Simon Quilty

Independent meat and livestock analyst Simon Quilty provides his summary of the current state of play in the once-in-a-century drought, and what lies ahead for cattle supply, herd size, beef exports and processor viability…

THE Australian beef industry is killing its future, as we speak. The high liquidation of females and the increased production due to lack of feed and water is making life impossible for many farmers.

And for many beef processors, when rain comes it will make life impossible for them as well. In reality there are no winners in the long-term with a drought as severe as this.

The uniqueness of this drought has been the record temperature months in April last year, and December and January this year which has ‘cooked’ the pastures and robbed animals of stock water in many regions’ as described to me a by a feed expert.

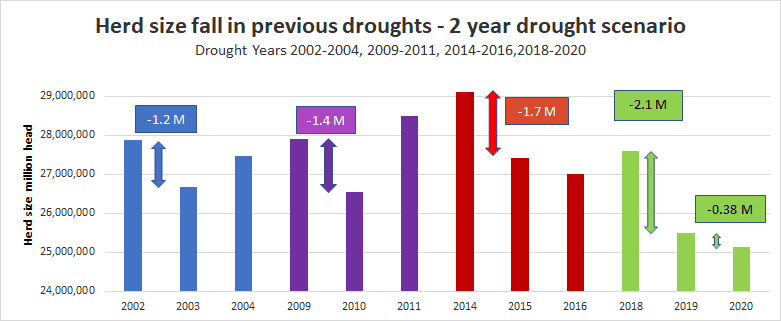

As a result we have seen an exodus of cattle from the system which I believe will ultimately see an Australian herd of close to 25.5 million head by the end of 2019.

The sobering fact is that without cattle, abattoirs run at much lower processing throughput for extended periods or there are plant closures (or a combination of both).

The lethal combination of low throughput and high cattle prices following a drought-breaking event can lead to a difficult processing environment.

The summary below looks at the consequences of ‘no feed, no water’ for Australia on the female kill and the size of the national beef herd; beef exports; cattle prices and potential plant closures.

The summary below looks at the consequences of ‘no feed, no water’ for Australia on the female kill and the size of the national beef herd; beef exports; cattle prices and potential plant closures.

There are few winners and losers in a drought like this. Farmers today are suffering and when rain eventually comes it will be processors who will be the next to feel the pinch due to lack of livestock and throughput. It’s an unenviable situation.

Any contraction in processing capacity for the farming sector means less competition for their livestock in the long-term. I truly hope it does not come to this, but I think it’s inevitable.

