A monthly column written for Beef Central by US meat and livestock industry commentator, Steve Kay, publisher of US Cattle Buyers Weekly

A monthly column written for Beef Central by US meat and livestock industry commentator, Steve Kay, publisher of US Cattle Buyers Weekly

AS a long-time journalist, I am always fascinated by the beliefs that people strongly hold about a certain topic, whether the facts verify those beliefs or not.

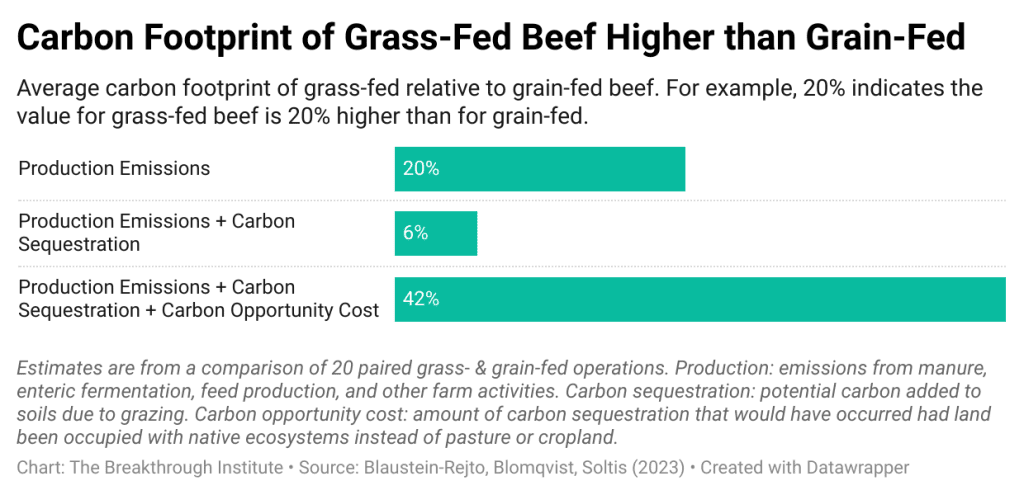

I recently came across a study that emphatically states that, contrary to conventional wisdom, pasture-finished operations (typically associated with a higher level of sustainability) produce 20 percent more carbon than cattle finished on grain.

The livestock industry’s previous notion surrounding grassfed cattle and their transition to grain-based diets before slaughter is now facing scrutiny after a ground-breaking study recently released by the Breakthrough Institute,* a California-based think tank.

The study conducted was an extensive examination of 100 beef operations from 16 countries, revealing insights that diverge from prior research.

Re-evaluation

The findings challenge the prevailing narrative that grassfed operations are inherently more environmentally friendly than grainfed. As environmental sustainability takes centre stage in global discussions about agriculture, the study prompts a re-evaluation of assumptions.

Diving deeper into the environmental impacts, when accounting for soil carbon sequestration and carbon opportunity cost, the total carbon footprint of these operations is a staggering 42pc higher, the study suggests.

This finding underscores the critical role of land use intensity in shaping the overall environmental impact of beef production. The implications extend beyond the immediate concerns of greenhouse gas emissions, emphasising the intricate relationship between land use practices and overall carbon footprint.

Beef sustainability remains topical

Meanwhile, beef sustainability continues to be a hot topic in the US, with consumers being the target of information campaigns from both sides, noted a recent article by Drovers.

News stories and social media posts abound with information about how much greenhouse gas emissions beef cattle produce and how much water it takes to produce a pound (or a kilogram) of beef. On the other side, beef advocates continue to promote the upcycling nature of beef production and the benefits of cattle on rangeland and ecosystem health.

The average US consumer does not have the knowledge and experience of the beef industry to sort these things out, says Drovers.

A recent US consumer survey funded by the Kansas Beef Council asked several questions about which beef attributes are most important, with particular focus on sustainability attributes, says Drovers.

