruminants are king in that space’

“This is what I have been talking about, only ruminants can upcycle protein.”

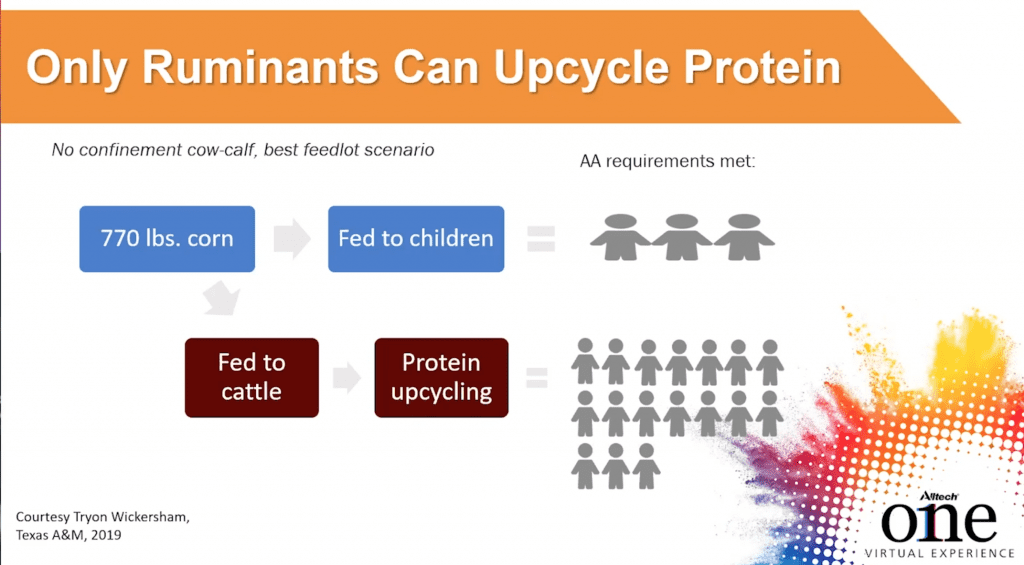

Another question he considered was how much plant based food such as corn would it take to feed people for an entire year?

A Texas A&M paper released last year examined how much corn would it take to feed three children for a year.

It estimated 770 pounds of corn would be required to actually meet the amino acid requirements of those children.

“If you went and fed that 770 pounds of corn to cattle through the protein upcycling effect, in other words they have that rumen, that very special place that converts poor quality feed materials to high quality feed materials, you could then go and feed far more, up to 13 children, on that same raw material.

“This is what we call protein upcycling and is one of the reasons why cattle are so important when we try to feed our populations.”

Dr Holder said the world cannot feed its population moving forward without ruminants.