Australia’s herd liquidation continues

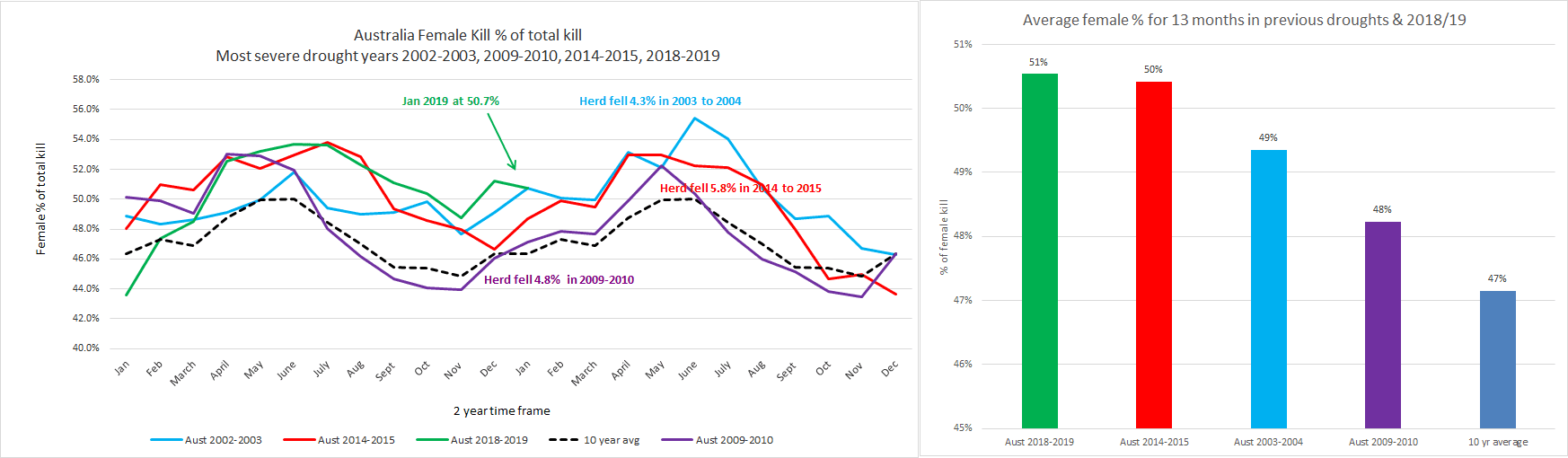

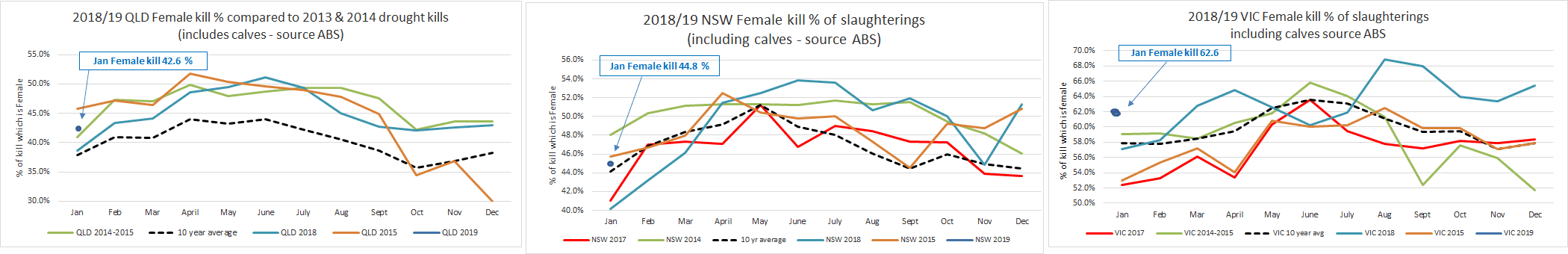

The January ABS kill figures were released on Friday, highlighting the ongoing liquidation of the Australian herd. The female kill was at 50.7pc, which is well above the ten-year average of 47pc and reconfirms that Australia’s breeding herd continues to be decimated as the drought continues to have a major impact.

This to me places this current drought as the most severe we have experienced in recent history.

Significant herd size fall expected

When assessing the impact of the last 13 months compared to previous droughts, the average female kill since 2018 was at 51pc, which is higher than the female kill ratio of the last three previous droughts for the same 13-month window.

In 2014/15, the female kill ratio was at 50pc at this stage in the drought, which saw the herd fall 5.8pc that year. It would not be unfair to assume that Australia’s herd size estimated in June 2018 at 27.6 million head is likely to fall by at least 6pc by June 2019, to 25.94 million head.

When flood losses of at least 350,000 head (some suggest 500,000 head) in northern Australia last month are added, this puts the herd at 25.5m head – a 25-year low in herd size.

