WHEN the Department of Agriculture called a halt to imports of pop star Katy Perry’s latest album this month, they weren’t making a musical judgement. They were protecting Australia’s biosecurity.

Biosecurity is also a process – a set of linked science-based protocols and procedures aimed at stopping unwanted pests and diseases from arriving in Australia, detecting and rapidly eradicating them if they do arrive, or (if they become established) trying to minimise their impact by using long-term management strategies.

Perry’s album included a paper impregnated with seeds so listeners could grow their own plants. While well-meaning, those seeds could pose a biosecurity risk. That’s exactly the kind of risk that gets investigated in efforts to keep pests out of our country.

“Biosecurity” was first used to describe preventive and quarantine measures to reduce the risk of invasive pests or diseases arriving at a specific location that could damage crops and livestock as well as the wider environment.

Today, biosecurity can encompass much more. It includes managing biological threats to our people, industries or environment. These may be from exotic (foreign) or endemic organisms but they can also extend to pandemic diseases and the threat of bioterrorism.

A challenging environment

Australia’s island status protects us from exotic pests and diseases to a certain extent, but we also have an enormous border to protect. International trade is increasing, and ships, planes and people are moving in increasing volumes across international and state borders. This means there is more pressure than ever on our biosecurity surveillance and response systems.

Australia has an enviable biosecurity and quarantine system. But there is no such thing as zero risk.

Invasive alien species remain one of the greatest threats to our biodiversity, and our agricultural productivity. The reality is that exotic organisms arrive in Australia regularly and sometimes become established. A critical element of biosecurity response is to prioritise which ones are of most concern and need rapid response.

Animal biosecurity

Protecting our livestock industries, native wildlife, human health and the environment from exotic or emerging pests and diseases of animals is the realm of animal biosecurity.

Australia is fortunate to be free of many highly infectious animal diseases, such as foot and mouth disease, highly pathogenic forms of avian influenza, African swine fever and many others that have serious consequences in other countries. An outbreak of any of these diseases could significantly impact the productivity of our livestock industries, and make it very difficult to trade our agricultural products overseas, as well as result in significant social and economic costs.

The 2007 equine influenza (horse flu) outbreak in Australia was a “wake up call” of how disruptive exotic disease outbreaks can be and why vigilant biosecurity is so necessary.

Avian influenza has recently been detected on poultry farms in NSW (fortunately not the strains that can affect humans). The widespread culling that followed shows how much social and economic impact individual farmers might suffer if there are future disease outbreaks. Strict farm level biosecurity is becoming increasingly the norm across many industries.

Plant biosecurity

Plant pests and diseases can significantly damage Australia’s productive plant industries. They reduce yields, lower the quality of food, increase production costs and make it difficult to sell our produce in international markets.

This is true across the massive expanses of our wheat production, and in the more intensive high-value production of horticulture, wine, cotton and sugar industries.

Plant pests and diseases may also be a huge threat to our natural environment: native forests, grasslands, and shrub lands.

Again, Australia is lucky to be free of many damaging pests prevalent elsewhere in the world. Citrus greening is a disease of citrus we definitely don’t want, whilst the varroa mite, for example, has devastated honeybee productivity and pollination success in every continent except Australia.

Fewer pest and disease problems mean lower production costs. Areas where rigorous biosecurity can deliver “pest freedom” gives Australian producers an enormous advantage in international markets and allows us to have safer and cheaper locally produced food.

Human biosecurity

Many emerging infectious diseases in livestock that also affect human health emerge from wild, native species. These so-called zoonotic diseases make up 70% of all the emerging diseases affecting human populations and include the likes of avian influenza, SARS and Hendra virus. The impacts of these diseases can be extremely severe and the need to manage livestock and human health risks in a unified way is also becoming much clearer.

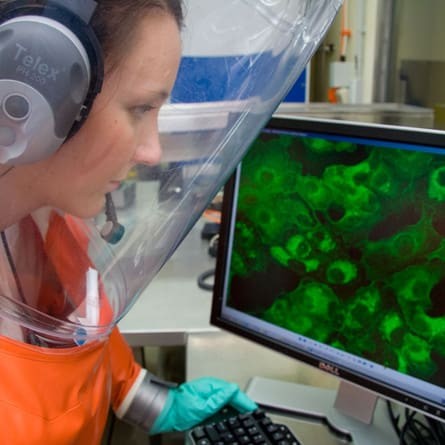

“One Health” is a new way of looking at the connections between the environment, production animals and emerging threats to people. As with animal, plant and marine biosecurity, human biosecurity is about effective surveillance and response, being aware of the risks that are circulating the globe, having the tools to rapidly detect and diagnose them and the tools and systems to respond quickly.

Working together

Biosecurity is both a process and an outcome. A successful biosecurity system requires scientists, government, industry, and the community to cooperate. In the end it is a system of shared responsibility.

Australia is achieving this by working together across the continuum. We investigate risks offshore, focus on surveillance and detection at the border, and research effective response and management systems within our borders.

Robust emergency response arrangements are in place to manage outbreaks. But preventing pest, disease and weed incursions in the first place, through effective and smart surveillance, remains a national priority.

* Dr Gary Fitt is Director of CSIRO’s Biosecurity Flagship and is focused on protecting Australia from the biosecurity threats and risks posed by serious exotic and endemic pests and diseases. Gary has spent much of his research career studying the Helicoverpa moth, an innocuous brownish moth, which is among the most damaging pests of Australian, and global, agriculture. His research on the performance and management of genetically modified Bt cotton varieties has provided the basis for current resistance management strategies in Australia.

* Dr Gary Fitt is Director of CSIRO’s Biosecurity Flagship and is focused on protecting Australia from the biosecurity threats and risks posed by serious exotic and endemic pests and diseases. Gary has spent much of his research career studying the Helicoverpa moth, an innocuous brownish moth, which is among the most damaging pests of Australian, and global, agriculture. His research on the performance and management of genetically modified Bt cotton varieties has provided the basis for current resistance management strategies in Australia.