Methane claims against cattle are overblown

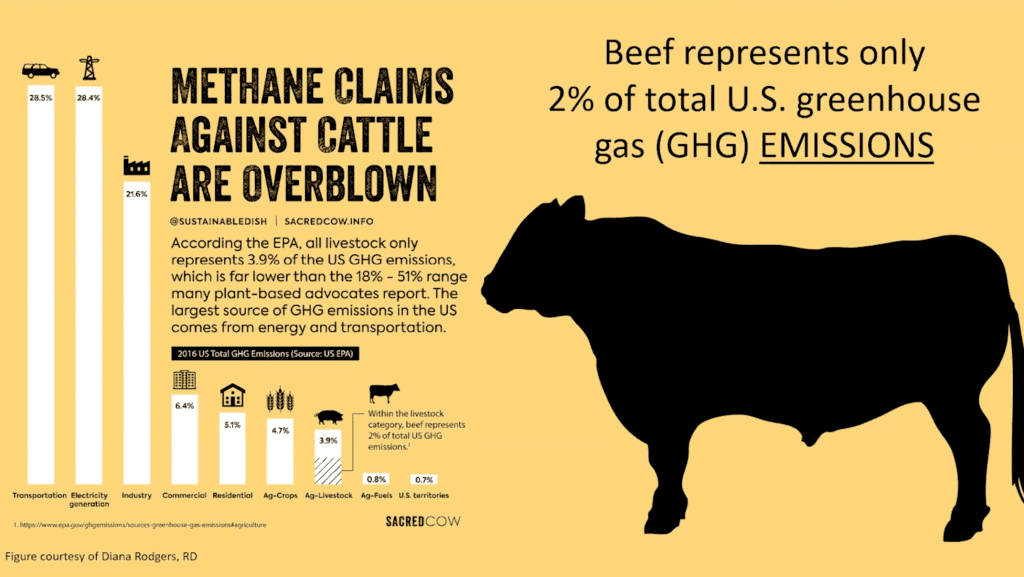

He also looked more closely at the common claim that contribution to greenhouse gases makes cattle bad for the environment.

Plant-based advocates typically claim that 18 to 51 percent of greenhouse gases are produced by livestock. However official numbers from the Environmental Protection Agency in the US place beef’s contribution at closer to just 2 percent, with most emissions coming from transportation, electricity generation and industry.

But nor was that the whole story.

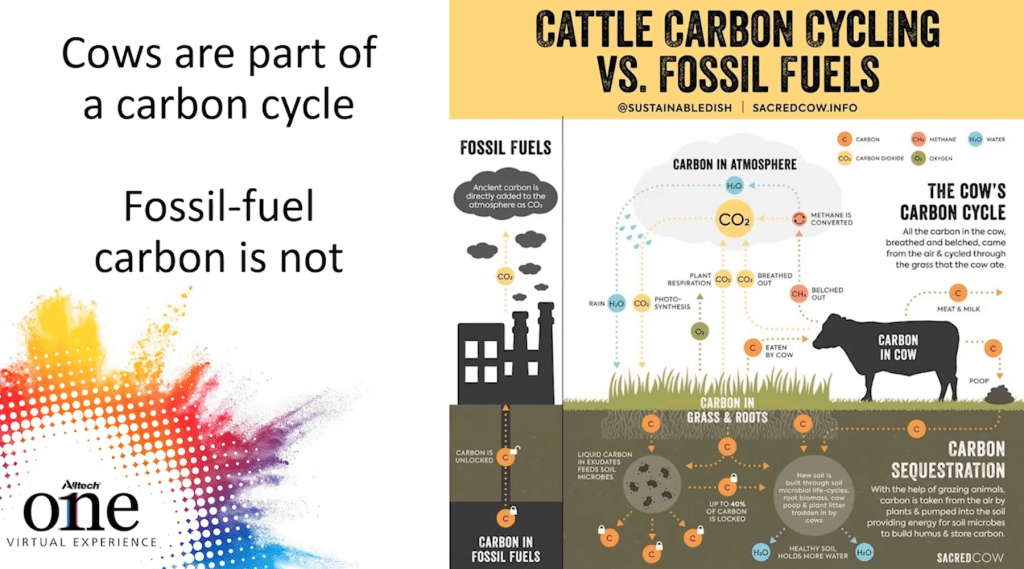

Comparing greenhouse gas emissions from the fossil fuel industry with greenhouse gas emissions from natural organisms like cattle were not the same thing, and in fact were very, very different.

“The carbon cycle of cattle is just that, it is a cycle,” Dr Holder explained.

“There is endless cycles of both photosynthesis taking in carbon that is emitted into the environment, and fixing it, it then being eaten by the cow.”

This was very different to the ‘one-way highway’ of fossil fuel emissions, in which there was no ‘cycle’.

“This is I think is the main problem that we miss when we talk about emissions versus total contribution to the potential for warming from these emissions.”