Large cattle kills lead to larger beef shipments

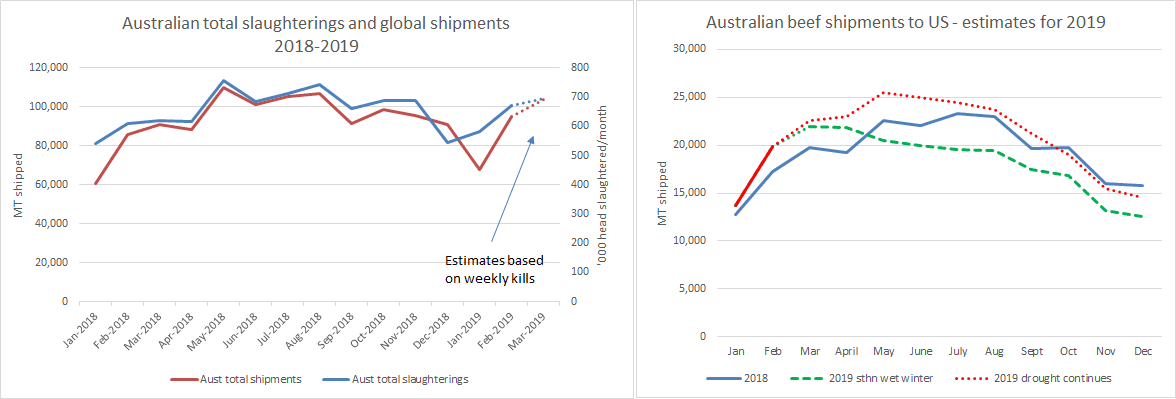

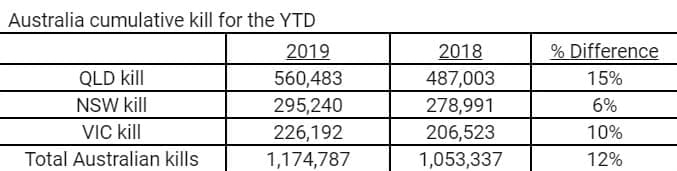

Weekly kills for Australia continue to be high, with Australian weekly slaughter rates year-to-date up 12pc on last year. Queensland leads the field with kills 15pc higher, with Victorian kills up 10pc followed by NSW kills up 6pc.

This is being reflected in larger beef shipments globally with March total exports likely to exceed 100,000 tonnes. This is the first time in six months that global shipments have passed the 100,000t milestone, signifying the drought has moved up a gear in the last five weeks.

US shipments:

Below I have outlined two scenarios as to what these kills might mean in terms of Australia’s 2019 beef shipments to the US. The first scenario is an ongoing drought, and the second, a traditional wet Australian southern winter.

In short, scenario one (continued drought) could see a 7pc increase in US and global shipments with most of this volume shipped in the first and second quarters. Under scenario two (southern wet winter) Australia’s global and US shipments could fall by almost 20pc compared to last year. This is under the premise that a depleted herd of close to 25.5 million head cannot sustain the current kill, even with the dry.

The clear message is that once upon a time, during drought, US shipments would have been 40pc of Australian global exports, and today it is barely at 23pc. This trend is unlikely to change with China and other Asian countries taking lean meat and providing healthy competition to the US market.