Consumers were asked to rank the importance of attributes like flavour, nutrition, affordability, animal welfare, antibiotic and hormone use, locally produced, employee compensation, land and water conservation and greenhouse gas emissions.

Attributes ranked above average (greater than 0) by consumers from across the US were the traditional attributes of freshness, food safety, affordability and flavour. Among all the buzz about beef sustainability, these attributes are still the most important to the greatest proportion of consumers, says Drovers.

Among beef sustainability attributes, all were less important than the typical attributes of the beef eating experience, says Drovers. Of the sustainability attributes, animal welfare and no added hormones or antibiotics were ranked the most important.

One of the surprising results was the low importance of nutritional value of beef. Beef is a good source of vitamins and minerals and high quality protein. In fact, beef is nutrient-dense, meaning the nutrient (i.e. vitamin, mineral, protein) to calorie ratio is high. Probably the most surprising result of the survey was the low ranking of greenhouse gas emissions among priorities from beef, says Drovers.

US fed cattle prices impact from herd reduction

Regarding prospects this year for the US grainfed cattle market, cash prices will see a more modest year-on-year increase in 2024 compared to prior years. Prices are likely to average around US$183-184 per cwt live (basis a 5-area steer), versus an average of US$175 per cwt live in 2023.

Prices this year are likely to be up 5.4pc on last year. The 2023 price was 21.5pc higher than the average of US$144.41 per cwt in 2021. The biggest annual increase was in 2015 when prices advanced more than US$40 per cwt from the prior year.

According to analysts’ and USDA’s forecasts, prices are likely to range between US$172 per cwt and US$190 per cwt in the first three quarters. The fourth quarter will see the highest prices, in a range fromUS$183-203 per cwt live.

The higher prices, as they were in 2023, will be driven largely by five years of liquidation of the US cattle herd. January 1’s cattle inventory total will likely be down 2.5pc on last year.

The average annual forecast of US$183-184 per cwt live is far higher than the futures market is currently forecasting. January 4’s closes for 2024’s six monthly contracts saw prices average US $174.55 per cwt live.

US beef production in 2024 is likely to total 25.660 billion pounds, according to analysts’ average forecasts. That’s versus an estimated 27.118 billion pounds in 2023. USDA’s forecast is the highest at 25.990 billion pounds, while the lowest forecast, 25.3 billion pounds, comes from David Anderson at Texas A&M University.

The US feeder cattle and calf supply outside feedyards on January 1 was estimated to be down about one million head from the prior year, says Andrew Gottschalk of HedgersEdge.com.

On top of this reduction, the 2024 calf crop should score an annual decline of about 550,000 head. The supply side for feeder cattle and calves remains positive, as the available supply outside feedyards on January 1 projects to be at a record low.

Following a sharp fourth quarter sell-off, feeder cattle and calf prices are expected to rebound and score cyclical highs this year, he says. He expects prices for 750-800 pound (340-365kg) feeder cattle to average US $235 per cwt, versus US $218 per cwt last year. Calves in the 500-550 pound (230-250kg) range are estimated at US $296 per cwt, versus US $264 per cwt last year.

* Based in Oakland, California, the Breakthrough Institute is a global research center that identifies and promotes technological solutions to environmental and human development challenges. Its research focuses on identifying and promoting technological solutions to environmental and human development challenges in three areas: energy, conservation, and food and farming. Founded in 2007, the Institute’s early work built on the argument, first articulated in a 2004 essay “The Death of Environmentalism,” that 20th-century environmentalism cannot address complex, global, 21st-century environmental challenges like climate change. Because of the outsized impact that global food systems have on both conservation and climate challenges, in 2016 Breakthrough launched a food and farming program to offer new ways of thinking about agricultural innovation and policy. In particular, it made the case for industrial food systems. “Large-scale industrial food systems are more land, water, and GHG-efficient than small-scale low-intensity farming, and are better able to harness technology to increase land productivity, which holds the key to both climate mitigation and preserving biodiversity,” it argues.