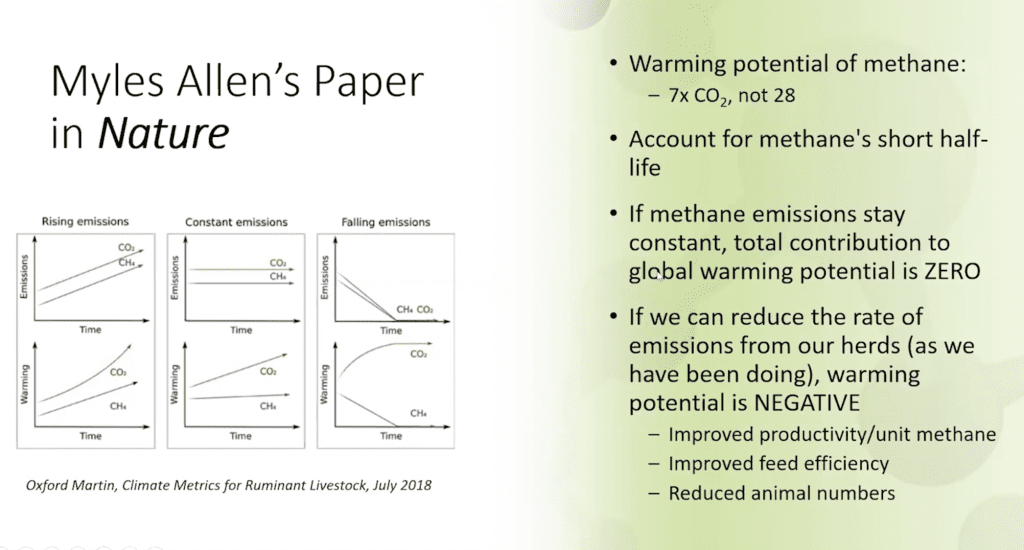

There was also growing recognition that emissions impacts need to be viewed from a total lifetime perspective, such as some of the research recently led by Myles Allen, head of the Climate Dynamics group at the University of Oxford’s Atmospheric, Oceanic and Planetary Physics Department and published in Nature in 2018.

While CO2 emissions accumulated in the environment, a reduction in emissions from cattle resulted in an immediate reduction in warming potential.

“Now this is really valuable because there are very few industries that have the ability to reduce warming potential or to produce cooling potential and ruminant agriculture is probably one of the most promising ways of doing that.”

Dr Holder said the beef cattle industry has made significant advances in improving feed efficiency and reducing the intensity of its emissions per unit of production in the past 30 years, but had failed to communicate that message.

“Our emissions intensity per unit of product is 32pc down since 1961, that is the real message we need to get out there.

“We are constantly on the negative end of all of this press but we are actually contributing to a reduction in warming potential with our farming practices focusing on feed efficiency.

“If we could bring the efficiency of production of beef across the world to the same level it is at in developed countries we would reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of those systems by 45pc and still produce the same amount of beef.”

