AUSTRALIAN agricultural commodity export industries needed to be attuned to the changing operating environment in China, and the changing risk profile being faced over recent times – with a growing need to look at market diversification.

That was one of the key messages to emerge from a recent webinar convened by the Australian Centre for International Trade and Investment, titled ‘Australia-China Agriculture Trade: Challenges and Options’.

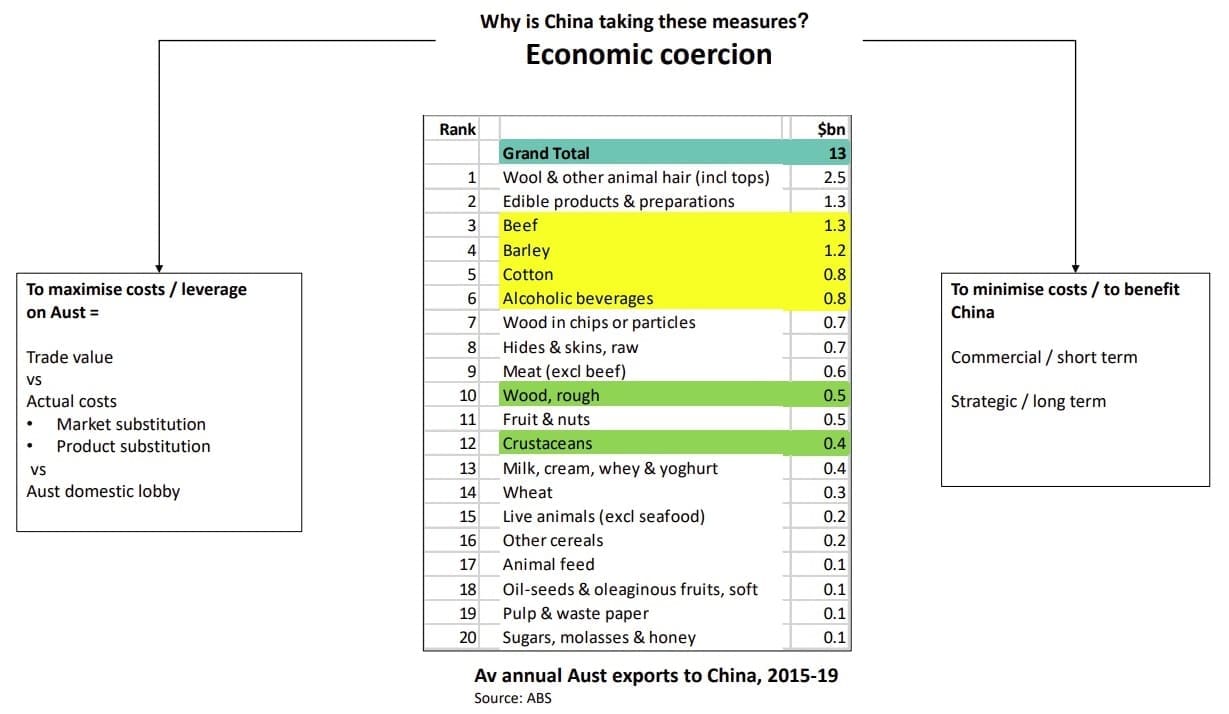

In setting the scene for the webinar, ACITI chief executive Pru Gordon itemised the long anf growing list of Australian ag exports that had been impacted by recent Chinese sanction measures including beef, barley, cotton, seafood, timber, sugar as well as coal and copper ore, and most recently, wine.

Ms Gordon said it was not particularly unusual for the Chinese to impose arbitrary trade barriers on exporters, or refuse to speak to Australian ministers or officials when Australia had ‘done something’ that had made them unhappy.

“But recent actions do appear to have been more targeted at penalising Australia, and it is also more difficult to see, at this point, how we might restore a more positive relationship with China, and therefore more certainty in our trade relationship,” she said.

Economic coersion

One of the webinar speakers attempting to provide answers over why China is taking the retaliatory measures it currently is with Australia was UQ academic Dr Scott Waldron, from the School of Agriculture and Food Science.

Along with Dr John Longworth, Dr Waldron was co-author of the definitive 2001 trade reference book, Beef in China: Agribusiness opportunities and Challenges. A well-thumbed copy of the book proudly sits on Beef Central’s reference library shelf.

Dr Waldron chose to use the term ‘economic coersion’ to try to explain some of China’s recent actions, and the specific targets it had selected in agriculture.

He said economic coersion was economic measures taken by one state that were designed to change the behaviour or policy of another.

