AN important new piece of statistical research has challenged widely-accepted numbers around Australia’s national beef herd size, suggesting the previous estimates may have been dramatically under-reported since the mid-1970s.

The report, titled Australian cattle herd structure, live weight and carcass production, 1976-2018, and associated reproduction, survival and growth, was written by recently-retired QAFFI research scientist Dr Geoff Fordyce, with collaborators including Dr Mike McGowan from University of Queensland, animal health consultant Dr Richard Shephard and Tim Moraveka from Queensland’s Department of Agriculture.

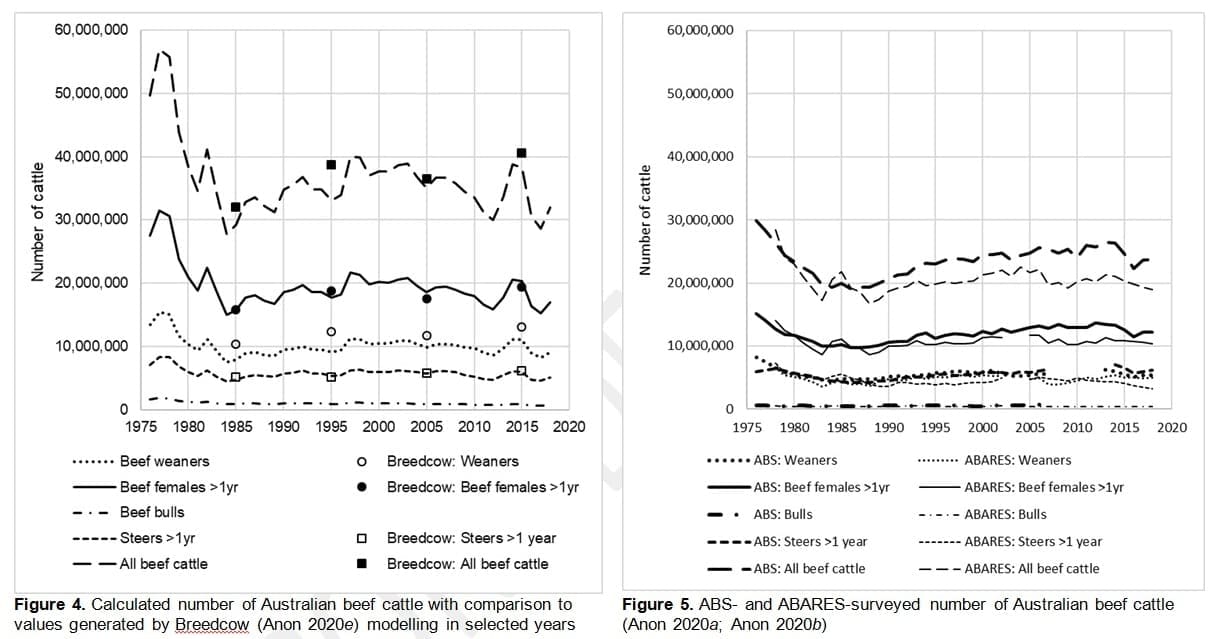

Using a herd model that reconciled beef and dairy herd performance against 1976-2018 slaughter and live export statistics, Australia’s beef herd was calculated in the study to be consistently within a range between 30 million and 40 million cattle for the past 35 years – not the 25-29+ million head widely reported and accepted around the industry. The calculated figures equated to 12-16 million tonnes liveweight, and averaging 14 million tonnes over the past 35 years.

These startling results may alter how future survey data is collected, analysed and then used by beef businesses and research and advisory agencies working with the beef industry. It raises questions not only around the nation’s true beef herd size and levels of fertility and productivity, but also around environmental and emissions claims made by the industry.

The project’s main conclusion was that the size, performance and productivity of the Australian cattle herd are quite different to that portrayed by existing survey data, and that future analysis can be altered by implementing alternate survey methods to combine with accurate statistics to more accurately derive existing herd parameters.

The research also identified on-going opportunity to derive benefit from improving cattle survival, reproduction and growth and from sustaining and improving the feed base.