Weather update – looking at previous extreme dry weather trends

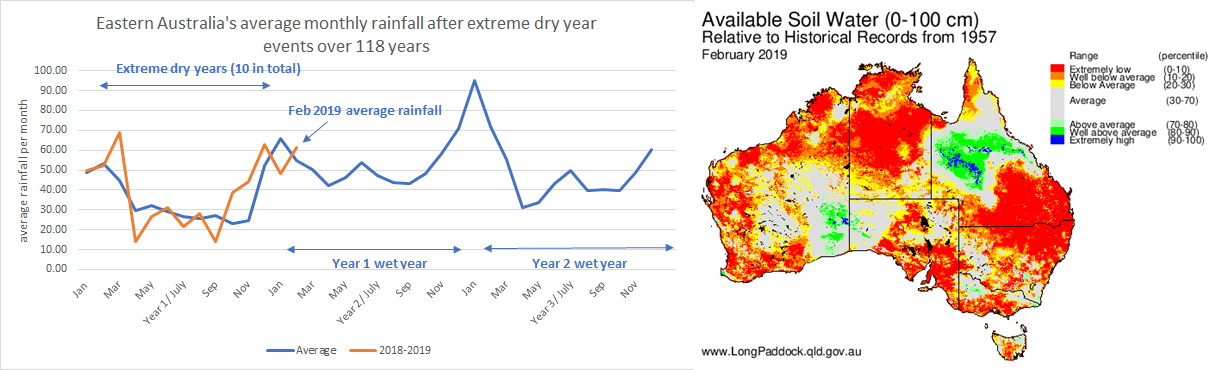

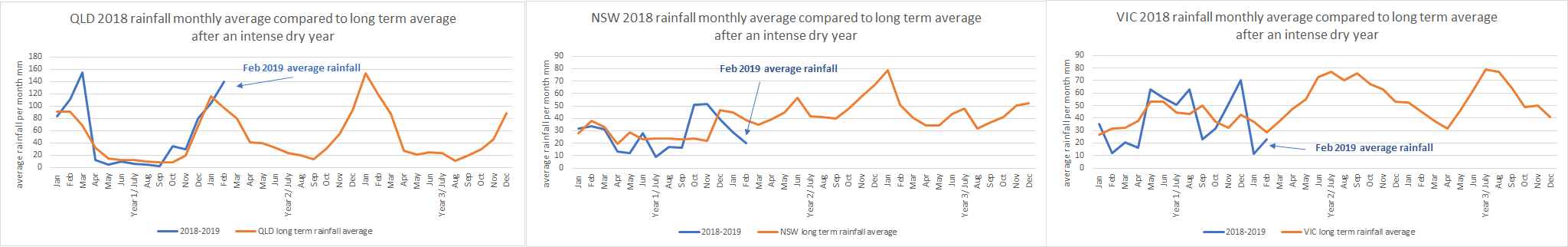

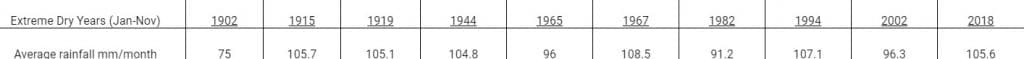

The following were the past extreme dry years that were similar to 2018 – these are the driest average rainfall years in Australia’s recorded history for QLD, NSW and VIC. I looked at what happened after each of these previous extreme dry years and in each instance the rainfall was higher in year two and three, and as stated 2018/19 is showing a similar trend for the last 13 months.

BOM’s outlook for Australia’s autumn is for a drier than average QLD, NSW, VIC and northern and eastern Tasmania, with two thirds of NT and eastern SA. The bureau predicts that inland western WA will be wetter than average. In addition, BOM has predicted that parts of northern QLD have a greater than 80pc chance of drier than average month for March with parts of the Pilbara and Gascyne in WA to be wetter than normal.

Peter Nelson, ex CSIRO meteorologist (based in Victoria and retired) had originally forecast a wet 2019 for outback QLD, NSW, VIC and TAS. His views have changed in recent weeks whereby the lack of breakdown in the dry conditions of inland QLD and north west plains of NSW and the extreme hot temperatures has him believing that there will not be any decent rain in central QLD until August this year, citing 1966 as important reference year.

He is now of the opinion that southern Australia will get a wetter than average winter with April being particularly wet, similar to key reference years of 1934, 1983 and 1940.

Peter Nelson’s views, to me, are falling in line with the long term trends after extreme dry years. Below I have outlined individual states and how February rainfall in each state is comparing to historic trends. Should these remain true, then Victoria/southern NSW will be the first to receive a significant wet event. Given these different views, it continues to highlight to me the ongoing need for independent views on the weather outlook from professionals.

Cattle prices are crashing – ‘no feed, no water’