“In this case, it is China trying to maximise the costs, and therefore the leverage on Australia to influence our policy, while also minimising the cost to China,” he said.

Dr Waldron said the starting point was the overall value of trade in different industries. As his table published here shows (compiled early last month), China had targeted four of the top six agricultural export items to China (highlighted in yellow), based on trade over the five year period ended 2019.

These are big industries with big trade value to Australia. But the trade value had to be balanced with actual costs, in terms of market substitution (i.e. if trade flow to China for a commodity is banned, it gets sold into another market), or product substitution (China bans barley, so Australian barley growers switch to wheat or another crop).

“But it depends on the industry,” Dr Waldron said. “In the case of barley, it was very exposed to China, but unlike a commodity like wine or cotton, through product substitution, barley growers could move to wheat, pulses or canola.”

In the case of wine or cotton, those big investments in infrastructure or machinery would increase the cost to those industries from China’s actions.

An earlier ABARES study suggested that while the barley trade to China was worth $1.2 billion annually, the actual cost to the industry through China’s actions was more like $330 million.

“In some commodities that have suffered total bans to China, the overall aggregate impact are not that high,” Dr Waldron said.

The way economic coersion worked, however, it was not so much about impacting overall aggregate flows, but to target particular exporting industries, where there could be a big impact on those industries. The theory was that those industries would then make representations to their government, attempting to influence government behaviour and policy setting, through those lobbying channels.

While the explanation above focuses on the cost side, the other part of the equation was the impact of trade limitations on China itself, Dr Waldron said.

Looking at the commodities listed on the table, the obvious question to be asked is, Why hasn’t China targeted Australian wool? It could be argued that to really do damage to Australia, China could target wool, worth $2.5 billion annually, and representing 80-90pc of all Australia’s wool exports.

“The obvious answer is that banning wool would in fact just do too much damage to China itself,” Dr Waldron said.

“Eighty to ninety percent of its fine wool requirements, for the worsted sector, comes from Australia, which would effectively close down those Chinese worsted mills if the trade was halted. China is not prepared to pay that cost, but it is for some of these other industries, where there are supply alternatives.”

Using Australian barley as a case study, Dr Waldron said Chinese domestic barley production had halved from four million to two million tonnes since 1992. Imports hovered around two million tonnes, before going ‘through the roof’ around 2015, because of China’s corn subsidy and substitution program that distorted trade.

As a result of these two things, total barley use then contravened China’s policy on food security – aiming to produce a substantial amount of important foods domestically.

Of the already high barley imports, Australia accounted for between 70 and 80pc, contravening Chinese policy settings on import diversification.

“China does not want to be exposed to any single source of imported commodities – especially from countries that China does not regard as being an ally,” Dr Waldron said.

“As a result, China imposed tariffs on Australian barley, using the argument that Australia was subsidising domestic barley production, and dumping it into the Chinese market below market prices, damaging China’s domestic barley production – and crucially, the incomes of smallholder Chinese barley producers.”

“We’ve been through the barley cases put by China character by character, stacked all the figures – and they don’t stack up,” Dr Waldron said. “It’s a spurious case, which China has since rejected.”

A similar pattern applied to wine, where China had ambitions to grow its own wine industry, but local production had declined. The China Alcohol and Drinks Association had claimed that the growing domestic market was being ‘robbed’ by imports, so it filed an investigation into wine dumping.

While beef into China was also a highly-managed trade, its circumstances were different. Technical barriers, labelling, residue and food safety issues added another layer of complexity to the trade’s recent challenges.

While most of China’s beef imports up to 2015 came through production smuggled in from neighbouring countries, Australia originally accounted for about 50pc of imports. But China has since been able to diversify imports from other areas, especially South America. By 2019, Australia accounted for just 16pc of imports.

“But that’s a good position to be in, compared with a lot of other commodities where China is much more reliant on a single supplier.”

Dr Waldron said there were some concerning signs emerging in China in terms of structural forces, such as agricultural subsidies at a time when the rest of the world was declining subsidies, ignoring rules-based trade with tariffs and other mechanisms, and the broader concerns (discussed above) through economic coercion.

So how can Australia respond?

“The really important thing in considering responses is to accurately value the real cost of these barriers,” Dr Waldron said.

“We don’t want to under-state the costs, but equally, we also don’t want to over-state costs, that might lead to other actions or behaviour that is unnecessary at this stage,” he said.

