AS THE two-year milestone approaches since the introduction of the industry’s Eating Quality Guaranteed beef cipher, frustration continues to circulate among some producers over the slowness of change towards the describing meat on its predicted eating quality, instead of the number of teeth an animal has.

Dentition has been the universal measure of maturity, and a proxy for meat quality, for decades, but 2017 saw the introduction in Australia of a radically new, optional cipher based on MSA eating quality index scores (click here to view original story).

EQG provides the option to focus just on consumer outcome and let carcases be graded on their quality attributes as predicted by MSA, regardless of how many teeth the animal had.

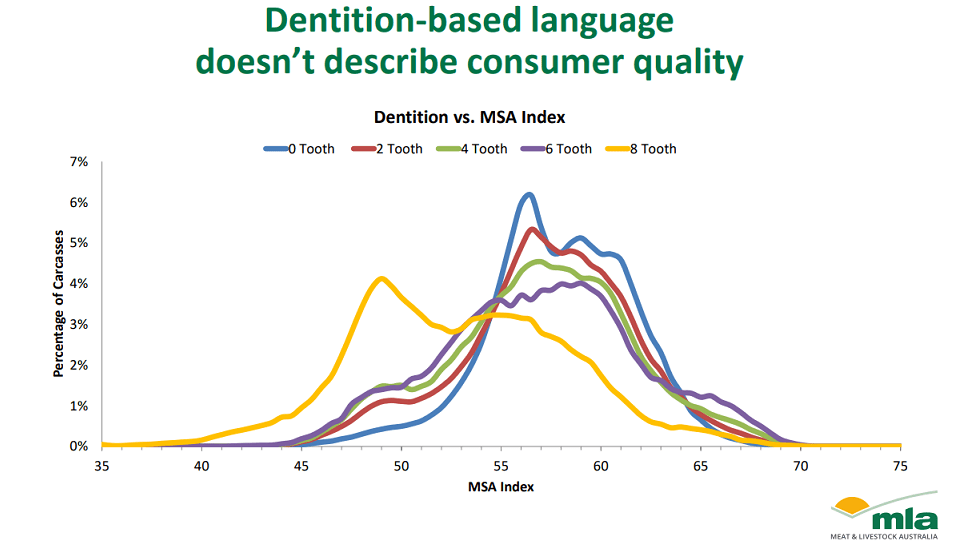

The graph published below, produced by MLA, represents more than two million animals that have been MSA graded, that also had dentition information collected.

It plots MSA Index (as a measure for eating quality of animals) divided into each dentition category. The plot lines clearly illustrate that dentition is not a great indicator of consumer eating quality, as there is a large range in eating quality variation within each dentition group. And the dentition groups largely overlap: for example a six-tooth animal could share the same eating quality, or better, than a milk-tooth animal.

Central QLD grassfed case study

The examples of lines of slaughter cattle where older animals in the mob have produced good to excellent MSA eating quality scores, but have been harshly treated in meatworks grids because they have fallen outside the target range on dentition are legion.

Here’s yet another good example, generated just weeks ago by a line of British-based certified grassfed steers heading into a brand program, slaughtered in Queensland in June.

Vendor, and Rolleston beef producer, Ian McCamley, described the mob’s performance like this:

The mob of 125 steers included a majority with four teeth, but included some twos and sixes, and a single animal with eight teeth. The lone eight-tooth steer in the mob was the only carcase to make Teys Boning group 1, based on MSA grading, producing an Ossification score of 120 and an MSA index of 63.86.

The eight-tooth steer fell out on company grid specs on dentition, however, making 515c/kg. The animal with the least teeth in the mob had one tooth. He made Teys Boning group seven, also with an Oss of 120, and an index score of 55.82.

“That’s 8.04 MSA index points less than the eight-tooth steer, yet he made 575c/kg on the grid,” Mr McCamley said.

Interestingly, of the three McCamley steers that made boning group two, one had four teeth, and the other two, six teeth, for no premium.

This example is not intended to criticise Teys in any way – indeed the company is one of the early adopters of the EQG index in some of its programs – but is designed to illustrate the inefficiencies and waste that is slipping through the broader beef supply chain through reliance on dentition.

“All that time and effort by good people, plus hard-earned producer levies to get the EQG cypher up, and a steer producing an MSA index of 63.86 gets smashed because he had eight teeth. Crazy stuff,” Mr McCamley said.

“There’s definitely a sense of frustration,” he told Beef Central.

“One big impediment I see is in the lack of adoption among the major domestic supermarkets. They are still locked into the mentality that milk and two-tooth cattle have got to be better, and the science is just belting that out of the park all the time,” Mr McCamley said.

“One of the frustrations, currently, as a grassfed finisher is that we have to be mucking around with cattle all the time, checking teeth, when our recent kill results again clearly show that is unnecessary. The supermarkets should be taking the lead on this – they were once the real innovators and early adopters of new systems in the beef industry, in so many ways.”