The conclusions in the paper may go some way towards explaining the frequent use of terms like ‘the phantom herd’ around the industry, to explain unexpectedly large numbers of slaughter cattle coming forward, after periods of sustained drought and herd liquidation.

Background

In prefacing his work, Dr Fordyce said that during the development of the Northern Breeding Business (NB2) program, an initiative developed by MLA to address calf loss in northern breeding herds, low profitability of many northern beef enterprises, and low adoption of proven management practices and technology, he had looked for an accurate description of north Australian herd performance and production.

“The obvious place to look was ABS and ABARES publications. This revealed some inconsistencies, especially that what surveys suggested were cattle numbers was clearly an under-estimate,” he said.

“This was alarming, as most in Australia and internationally take these data from these reputable sources on face value. But it also matched the ‘gut feeling’ of many in the industry that there are a lot more cattle than the surveyed businesses were admitting to.”

Dr Fordyce said that until he had accurate basic data, he could have no faith in any calculations done with the information.

“Despite what most were thinking, no-one had taken ABS data and tried to reconcile it, as it is not an easy task. So I set about doing it – it took me four months part-time, but in the end I was able to achieve my objective, to describe the structure of the herd, and its performance and production.”

The key factor that enabled him to perform the task was the large north Australian Cash Cow fertility project conducted on commercial cattle stations over a number of years, providing the key data to link with what ABS could provide.

“Without Cash Cow, this work would not have been possible,” Dr Fordyce said.

Up to this point, MLA or any industry stakeholder wishing to analyse the national beef herd for future trends or for establishing opportunities and priorities, have had to use a modelling approach built on ABS and ABARES data. (MLA sets out its current methodology in assessing herd size, and a brief response to the Fordyce paper, in comments further below in this article).

“Some of this data is fine – what I call statistics,” Dr Fordyce said. “This includes slaughter numbers and weights, live export numbers and weights, and feedlot populations. But survey data derived from what producers with no obligation to tell the truth have told them, has significant inaccuracies and more specifically, significant under-estimates.”

Having done the calculations and realising what they contained, Dr Fordyce published his paper in an international peer-review journal to ensure the accuracy of the methods and results. The paper has now been published and an abstract can be accessed here.

He also consulted with MLA so the primary users of the data could consider appropriately altering their methods and guide changes needed with a new understanding of the herd.

“MLA leadership, including the board, and senior management have been very positive about the findings,” he said.

Benchmarks

In the paper, liveweight production is expressed for each sex as annual production per post-weaning age animal. The definition of liveweight production is the weight change of an animal over a year, plus the weight of a calf it weans.

Another new term used in the study, for many in the industry, is liveweight production ratio.

For example, if a producer has an average of 200 tonnes of cattle in a paddock over a one-year period, and net harvest is 60t (ie, what is sold either directly or indirectly, then the ratio is 60/200 = 0.3). This number is expressed in the report for each sex as kg/kg of cattle.

“The reason for this ratio is that the bottom number (the denominator) is closely related to feed intake,” Dr Fordyce said. “Therefore, liveweight production ratio is a measure of the amount of liveweight produced, divided by a measure of the amount of feed eaten to produce it; ie, it is an efficiency measure.”

The Cash Cow project had shown that cow herds in poorly-efficient businesses could have a LWPR as low as 0.1 kg/kg cattle. North Australian businesses with high efficiency often had levels as high as 0.4 kg/kg of breeding cattle.

Last year, Dr Fordyce and others reported a liveweight production ratio of 0.31-0.32 for well-managed breeding cattle groups grazing the primary country types of northern Australia – just above the value calculated for the national herd at the same time.

“This result is primary corroborating evidence that the only way for the national herd to produce the reported slaughter weight and liveweight at live export, was to have a much-larger herd than that suggested by existing surveys,” he said.

Production of the same predictions for the Australian beef herd performance and production using Breedcow software tools also strongly supported the accuracy of calculations in the new study.

“The inability to construct a model using herd sizes derived from surveys, even when performance parameters are varied greatly, is further evidence that the calculations reported here are accurate,” the report suggests.