He said industry bodies like the red meat industry’s AMIC were not getting caught up in the ‘tit-for-tat politics’, but were working with government to put their heads down and work through the technical issues in front of them, and make cases to China.

“Importantly, businesses are now really starting to understand the risks of dealing with China, and just as part of normal business practise, to internalise those risks. With additional risks, there’s a lot of Australian beef plants looking at diversifying their markets,” he said.

“I recently went through submissions to a recent federal parliamentary inquiry into trade and investment diversification, and all but one submission from industry groups and individual ag companies were arguing for diversification.”

“But that doesn’t happen in a vacuum – it’s supported by a big apparatus of government departments, biosecurity specialists and countless others.

“That’s the question for Australian agriculture – how to deploy those resources to expand trade into markets other than China.”

Business-to business dialogue continues

Also speaking during the webinar was Australian Meat Industry Council chief executive Patrick Hutchinson, who said there had been a huge amount of media coverage recently with regard to Australia’s meat trade into China.

“The red meat industry has been somewhat different to many others up to this point in that recent issues have been on a business-to-business basis, as opposed to an overall industry impact.

“But we also know that it has been a targeted nature by which these individual businesses have been looked at.”

There were now eight Australian red meat processors that have been impacted – the original four which were temporarily suspended due to labelling issues; another more recent case that was temporarily suspended due to a claimed residue issue; two self-imposed Victorian suspensions back in July due to COVID sickness among staff; and Monday’s suspension of Meramist in Queensland.

“We had hoped the two self-imposed Victorian suspensions due to COVID issues would have been re-activated again fairly quickly, now that Victoria is COVID-free, but it is taking an inordinate amount of time,” Mr Hutchinson said.

Behind the scenes, what was not known was exactly why these actions from China had been taking place.

“What are we really looking at, in the reasons behind these suspensions?” Mr Hutchinson asked.

He pointed to an earlier article from the South China Morning Post, which talked about the Australian Anti-Dumping Commission assessing possible continuations of dumping duties on China, across a range of different products including aluminium extrusions, fly screens, TV aerials, stainless steel sinks and photo-copy paper. Such counter-measures rarely were discussed in local media reports, but there was always going to be a sense of retaliation backwards and forwards over such matters.

Asked what realistic action the Australian government and industry could take, Mr Hutchinson said a key focus was internal or domestic China relationships.

“Certainly for the meat industry, we have been to China a number of times, making strong investments in time and resources to meet with key stakeholders. We (Australia and China) currently do a lot of business-to-business and government-to-government relationship work, but we don’t do very much association-to-association work, between importers and exporters, looking at sharing common goals,” he said.

In September last year, AMIC signed an agreement with the China Meat Association, to work on how best to share intelligence, and manage and improve relationships, and how to get the most out of any MOU that gets signed.

“But as we all know, this year, 2020, has been difficult, across a number of areas.”

“We also need to learn, as an industry and as a country, that with this relationship with China, what’s most important is that outside the government to government freeze that’s being seen, we (industry members) can still keep talking.”

“It’s important from an industry to industry perspective, that we keep those strong relationships in place. We also know it does not pay us in any positive way, either here or in China, if we go out and start chastising our own government for its decision-making, without having a detailed understanding of what’s going on behind the scenes.”

But equally, trade could never be collateral damage in the dispute process.

“It’s about weighing up what the mechanisms are that allow us to check and manage those key areas.”

Mr Hutchinson said despite the recent trade disruptions, Australia still looked like having its second biggest year on record, by volume, for exports to China this year.

“For example, for the nine months to the end of September, chilled beef exports were only down 1pc on last year,” he said.

“It’s the frozen product that is down about 22pc over the same period. There’s a range of issues behind that, most notably to do with storage, because coming into Lunar New Year, there was a huge January and February in regard to exports, however with it being filled and then the first COVID lockdown after Lunar New Year, the Chinese people did not travel as they normally would, or consume the red meat products that they normally would, via food service.”

Mr Hutchinson said AMIC continued to work with its MOU partners – MLA had an office in China, and worked hand-in glove with the Australian Embassy with regard to delivery of information and sharing intelligence.

“However at the end of the day, with all of the work going on underneath, we still have this issue above and beyond between governments.”

“At this stage, Australia’s regulators are still struggling to get some traction in those areas, and we should never forget that Australia still has 15 facilities that have not got their China license at all – even though that was signed-off on three and a half years ago in the joint statement between Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and the Chinese Prime Minister.”

“We are still waiting for all Australian exporters to have chilled access, and we’re also waiting for the ability to export tripe, which is considered a delicacy in China, and which Australia has a great opportunity to provide.”

