The best that can be said about the global economic outlook presented by respected economist James Shugg at a Rockhampton conference this week is that Australia is likely to be less afflicted by current problems than almost every other developed country in the world.

The best that can be said about the global economic outlook presented by respected economist James Shugg at a Rockhampton conference this week is that Australia is likely to be less afflicted by current problems than almost every other developed country in the world.

Westpac’s senior economist based in London presented a fairly daunting – at times outright alarming – view of the world’s economic situation heading into 2012, driven largely by the chronic financial and lending problems being experienced in Europe.

Mr Shugg was speaking to an audience of primary producer clients at Westpac’s Agribusiness Knowhow forum in Rockhampton. The event was the first of a series of such gatherings which will unfold across Australia in coming months.

He pulled no punches in warning the audience that there were some disturbing signs on the horizon which, if they unfold badly, could put enormous stress on the world economy.

Mr Shugg said he was more concerned currently about Europe and particular, and the global economy in generally, than at any other time in his 25-year career as an economist.

“Markets around the world are freezing up, banks are losing access to credit, and whatever people are reading in the current gloomy headlines, things are even worse than that,” he said.

“It’s a global catastrophe, frankly, and there is certainly going to be various impacts felt here in Australia,” he said.

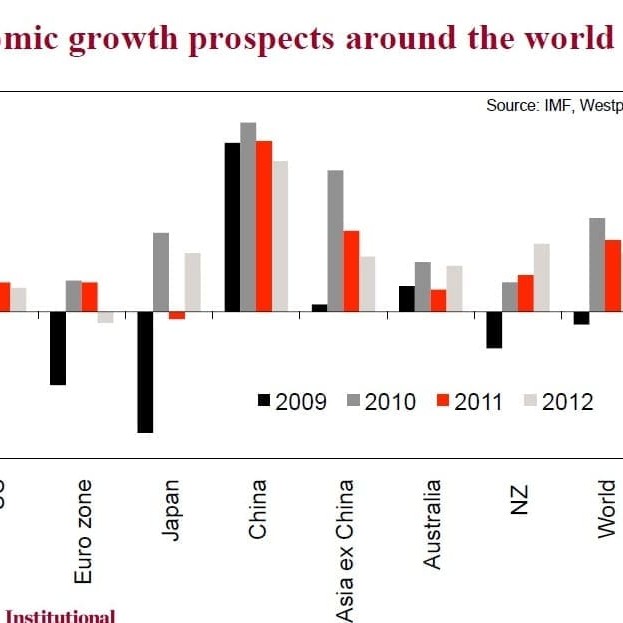

As the accompanying graph shows, the only economies in the world forecast to record economic growth next year compared with 2011 were Australia, NZ and Japan.

“The one thing those three have in common is recent natural disasters,” Mr Shugg said.

“The one thing those three have in common is recent natural disasters,” Mr Shugg said.

In Japan, the Tsunami hit economic activity very hard, but while it is starting to rebuild now and should record some growth numbers in 2012, Westpac is predicting Japan will hit a brick-wall in 2013.

In Australia, the flooding and cyclone hit coal and agricultural exports, but next year’s growth figures would reflect a recovery to higher production.

“But for all other major economies, next year will be weaker than 2011, and across Europe, a small recession is forecast of -0.6 percent,” Mr Shugg said.

European banks were pulling their borrowings out of other parts of the world, trying to get them back home to shore-up their domestic balance sheets. That, in turn, was having an impact in places like Australia and the US.

“In the US, we think the current numbers are over-stating the growth rate that the Government is claiming. As more accurate figures are produced, we think they will reveal that the US, also, is pretty close to recession again right now,” he said.

In China, the slowdown was engineered by the authorities, who were particularly worried about inflation and pressures in the property market. However evidence was coming through that the Chinese economy was slowing more than was anticipated.

Up until 2007, the Chinese economy was growing at 12-13pc. This year, the forecast is 8.3pc, and might move lower. If China was nudged down, the slowdown in other parts of Asia would be deeper as well, Mr Shugg said.

Westpac’s global growth forecast for 2012 was 3.2pc, but this could reduce to 2.5pc if these revisions were factored in.

“Given that the world economy grew at 5pc in 2010, the first year of economic recovery, the fact that that growth is likely to halve two years later is really abnormal,” he said. “Usually we see a much longer period of recovery after a severe downturn like we saw in 2009.”

There were lots of reasons for that, but the central one was that it was a banking-driven economic problem, which could take a long time to resolve.

Mr Shugg said the big global issue that economists were worried about was government debt levels.

While the start came with the sub-prime mortgage problems in the US, the actual value of those – ‘a hundred billion dollars or so’ – was only equivalent to one bad day on the stock market.

“But the huge impact it had on the rest of the world shows just how inter-related banking is with governments and other banks around the world,” Mr Shugg said.

“We saw contagion from the US sub-prime mortgage mess, into other parts of the world, and what’s happened now is that as mortgage debt became toxic, so too, did bank and government debt in some parts of the world.”

“There has been a re-pricing of risk in the past few years,” he said.

Loans were given at far too low interest rates in the first part of the last decade, and that risk was now being re-priced. Possibly it was over-shooting to the upside, but it meant that people or institutions that had debt were now having so much more difficulty in servicing it than what they anticipated when the debt was taken out.

That was particularly so in Europe, where the level of indebtedness had proven to be unsustainable.

In the case of Greece, an American investment bank last decade advised them on how they could fiddle their budget numbers so they could push payments into the future and hold down their budget deficit, so they could qualify to enter into the Euro.

“But unfortunately for Greece, the future is now, and that began the current intense focus on European government budget positions which has seen Greece lose its access to financial markets,” Mr Shugg said.