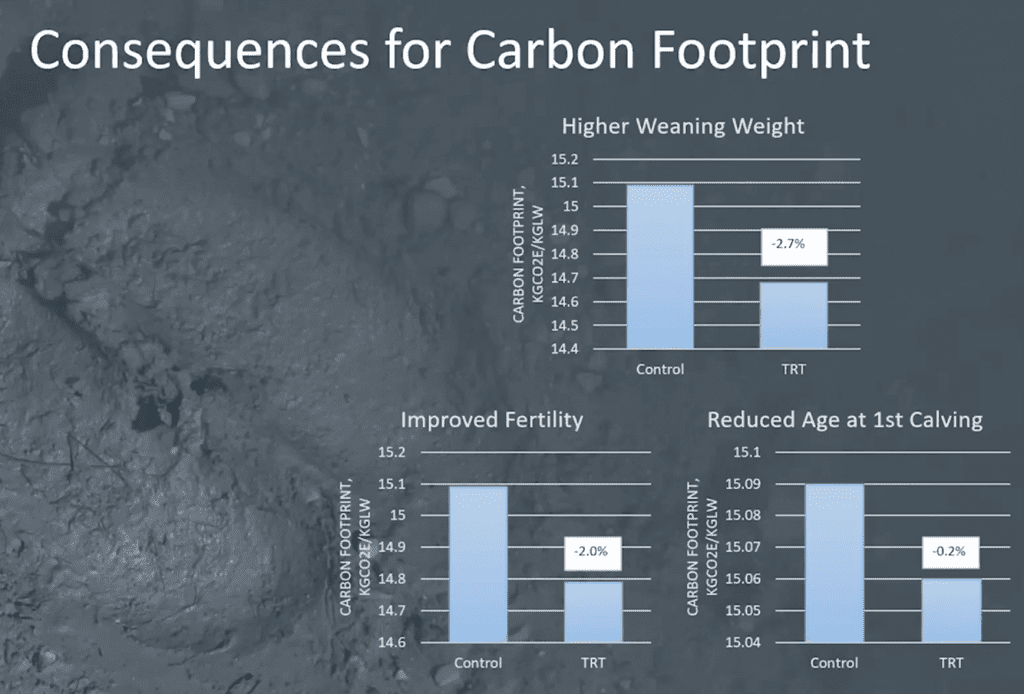

Dr Holder said his team recently reviewed a range of past research trials through a new lens: to consider what achievements in feed efficiency actually meant in terms of reducing of global warming potential.

This included studies of trace mineral interventions to increase weaning rates, improve fertility and reduce age at first calving which confirmed a combined 5 percent reduction in the carbon footprint of beef cattle.

Also examined was a summary of 14 different trials of Alltech’s enzyme supplement Amaize used to improve carcase weight in beef cattle. The studies showed an average production response of 15.5 pounds, well above the hot carcase weight break even requirement of 1.3 pounds. This in turn resulted in a 3 percent reduction in the carbon footprint of those feedlot cattle.

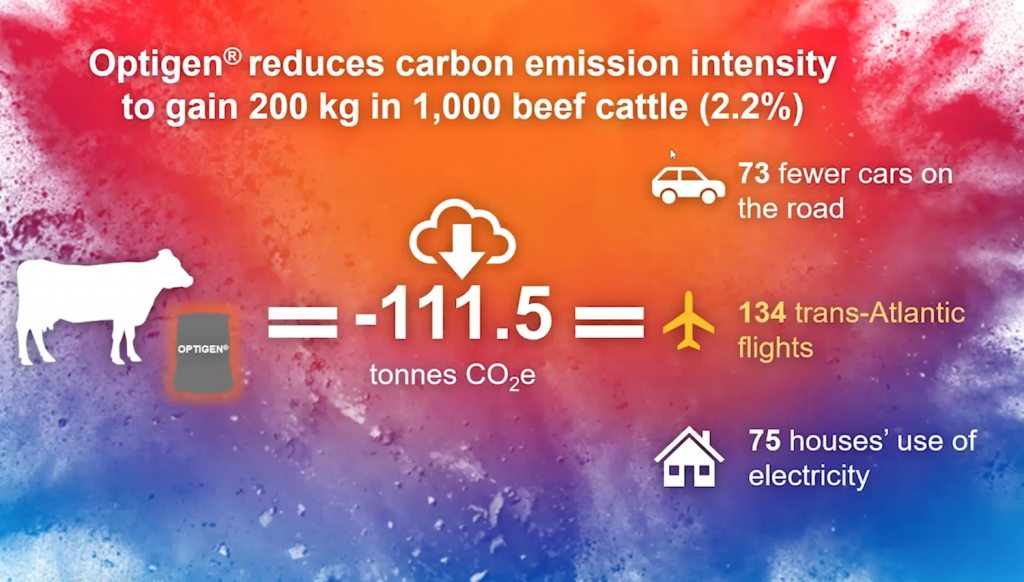

A third example involved a meta-analysis of the Optigen slow-release nitrogen supplement in beef and dairy cattle which showed improvements in liveweight gain and feed efficiency in growing and finishing cattle.

The relatively minor changes in feed efficiency achieved in all three examples led to quite dramatic changes in carbon footprint, Dr Holder said.

Across 1000 head of beef cattle the reductions were the equivalent of removing 73 cars off the road, or 134 transatlantic flight tickets or 75 house’s electricity use.

“These aren’t small changes we are making here, but this is not something that we have particularly looked it in the past,” he said.

“It is looking at these feed efficiency interventions from a carbon footprint standpoint.

“And this is something we need to start doing and start doing aggressively and perhaps most important, start to market ourselves that way, because we have been using technologies – not just in feed technologies, but management and efficiencies – for the past 30 years that have dramatically reduced the carbon footprint and dramatically improved the feed efficiency of our operations.

“And we should be owning that because that is something we can all be proud of.”