‘Truth serum’

The consistent substantial under-estimates of cattle populations by both ABS and ABARES surveys (36pc and 43pc, respectively, since 1980, according to the report) demonstrated the need for survey agencies to ‘apply truth serum’ to their survey data, the report suggests.

“It is recommended that robust models be developed that use known statistics to adjust survey data,” it said.

The basic method used in the research has been in use for at least 35 years, and is a standard strategy used by business analysts and economists to understand beef business they advise in the absence of any reliable data other than sales.

“The power of suitable modelling shown in this study indicates the need for full surveys may be obviated if accurate data for slaughter and live export of cattle continues to be available,” the report said. “Surveys remain valuable in defining relative, rather than absolute values. The precision of the modelling used here was limited by no records of sex x live weight differences in cattle exported live.

If this could be introduced in some form, it would further increase the accuracy of any herd performance and production calculations, the report said.

Available feed dictates herd size

It should be no surprise that the Australian cattle herd has remained within a consistent range for many years, the report said.

“The size of herds is limited by feed available. Unless feed resources change significantly and cost-effectively, it is not possible to increase the herd size. In the 1970s, wild fluctuations occurred in the beef herd which peaked near a calculated 60 million cattle, in contrast to the surveyed (currently accepted) peak herd size of 34 million.

“This cycle reflected extreme market conditions – that is the failure of Australia’s main export beef market at the time – the US – which caused producers to hold cattle from sale for several years. The huge increase in herd size was possible, because the mid-1970s was close to the wettest period in Australia’s past 130 years, thus providing feed to sustain extra cattle.”

Price recovery in 1978 was associated with a major sell-off of cattle, which was enhanced by exacerbated by drought conditions that worsened till El Nino conditions dissipated in mid-1983. From this point, there was recovery to a sustainable herd size.

The report noted that in the dry early 1980s when national herd size fell below 30m, calculated mortalities did not drop to the same degree below the level it was to track at (about 2 million/year) for the next 20 years. In other words, the dry years contributed to a higher mortality rate.

Liveweight production growth

Even though the Australian herd size has remained in a constant range, annual live weight production has steadily increased, the report found. It had grown to about two million tonnes, about 80pc higher than in the mid-1980s.

Over that period, calculated annual mortalities, dominated by females, have reduced lost production by about one million tonnes annually, which explained half of the change. At the same time, calculated reproductive rates and calf weights from the national herd have steadily increased, increasing weaner production by about one third, or about 500,0000t, which explained most of the balance of change in female production.

“Therefore, changes in growth explain a quarter of the production gain, which was confirmed by increased annual liveweight gain by steers being 0.5 million tonnes. The low contribution of average annual female cattle growth to national herd live weight production, because many are slaughtered well beyond maturity and this class contributes most mortalities, indicates most of the benefit of their higher juvenile growth is through impact on male progeny growth,” the report said.

Further opportunity

“Even though there have been consistent improvements in Australia’s cattle herd performance, production and efficiency over many years, the opportunity to increase further appears substantial,” the report found.

This is highlighted by average annual live weight production per animal being more than 40kg lower than annual juvenile animal growth. Liveweight production per animal is higher than annual juvenile cattle growth in an efficient situation. In an earlier research study, Dr Fordyce and others found liveweight production per animal in four well-managed north Australian breeding herds matched or exceeded average annual juvenile cattle growth. Similarly, in another study, well-managed breeding cattle in a south Australian environment in which yearling growth exceeded 200kg achieved liveweight production of about 240 kg/animal at an efficiency of 0.3kg/kg of cattle. A 1975 US study also demonstrated that well-managed US cattle herds where average annual juvenile growth approached 300kg, had liveweight production in the vicinity of 350kg/cow.

“The relative contributions of mortality (about half), reproduction and growth (about a quarter each) to continually-increasing national production are a clear guide that improving each will continue to improve production and efficiency,” the report found.

Mortality big factor

“Clearly, cattle mortality has been, and continues to be the most important limitation to beef production in Australia. The scale of annual mortalities, especially in female cattle, corroborates a separate, though similar analysis which also indicated annual mortalities of one million post-weaning-age cattle in Australia.

