ECOLOGICAL research is showing that historic populations of wild herbivores on the planet are likely to have been much higher than previous estimates have suggested, and were at levels that “more or less” match current domestic herbivore biomass across the world.

Pablo Manzano, a rangeland ecologist who works with the University of Basque in Spain and the University of Helsinki in Finland, says more evidence is emerging to show that previous studies have under-estimated the number of wild herbivores historically.

The research adds more scientific evidence to support the view that the planet’s populations of wild and domesticated herbivores have not increased their rate of emissions significantly over millennia.

Livestock grazing, given its similarities to natural herbivory, is a very important part of natural ecosystem processes, Dr Manzano told the Societal Role of Meat conference in Dublin.

Opponents of meat consumption and animal agriculture often portray livestock production as negative for the planet.

However, Dr Manzano said rangelands ecologists are helping to shift the narrative back to a more scientific and fact-based perspective, demonstrating the beneficial aspects of livestock production and the integral role herbivores have played in balanced ecosystems for millions of years.

“Very importantly the positive role of livestock has to do with being mobile and imitating the behaviour of wild herbivores,” Dr Manzano said.

“Wild herbivores and domestic herbivores can occupy the same ecological niche and it is positive that they are because they maintain a lot of fundamental ecological processes.”

Dr Manzano said the often-stated statistic that livestock are responsible for 14.5 percent of “anthropogenic” emissions does not take into account the natural baseline level of wild herbivore numbers.

He and his colleagues have examined the question of how many herbivores previously existed and how many there are now, with their fundings detailed in a paper published this month- see here: Underrated past herbivore densities could lead to misoriented sustainability policies

Dr Manzano said their research shows evidence that many areas of the world have historically carried natural densities of wild herbivores above 10 tonnes per square kilometre, “which is basically a lot”, Dr Manzano explained in Dublin.

“And which is much more than has been assumed previously by some studies,” he said.

“The evidence that has accumulated during the last 14 years shows that the potential number of wild herbivores is much higher than we thought.

“And interestingly it more or less matches the current domestic herbivore biomass in the world, which is a ray of hope, because it means that we potentially can feed the world through sustainable livestock keeping.”

Often-made claims that livestock contribute to anthropogenic climate change imply that all of the methane and nitrous oxide emitted by grazing livestock are a “net addition” to the amount of methane and nitrous oxide that in the system.

“And we know that this is not true because they occupy the niche of wild herbivores,” Dr Manzano said.

“So if we empty that niche and withdraw livestock from ecological niches, other herbivores – it can be wildebeest, it can be elephants, it can be deer, it can be termites – will move in, and will emit methane, and the quantity of methane they emit is not zero, and this is very important.

“Basically if you substitute domestic herbivores for wild herbivores and the herbivore guild is complete enough you are emitting the same methane and the same nitrous oxide per hectare.” This was also outlined in an earlier paper – Intensifying pastoralism may not reduce greenhouse gas emissions: Wildlife-dominated landscape scenarios as a baseline in life-cycle analysis.

Large wild herbivores have been a fundamental part of landscapes for at least 12 million years, and have shaped the ecosystems that we see today, Dr Manzano said.

If the herbivore guild is not complete, and no livestock is present, it will present other sorts of problems, he said, for example, more intense and destructive wildfires, as no one consumes much of the biomass in the landscape.

A ‘brown and black’ planet

While many think of the world as a “green” place, Dr Manzano highlighted the work of South African vegetation ecologist William Bond, whose research indicates the world is in fact a “brown and a black” place.

“Brown for the faeces of herbivores, black for the role of fire,” he said.

The natural state of large regions of Europe, the eastern United States or eastern China has not been closed forest for millions of years, as is often depicted.