“But industry is certainly working behind the scenes, internally within China, with our MOU links, with our MLA links and with our business partner links in China – but if the government-to-government level is not working, then nothing will happen.

“So we need to continue to do our bit, in our areas, so that when the respective governments do start engaging again, that we are ready to go.”

A senior China market specialist with the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, who asked not to be identified for this report, spoke during the webinar, saying that while 2020 had been a tough year in so many ways due to COVID, China had been one of the first countries to bring the virus under control within its borders.

“China is now expected to be one of the few economies worldwide to have positive economic growth in 2020, perhaps reaching 2pc GDP growth,” he said.

“Australia has a good reputation in China as a reliable producer of clean and safe food, and Chinese consumers are clearly prepared to pay a premium for high quality, safe products.

Last year, China accounted for around one third of Australia’s agricultural exports, valued at around $16 billion – assisted by the China/Australia Free Trade Agreement, providing preferential or zero tariffs on most agricultural and food exports into China.

Ag exports into China had increased by 53pc since CHAFTA was struck in 2015.

“That’s good, but like elsewhere, agriculture in China has always been politically sensitive and highly regulated. In China those concerns are more acute, given their historic of problems with food safety. Chinese regulators and officials are very risk-averse, as a result – and this year, the COVID pandemic has added to an already complicated and sensitive regulatory environment.”

Since March, new requirements were added on food imports including border testing, import declarations, requests to audit food establishments and some suspensions of food establishments in different parts of the world which had COVID cases. All this impacted trade and market access, and in the case of the Australian meat industry, in two cases voluntarily suspended China exports from two red meat plants that had sustained COVID cases (see yesterday’s separate story), rather than have China impose its own suspensions.

“We’ve done the right thing in that respect, and are asking now that they do the right thing, and restore our access, now that those COVID sickness cases have been resolved,” the trade official said.

Perceived risks

Exporters, including those from Australia, had also had to deal with perceived risks within China about transmitting COVID via either frozen food or its packaging – even though there was no scientific evidence, to the Australian Government’s knowledge, that such transmission risk exists.

All frozen and chilled food exporters had had to be ‘more careful’, and over the past few months there had been a lot of testing of imported products and packaging in China. Some exporting countries, particularly in South America, had had problems as a result.

“We all know that the bilateral relationship with China is more strained these days, and that’s an added complication on top of COVID concerns.”

The background to this was that Australia had taken a number of decisions over the past few years on national security and related issues which China regarded as sensitive – such as Hong Kong developments and a call for an international review of the source of the COVID pandemic.

“China has objected to those positions, leading to the bilateral relationship coming under considerable strain, impacting the political dialogue at the ministerial level,” the trade representative said.

“We (the Australian Government) do not think this is a reasonable response by China, and we do not want our issues to dominate our bi-lateral relationship. Certainly there are issues that we do not agree on, but we don’t think those issues need to be front and centre. We think it is unreasonable that they impact on commercial activity, because those commercial relationships are to the benefit of both sides.”

Nevertheless, along with the more tense political atmosphere this year, trade between the two countries has encountered a number of impediments – principally red meat, barley, cotton, seafood, and more recently, wine and timber.

Through media channels, China recently warned that there would be ‘more bitter fruit’ for Australia to swallow if it continued its anti-China stance, and “continued to ride on the US bandwagon of strategic confrontation with China.”

“For the Government’s part, we are committed to dealing with each trade issue as it arises, on its merits – working closely with industry to address China’s questions and issues, and taking up concerns from our side with the Chinese authorities,” the diplomat said.

He said the Australian government also reserved the right to take further steps through the World Trade Organisation.

**However Australian export industries needed to be attuned to the changing operating environment in China, and the changing risk profile being faced over recent times.”

“It’s also important, of course that exporters are scrupulous over technical issues such as labelling. Like many other countries, China has very high standards in what it wants to import.”

Through ministers Birmingham (trade) and Littleproud (agriculture) the Australian government had made it clear to China that we are ready to discuss these issues, and the embassy is in contact on the ground with Chinese authorities on a daily basis to convey our concerns, and seeking explanations to resolve recent issues.

“China’s reputation as a trustworthy and reliable trading partner is at stake,” the trade representative said.

He said as opportunities arose, steps were being taken to pursue additional market access openings – particularly in view of the concessions China has granted to the US under the phase one trade agreement.

“But it’s a complicated picture, with plenty of work still to do,” he said.