“If a government issues a 100 Euro bond, it might typically pay 5pc interest on that over ten years. But if lenders lose confidence in that government’s ability to repay or service the debt, in the secondary market it trades at a discount: it might only be worth 80-90 Euros. In Greece’s case, bond yields rose to 7pc, and given its economy was in recession at the time and the level of debt it carried, markets eventually decided it could not repay the debt and the rest of the EU and the IMF stepped in to provide a bail-out.”

The attached austerity measure conditions in fact put more downwards pressure on the Greek economy.

Along the way, Ireland and Portugal also lost access to financial markets through hugely over-leveraged banks. While these were smaller European economies, there were now increasing concerns over much larger Euro economies like Spain and Italy, where funding costs were also soaring.

The processes that these countries needed to go through to make themselves more competitive again, so they could grow at a faster pace and generate the tax revenues needed to service their debt, was an ‘awesome task,’ Mr Shugg said.

“And they are going to have to do it at a time that Europe is going into recession, and austerity measures are being put in place.”

In the next year, Italy had to either pay back or roll-over about 300 billion Euros, held in bonds. Spain was in a similar position.

“That is hugely concerning. If Italy or Spain lose access to bond markets because they can’t afford to pay to roll over their huge debt, they are too big to bail-out. The risk is a total collapse of European financial markets. It is a serious, significant risk,” he said.

The worst case scenario was that countries might leave the Euro, which would be catastrophic, but was now being considered as conceivable. If the Euro was to survive, it would require more fiscal union within Europe, where the better economies like Germany needed to put in place a system of transfers to the other economies.

Mr Shugg predicted that the current economic turmoil would be hugely disruptive to society, inevitably leading to riots and public unrest in some areas.

Within the banking sector, one of the flow-ons was that the credit market was freezing-up, just as it did in 2008, because everybody was ‘suspicious’ of everybody else. That trend had even hit Australian banks, to some extent.

The fact that European banks had their current problems was also pushing up the cost of doing business globally.

Other regions:

Looking at other parts of the world, Mr Shugg said there had never been an economic recovery in the US where housing prices had not participated.

Since the current recovery in the US began, housing prices had gone backwards by 25pc, meaning the spending related to housing was not occurring, and was holding down the economy. The US had had zero interest rates since 2009 and yet could barely grow, and more accurate data was likely to show the official data was over-stating the true economic story in the US.

Unemployment remained around 9pc, as it had been for a couple of years – and spending would not pick up while that was the case.

In China, all sorts of investment indicators were slowing down, which inevitably involved steel, iron ore and coal, sourced from Australia and Brazil. Iron ore prices fell 40pc in the past month, as a reflection of this.

Japan’s economy compared with the start of the decade, was showing very low levels of construction and other activity, and was going backwards. Adding to this was the aging population demographic and other issues, and consumers were saving, rather than spending.

The Yen was also becoming less competitive, because the Japanese currency was seen as a ‘safe-haven’ by investors.

The country also faced huge power shortages, with just 11 of 53 nuclear power stations still operating, post Tsunami, which would weigh-down very heavily on Japan once the recovery phase passed through.

Some concern over the health of Japanese banks might also come into focus, as it had in Europe.

Australia better positioned

Despite the doom and gloom across Europe, North America and Japan, the economic story in Australia was nowhere near as bad, Mr Shugg said.

“Nevertheless, there are reasons to be concerned. But as predicted by Westpac, inflation is falling in Australia and that’s why the Reserve Bank cut interest rates, as well as growing concerns over international outlook.”

Westpac’s official view was that there would be at least three more rate cuts ahead, totalling 75 basis points, and they might come more quickly than expected. While Westpac’s official view on currency was a bottom value around US 93c, under some scenarios it could fall back into the 70s.

Mr Shugg said what was different about Australia’s commodity boom now, compared with 2007, was that the ‘boom’ this time was not being spent. Businesses four years ago were investing across the board, hiring people, and unemployment fell to very low levels. House prices were rising rapidly and people were buying stuff to put into those houses.

Household savings rates in 2007 were zero, but were now 10pc, meaning people were now worried about rising interest rates and debt levels, preferring to save rather than spend. Outside of mining, businesses were actually cutting back on investment intentions next year, and the government had put in place the biggest fiscal tightening since the 1970s, despite Australia not having a Government debt problem. Every fiscal rating agency in the world now had Australia at AAA rating.

The problem was the Australian economy was heading downwards again, due to global growth concerns and slowdown in activity in China. There was also a lot of weakness in domestic parts of the Australian economy not exposed to mining. House prices had been falling for a year. Businesses were not borrowing money or investing.

“In a sense that is a good thing at the moment because it means our deposits are growing more quickly than our lending, meaning we do not have to access international credit markets,” Mr Shugg said.

But while there is no real chance of it actually happening, there has been a huge rise in the cost of insuring against default among one of Australia’s four big banks, because of what has been going on overseas. That was a proxy for the extra funding costs currently faced by Australian banks.

He said one piece of advice he could offer, given the parlous state of the global economy, was to watch debt levels, and “save a bit more.”

“Debt is still toxic, and even though Australia carries low Government debt compared with other countries, total debt is pretty high. Household and housing debt is very high, by world standards. As a proportion of income, Australians borrow more money for housing than America, Spain or the UK, where the housing markets have collapsed.”

“While this is not yet an issue for Australia, if the global economy became so weak that even the Chinese economy was hit hard, international investors would start to question the ability of Australia to service this level of debt. This is not a forecast, but it is still a low-risk probability,” Mr Shugg said.

His take-home message in the current environment was simple: “Live a little bit more within your means. If you are buying a new ute, go for the six rather than the V8. That’s the best way you can prepare for these sorts of circumstances.”