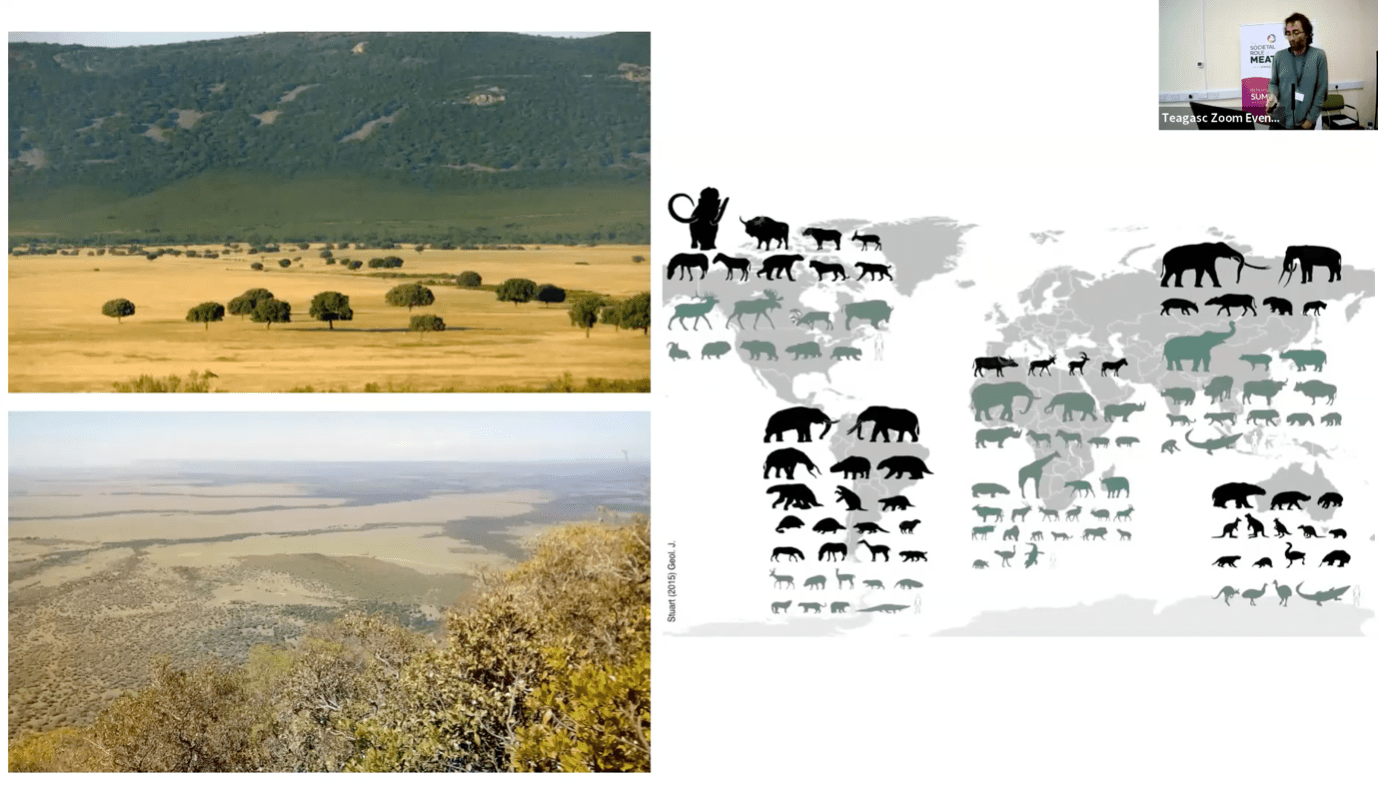

Rather, the evidence from vegetation ecology shows that these areas have been open landscapes, with populations of trees concentrated on the slopes and at the margins of these areas, and plains of mostly grass with scattered trees.

This is reinforced by images such as those at the top of this article of long-term protected natural landscapes such as the Cabaneros National Park in central Spain and the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya.

“Actually the name Mara in Swahilli means spotted because it is a grassland landscape with spots of trees in it,” Dr Manzano explained.

Livestock have enabled the structure of diverse ecosystems to be maintained

These complex landscapes have “a lot of trees, with a lot of shrubs and especially a lot of grass” and their ecological base relies on subtle equilibria between these three types of plants, which “interestingly causes sharp edges between these three ecosystems”.

“When you go to the verge of the rainforest in Uganda, I do field work in Uganda almost every year, and you see where the rainforest ends and the savannah starts, you see that it is a hard border, it is not gradual.

“And it is because of these relationships between the forest trees, the savannah trees, and the grasses and the competitions they are subjected to, the influences of fire, and also the influence of herbivores.”

Indigenous hunter gatherers used fire as a tool to keep landscapes open and populated by sun-loving grasses that need light to persist. This enabled them to have more prey to hunt and maintain supplies of meat, continued much later with pastoralism – “it was pretty much the same, although in a managed way”.

“And as a result, up until now we haven’t had great extinctions in small animals, in insects and in plants, because we have kept the same structure of ecosystems, and this is important because we have a lot of people saying that landscapes should be much more forested, and for most of the continental lands on earth this is not really true.

“We know also that for example for climate change it is really important to keep these open landscapes, because they are able to store a lot of carbon especially underground which is safer than above ground.” Carbon stored above ground was not as secure and could burn at any time, he said.

Dr Manzano stressed that there are better and there are worse ways of keeping livestock – “more destructive ways, and there are more beneficial ways”, the latter based on regenerative grazing techniques that imitate the behaviour of wild animals.

“When we analyse mobile pastoralism it is everywhere in the world,” he said.

“It is adapted both to the ecological circumstances and to the land tenure and social circumstances.. the thing is that moving livestock around is a trait that can be answered everywhere in the world because it makes a lot of sense.”

He said research of stationary farms versus farms where livestock are moved from one ground to another shows the latter is more productive and able to reduce the footprint per product compared to stationary farms where grazing stock do not move.

This was because animals lived in an “eternal spring”, eating high quality food, living longer and having more offspring.

To view Dr Manzano’s full presention click on the video below: