THE United States is shaping up to play a critical role in demand and price for Australian export beef in 2024 – albeit a year later than what many had originally anticipated.

Making his annual visit to Australia this week as part of Meat & Livestock Australia’s preparations for annual industry projections was US red meat market analyst Len Steiner. For more than 25 years Steiner Consulting has provided regular US market intelligence for the Australian beef industry.

Len Steiner

While US cow slaughter was now down somewhat compared to where it was a year ago, driven by prolonged drought, the decline was not yet dramatic, Mr Steiner told a briefing held in Brisbane yesterday.

That was primarily because US cow calf producers were still being financially incentivised to send cows to slaughter, rather than begin herd rebuilding, after years of drought.

“They are thinking the money in their pocket today (cows sold for slaughter) is better than money in their pocket two and a half years from now (revenue from calves sold),” Mr Steiner said.

The aging producer population in the US may also be influencing such turnoff decisions, he said.

One of his producer acquaintances in Nebraska who was running 2500 breeding cows two or three years ago, had no cattle at all today, turning his entire herd into cash.

“Calf returns are inevitably going to be very high in coming years, but so far that has not incentivised US cow-calf operators to stop liquidating females,” he said.

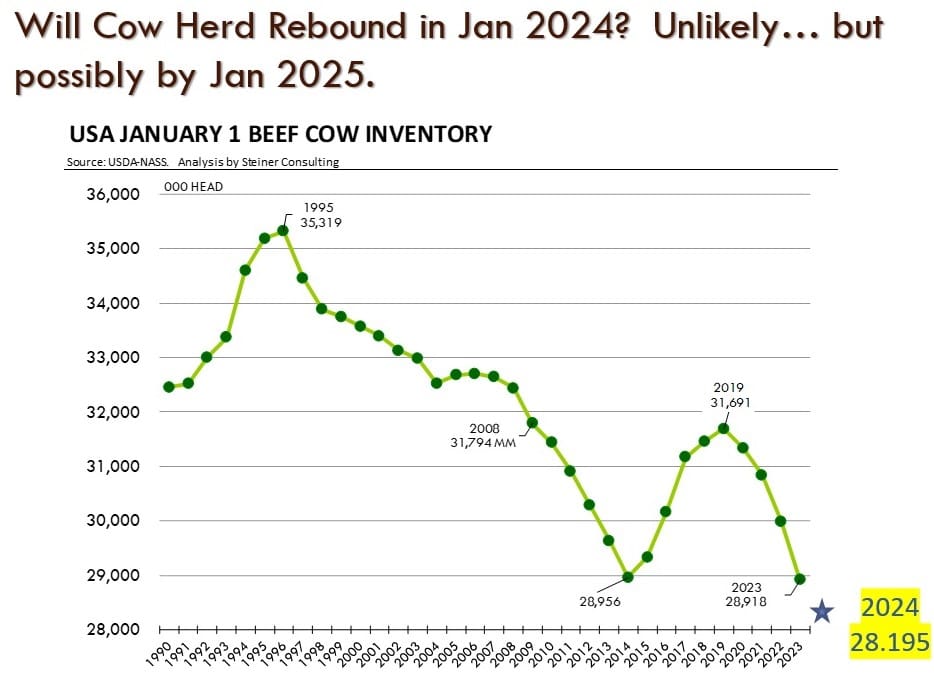

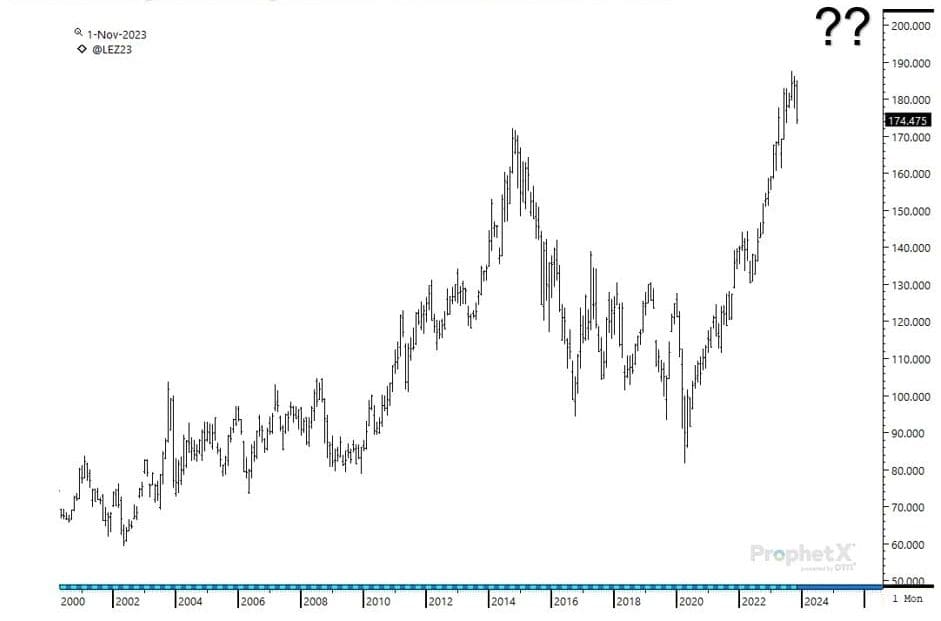

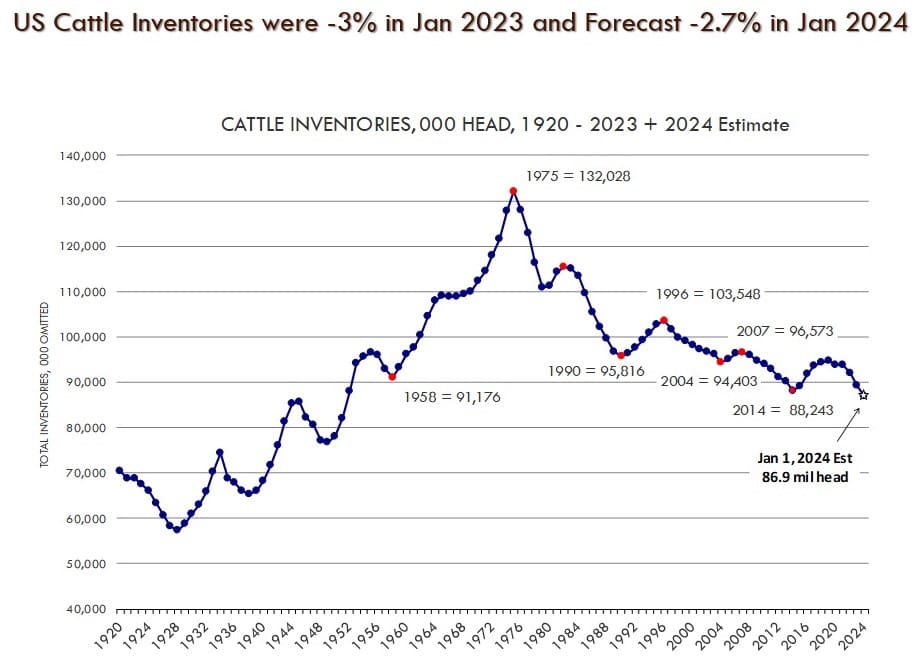

Mr Steiner said the US cow herd was unlikely to show any signs of rebound in the USDA’s upcoming January 1 national herd survey, meaning any start might not be evident until 2025 (see graph at top of page).

“Sitting here in Australia a year ago, I would have said the US herd rebuild would start in 2023. That hasn’t happened, it’s been significantly delayed.”

Mr Steiner said on January 1 next year – a month from now – the USDA survey was likely to show a US cattle herd (all cattle and calves) of about 86.9 million head – the smallest number seen since the 1950s. That number, if proven correct, would be down another 2.7pc on top of a 3pc fall last year, with beef cow numbers at 28.2 million head, down another 2.5pc.