Although mortalities appeared excessive across the nation, the report authors (and others) had indicated that the primary contributor to the problem was mortalities of female cattle in northern Australia.

“If prevailing losses of post-weaning-age beef cattle and in excess of half a million calves annually can be halved, production may increase by more than 200,000t, which at 2021 cattle values equates to an extra half a billion farm income nationally. Strategies to further reduce mortalities of calves are likely to also reduce mortalities in older cattle, and vice versa, as they are inextricably linked.”

Emissions assessments

In addition to extra production, reducing mortalities would create substantial benefits in herd efficiencies and greenhouse gas emissions, through reduced loss of liveweight whose production has also incurred emissions, the report said.

Estimates of GHG emissions may need revision in view of the report’s findings that the national beef herd may be 40pc larger than previously estimated.

“These benefits will be further improved by development and implementation of management, nutrition and genetics that enable more efficient conversion of available feed to live weight, therefore higher liveweight production ratio (for example, females that can conceive more readily and are less prone to large annual fluctuations in live weight and body condition).

“It is interesting to speculate about what has driven the changes over the past 50 years in the Australian cattle industry, as this may affect structure and application of industry support services,” the report concluded.

“For example, increases in cattle growth and mature weights are likely to be primarily a function of genetics and feedlots. Large reductions in mortalities and improved beef cattle reproduction may primarily be a function of improved management and nutrition – for example, infrastructure development including secure fences and waters, better weaning practices, improved disease control, better transport systems, and ever-improving access to supplementary feeds that are being applied in a more targeted manner.”

“The long-term relative stability of the herd size and live weight suggests there has been no major long-term change to the feed base. Even if the opportunity is low to cost-effectively increase the feed base, strategies that preserve cost-effective feed production are vital in sustaining national cattle live weight production.”

MLA confident in existing herd data

Beef Central asked MLA for a response on the research findings, and a summary of current methodology used in industry herd assessment.

“This is an interesting piece of research and it will certainly contribute to industry discussions around the size of Australia’s cattle herd, which have traditionally suggested variances both up and down,” MLA said.

“Although we have not been involved in the development of this paper, we will closely review the findings. While MLA consistently reviews our industry projections model to ensure it remains accurate based on the available information, and to see if and where improvements can be made, we remain confident in the information we publish based on the variety of data that is used and wide range of consultation that occurs.”

MLA’s own herd size assessments published in its annual industry projections relies on a model using a number of data inputs, including ABS slaughter, herd and production figures, DAWE export data, NLRS data, BOM data, ALFA surveys and farm performance information.

Each year MLA undertakes a consultation process to verify its Cattle Projections numbers with industry, including engagement with large commercial cattle operators.

The model identifies key trends and relationships from history and applies those trends to the predicted seasonal conditions.

MLA made the point that the ABS’s national herd data was just one of many inputs used in the Projections model. The ABS data is used to reference the base herd number, however other data sources are used to determine and forecast the direction of the herd and the relative change in herd size.

Over the past five years, MLA forecasts of production and slaughter had averaged an accuracy of 3pc and 2pc respectively. These results are verified at year end against actual production data.

ABS’s herd size data is collected based on a survey – similar to what it does across a range of other published datasets, including the official census conducted last week.

Other findings, and questions raised

Some of the other key findings from the study:

- The beef industry has made incredible achievements over the past 35 years, increasing production by 80pc through improving cattle survival, reproductive output, and growth

- There remains room for considerable improvement in cattle survival, reproductive output, and growth

- The feed base for the Australian herd that underpins performance and production does not appear to change significantly, and reducing risks to it are vital.

Some key questions arising from the findings of the study include:

- What is the best balance between practices that sustain healthy pasture production in native and improved grasslands and feed production using sown pastures and crops?

- Are there too many cattle in Australia for the feed we have? Industry is using every strategy at their disposal to maximise utilisation of pasture available. Across the country there are bare paddocks, sometimes for years on end, and this has negative consequences for sustainability of pasture production, and therefore live weight production of the national herd.

- What can be done to reduce the incidence of mortalities of all animal classes in husbanded cattle herds?

- Are there implications for GHGE and carbon management strategies?