Mr McCamley said processor meat salesmen inevitably sought the ‘path of least resistance’ in their dealings with customers in Australia or overseas. “They don’t want to have to go out and try to convince the market to do something differently, having bought beef a certain way for years and years.”

What progress has been made?

So how far has the industry come since EQG cipher was introduced back in 2017?

Industry data shows that at the end of 2017/18 businesses (processors and independent brand owners) that had adopted EQG in some way, represented 27pc of MSA grading volume.

During the past 12 months ended June 30, there have been more supply chains adopt the new cipher. It is estimated that when data is produced for the full 2018/19 year just completed, those businesses using EQG in some way will represent around 47pc of MSA grading volume.

That represents an increase of 20 percentage points, year-on-year.

Worth noting, though, is that this percentage value does not necessarily mean everything that has been MSA graded by that company will have an EQG cipher applied. It simply represents the volume of MSA product being produced in operations that are utilising the EQG cipher as some part of their business.

The message in this is that EQG cipher uptake continues to grow, but perhaps not quite at the rate that some stakeholders would prefer.

Processor/exporter views

Teys Australia’s livestock general manager Geoff Teys said his company had adopted the use the EQG cipher in some programs, but pointed out that market restrictions still limited its use. Beef entering the EU market, and even bone-in beef into Japan, for example, had to be sold under dentition-based ciphers.

Geoff Teys

Much of it had to do with BSE safeguards around the world, with beef from animals four-teeth and less considered a lower-risk than older cattle.

But equally, in markets where it is allowed, some Teys customers were receptive to an eating quality based system, and had responded favourably to the move.

“We’re working as hard as we can on it, but there are cultural challenges in changing the way beef has been traded internationally for decades,” Mr Teys said.

Teys’s chief value chain officer Tom Maguire said certain export markets still insisted on trading on dentition.

“But it is gaining a foothold in markets like the US, Japan and domestically,” he said.

“Volumes and the number of customers prepared to trade on the EQG cipher are definitely growing, as they better understand the process,” Mr Maguire said.

“But the issue is that, until we get almost full uptake of a system based on eating quality, we cannot manage dual systems, and cannot simply turn off the dentition-based programs,” he said.

“But we are well and truly on the way.”

“Should we be able to just sell beef based on eating quality? Absolutely. But until we can get global acceptance for it, we’re in this awkward transition, and it’s very hard, if not impossible for a processor to operate under two (sorting) systems.”

He also pointed out challenges surrounding different parts of the carcase going to different markets.

“It’s fine to segregate the MSA grilling cuts as EQG, but what happens to the value of the rest of the carcase? Say rumps, strips, cubes and tenders are sold under MSA with an EQG cipher, but what happens to the rest of that body, if it cannot be sold as EQG? It may be rendered ineligible for certain markets unless it has a dentition-based cipher attached to it. And for secondary cuts like rounds or knuckles that are universally sold under dentition, it’s a real challenge to try to convince customers to buy under another system.”

“Effectively, all the secondary cuts may have to default to ‘eight teeth’ – the worst-case scenario – unless their dentition is identified.”

NH Foods is another large processor which has adopted EQG in some of its branded programs.

“It’s got plenty of potential, but it’s still early days,” said the company’s marketing manager, Andrew McDonald.

“Some buyers are crossing over, but it takes a while to explain the changes to customers, and for them to be comfortable to move away from buying systems they have used for decades.”

He said where it could, NH Foods Australia was actively encouraging customers to consider buying on EQG rather than dentition ciphers.

“The customers who have visited our plants and seen the process in action, now understand how it works – and they get what’s going on. They understand there are quality controls in place, and what does an ‘A’ or an ‘S’ or a ‘PR’ on the side of a box really mean in terms of meat quality?”

Mr McDonald said that one challenge was that some large end-users typically bought from a number of supplier countries, and using a different set of criteria for Australia from New Zealand, Uruguay or the US could raise its own challenges.

He saw the domestic market was potentially an ‘easier target’ for EQG adoption than export, especially in the early stages.

Supermarket position

On the domestic market, neither Woolworths nor Coles have adopted the EQG cipher in their beef operations to this point.

Both continue to apply a 0-2 tooth spec on cattle fed for their programs, although in the case of Woolworths, it now accepts four-tooth cattle that have broken teeth during the lotfeeding phase, without a price penalty. The company stresses, however, that this is not designed to ‘encourage’ suppliers to produce more four-tooth animals, but simply applies to try to avoid discounts on cattle that have just broken their third and fourth teeth.

Woolworths argues that while a move to EQG cipher might deliver a piece of meat of equal tenderness, it ignored other attributes which it considers important to the supermarket retail customer, like meat texture (it argues that texture tends to become more coarse in older animals) and meat colour, which it suggests tends to darken in older animals.