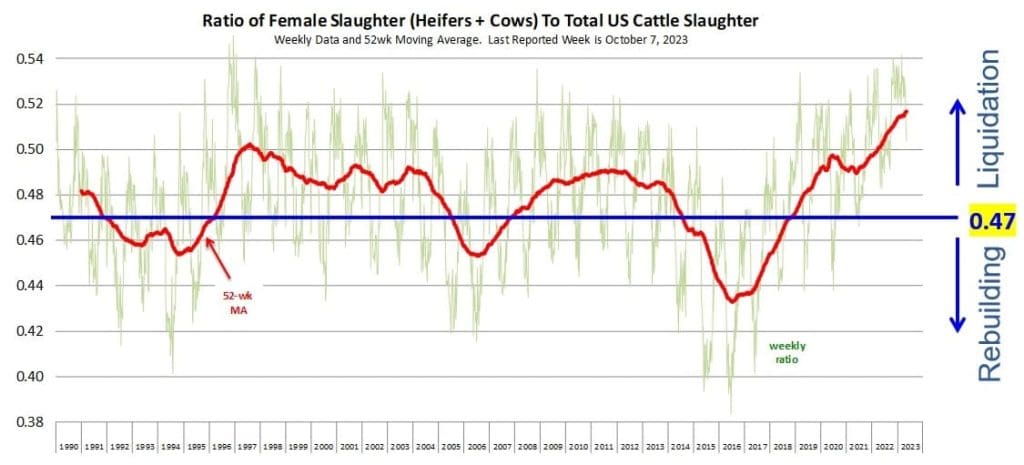

Female slaughter ratio

Using a 47pc female slaughter ratio as the US indicator of the tipping-point between herd expansion and contraction (Australia uses a similar metric), Mr Steiner said the US beef herd remained strongly in liquidation phase at this point. He said it was currently not a question of when US herd rebuilding would start, but when liquidation would end.

“By rights we should be in a rebuilding phase by now, but we are still in liquidation,” Mr Steiner said. “It’s very odd – feeder cattle prices have risen dramatically, and yet we continue to put more females into feedlots, rather than back into the cow herd.”

“It’s absolutely unsustainable – something has to change, otherwise the US will not have a cow herd left.”

Any further delay in commencement of US herd rebuilding would only further limit US beef production in coming years.

Any further delay in commencement of US herd rebuilding would only further limit US beef production in coming years.

The trend in average carcase weights in US slaughter cattle was only compounding the US beef supply problem next year, Mr Steiner said.

Since about 2017, the relentless increase in US beef carcase weights has slowed down, and indeed declined. That was partly because US steer carcases (averaging above 920 lb or 415kg in the recent past) got too big for end-users to handle, meaning lotfeeders producing the heaviest carcases suffered ‘tremendous discounts’ from packers who found it hard to place the beef.

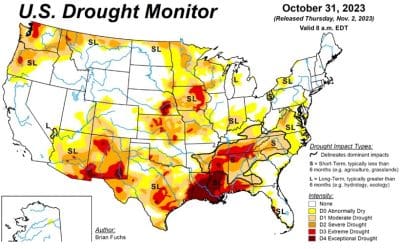

Drought impact still being seen

While the extreme drought seen last year had lifted in some US cattle producing regions, drought impact continues in some parts of the US this year, with pasture conditions well below average, as can be seen in this colourised map compiled 31 October.

Fed cattle prices retract, on consumer response

US fed cattle prices had this year blown out to all-time record highs, but over the last few weeks had taken a sharp dip, Mr Steiner said.

A key reason was that US packers were not able to get enough money for the meat (consumers were backing away from beef prices) to justify record feeder prices.

This had forced US packers to lower prices for fed cattle sharply in recent weeks to try to maintain a margin.

“Retail and wholesale beef prices had been tracking the rising cattle price trend this year, but at some point, US consumers said enough, and started to move to other options. The threshold was found. There was much more resistance to higher beef prices than I had expected,” Mr Steiner said.

US fed cattle prices: How high is high in 2024 and 2025?

The US beef cutout versus pork cutout had shown that the American public had been prepared to pay a bigger and bigger premium for beef over the past year.