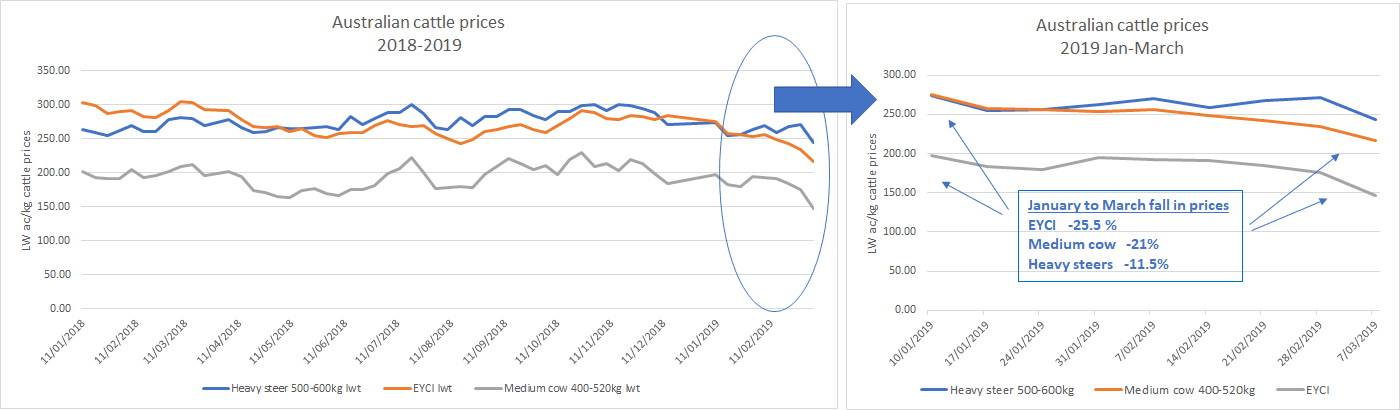

The recent flood of cattle into saleyards and the sharp decline in cattle prices in the last five weeks is a real concern. This is most notable by the EYCI falling 25pc since the start of January. This sharp decline is being driven by dry conditions, feedlots at full capacity and high grain/fodder prices.

There is little to no excess feed in the system. There is no doubt light feeder steers are problematic (a big part of the EYCI) due to reasons highlighted before – namely, the high cost of feed to make them market ready, a low priority in the feedlot sector due to Wagyu and longfeed programs taking priority, and the need for farmers to rid lighter steers in preference for their breeding herd as conditions get harder. In short, the market is still rewarding heavier cattle (grain or grassfed) and penalising light feeder steers.

A big part of the reason, I believe, for these recent dramatic falls in cattle prices is the record December/January temperatures which have severely impacted cattle and pastures. But there is now also a severe lack of stockwater that has become the big driver in selling livestock in certain regions and has led to a second wave of selling in recent weeks.

As one farmer said to me: “I have no feed, no water what else I am to do?” As a Victorian feed expert said to me: “Pastures are cooked – there is no moisture profile and it will take more than an average autumn break for pastures to rectify themselves. This is particularly so for northern Victoria and southern NSW. Annual pastures will not be put in until they see some sign of rain, so the lack of stockwater has added another layer of complexity.”

This to me sums up the situation almost everywhere on the Australian eastern seaboard whereby many regions which lacked feed but had stock water prior to Christmas are now lacking both with these extreme record hot temperatures effectively robbing these regions of surface water and what little pasture there was – hence the large yardings of cattle across Australia in the last five weeks.

Potential beef plant closures

The consequences of a low Australian cattle herd of 25.5 million, as forecast above, is that slaughter levels will also be very low.

In 2018, the yearly kill for Australia was 7.8 million head, from an estimated herd size of 27.6m head. Should the drought break this year, then I have estimated that the following two years would see the Australian kill fall to 6.4m head each year – in other words, 18pc less cattle throughput or the removal of 27,000 head per week compared to 2018 levels.

To put this in perspective, this equates to Victoria’s entire weekly cattle kill disappearing.

If the drought doesn’t break this year and high kills remain, it makes the eventual reduction in kill even greater, once a significant rain event does occur, due to an even smaller herd size. The longer the drought goes on, it is simply delaying and increasing the size of the problem of no cattle that lies ahead.

Which plants will shut, which will remain open?

The degree of liquidation across all Australian states and regions has varied, and I am not willing to say which state is going to be most adversely affected, and which plants would stay open or close.

However the general consensus among meat processors I spoke to was that several plant closures are more likely, rather than an industry-wide lowering of throughput shared by all. In other words, two to three years of processing over-capacity is likely, and short to medium term rationalisation seems inevitable.

When looking at each state’s herd liquidation (see below) it has been significant across QLD, NSW and VIC during 2018/19, with no particular state a standout. It should be noted that VIC’s kill reflects also the liquidation of the dairy and beef herd. So should closures occur, it will be based on many factors such as the severity of that region’s cattle liquidation, their role in export and domestic supply, live export influences, cost of inputs etc, and ultimately the bottom line of whether they can ‘make a dollar’.

In previous periods of extreme tight cattle supply, the decision to close often happens after a period of falling cattle throughput, with eventually the marketplace determining what is sustainable and what isn’t. This could take 3-18 months to determine.

Historically, droughts break in different regions at different times, so there are no hard-and-fast rules on how this might unfold. It seems to me that it will come down to a plant-by-plant assessment by each owner.

As stated I hope it never comes to this, but with a potential 18pc reduction in slaughter cattle throughput across Australia over a minimum of two years, and a likely yearly kill level of only 6.4 million head, something will have to give.