“American love their beef, and are prepared to pay up to get it – but they are clearly not prepared to pay unlimited amounts of money. If the economy tightens up and consumers don’t have as much money to spend, certainly beef is going to take a price and demand hit – and has done recently.”

Sharply rising livestock prices had also made it increasingly difficult for the US to compete in export markets.

The wider the spread between the cutout and live cattle prices, the more money US packers made. While packers were ‘printing money’18 months ago, that had changed dramatically as US livestock prices had risen this year, and was likely to continue to be low next year, Mr Steiner said.

While US consumer confidence is down, dollar sales at retail and food service (restaurants, hotels, pubs and clubs etc) are now well above pre-COVID levels, Steiner data showed.

Total US meat production down

Domestic meat and poultry supply (comprising beef, pork chicken) in the US had basically stalled since 2019, Mr Steiner said, with some shift from beef into other proteins. That trend was forecast to remain much the same through to 2025.

“Raising animals for meat was basically a growth industry in the US for the previous four decades, but it looks like it’s stalled, at this point,” he said.

We’ve just slowed the production of all meat, and the biggest shortfall in 2024-25 is going to be in beef,” he said.

Mr Steiner said he believed that long-term (perhaps 25 years from now) the US cow-calf industry would go the same way that that US chicken industry had done: aggregation of smaller enterprises. There were still plenty of ‘lifestyle’ US beef herds running only 12 or 15 cows, he said.

“In pork, it’s been about getting big, or getting out – there’s no in-between. I think cow-calf operations will go the same way. New York bankers will probably be the guys putting up the money to make that happen.”

Globally – more people, less cattle

Mr Steiner said with the exception of Brazil, all major beef producing countries in the world – including Australia and the US – had cattle inventories below their highest number for the past ten years.

“Put simply, the world has more people, and less cattle. The beef industry is getting to become a specialised commodity. With the exception of Brazil, the global industry is not keeping up with population growth.”

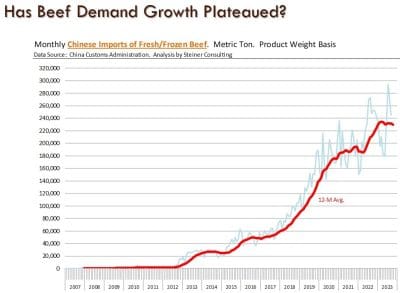

Economic conditions in China appeared more fragile than they were a year or two ago, and it looked like the surge in demand for beef from China that started from a low vase in 2013 had now flattened out.

“China has certainly been a big global buyer of beef – more so from Argentina and Brazil than Australia – but when other markets (like China) are exhibiting high demand for beef, Australia ships to those markets. But when things (global demand) slows down, America typically becomes their best friend again,” he said.

In terms of Australia’s export competitors, Brazil had continued to ship more beef into the US this year, but was hampered by very modest quota access.

“The Brazilians are willing to pay the considerable out-of-quota duty to get product in, so Australia has a distinct competitive advantage in the US in this, because of the size of the tariff free quota. It’s been a long time since Australia has gone close to filling its own US quota.”

Because of that trade access, Australian cattlemen were better off, because with ocean freight rates coming down and no tariff or quota barrier to contend with, it provided a significant advantage to Australian exports.

As the US industry produces less beef, exporters (like Australia) tended to get a bigger discount over domestically-produced manufacturing beef. This is due to production cost advantages in using certain amounts of frozen imported trim combined with fresh domestic US trim to produce ground beef for burger patties.

For 2023, year to date, the discount on imported 90CL sits around 25pc, and is likely to be ‘in this vicinity’ in 2024, Mr Steiner suspected.

Steiner’s price forecasts for 2024 included imported 90CL cow beef into the US almost 28pc higher than the average price seen in 2023, at US280c/lb.

- As US beef supply inevitably shortens up during the second half of 2024, some unusual prospects may emerge for Australia, including a greater proportion of grainfed chilled primal cuts exports – especially round cuts – versus Australia’s principal US trade in frozen manufacturing beef used for burger patties. More on Len Steiner’s views on that topic in a separate story tomorrow.