THERE’S a growing belief around the industry that at some time in the next year or so, Australian feeder cattle could be exported live to the United States.

MV Ocean Drover

Australia has never previously exported cattle by sea to the US (* see reader comment at bottom of page) – but supply, demand and price cycles over the medium-term are making the prospect look more likely.

Beef Central was told that as recently as December, major US feedlot operators contacted the Australian live cattle export industry inquiring about prospects and feasibility for live feeder trade. It’s understood that interest was more about preparing for the future, rather than any direct interest in importing feeders at that particular time.

Three factors need to work in unison in order for Australian feeder cattle importation to look financially viable into the US market, Beef Central was told:

- US feeder cattle prices need to be relatively high

- Australian feeder cattle prices need to be relatively low, and

- The Australian currency needs to be low, relative to the US dollar.

US feeder prices have already lifted by around one third in value since this time last year (see reasons below), and are forecast to head much higher over the next 12 months as the impact of dramatic US herd decline takes full effect.

So how do the sums look?

Australian heavy flatback feeder cattle are this week making around 335c/kg liveweight, about 45c/kg lower than this time last year, and the Aussie dollar sits this week at just above US65c. That’s at the lower end of the long-term currency range – down US2.6c on this time a year ago. A year earlier in March, 2022, the A$ was trading above US75c.

In round terms, an Australian flatback feeder 400kg* is this week worth around A$1340. When converted into US$, that represents a value of US$885/head. (nb: US feeder cattle tend to be lighter than those in Australia).

Just back from a recent US marketplace visit is Stonex cattle swaps manager, Ripley Atkinson. He said similar US feeders are currently making the equivalent of A615c/kg liveweight. In local US currency terms, it means 400kg US flatback feeders are currently worth around US$1624, suggesting a current price differential of about US$739. (Editor’s note: Since this item was published yesterday, we’ve received further information suggesting US feeders today are quoted at US$2.47/lb (US$5.47/kg). Converted into Aussie currency, that represents a price of A$8.29/kg, liveweight).

But the key point is, US feeders are widely anticipated to get much more expensive, as the year progresses.

Mr Atkinson’s recent discussions with US industry contacts suggested there was wide expectation that local feeder prices will rise substantially, some time in the second half of this year.

“The impression I got was that they anticipate the next four or five months will be fine for feeder supply, but getting into northern hemisphere Fall (Australia’s Spring), that’s when US feeder supply is likely to start to unravel,” he said.

“While its all still in the ‘what if’ stage, if feeder trade was to take place into the US, it would add an extra level of competition for better feeders in Australia – between Australian lotfeeders themselves, and their US competitors,” Mr Atkinson said.

An experienced live export industry contact provided the approximate figures below, to illustrate what shipping costs to the US might look like:

- Shipping and all Australian-end preparation and protocol costs – A$1200 per head

- US end costs of arrival, quarantine, ESCAS etc – A$500 per head.

That suggests a feeder price differential of A$1700 per head would be needed to make the basic sums for trade stack up. Currently that figure stands at A$1120.

“It might not be a workable proposition at the moment, but once the US drought breaks and cattle supply gets short, the price of feeders in the US will go to the moon – as it does in Australia after a drought,” the live export contact said.

“So it would give the Aussie market a nice boost. The limiting factor of course is shipping, which is quite limited and the trip takes so long, so it probably means that the total upper limit potential numbers per year might be in the order of 100,000 head,” he suggested.

Drought’s major US herd impact

Two years of serious drought has had a deep impact on the US beef industry. The US beef herd last year fell to a 52-year low, at 29.4 million beef breeding cows, reflecting a fifth year of declining beef cow numbers.

Conversely, when Australian feeder cattle prices were pushing past 550c/kg and 600c/kg liveweight at different times in 2021 and 2022 following our own drought, there was some casual interest shown around the industry in the prospect of importing US feeder cattle into this country.

At the time US feeders were considerably cheaper than local Australian feeders, once currency was factored in. The prospect never made any progress, beyond the discussion stage, however.

Health protocols for live cattle to the US in place

Beef Central has been told a health protocol for live feeder cattle from Australia to the US is already in place, and can be used.

One trade source said there was a small challenge with Australian export yards needing to be double-fenced on the boundary and clear of vegetation as a condition to reduce the risk of ticks getting on cattle. All live cattle exported from Australia are free of ticks by way of region-of-origin or chemical treatment, but the US has this additional measure.

“I think the Australian export yards would build an external fence around their facilities, and some that already do breeder export cattle have these in place, for additional security,” the source said.

Some US importers have told the Australian live export industry that there may also be issues with the US Jones Act, which regulates which vessels (by country of ownership) can and cannot be used to service US shipping ports.

US already imports 2m cattle per year

The US is certainly no stranger to live feeder and slaughter cattle importation. The country is arguably the biggest importer of livestock in the world, with total cattle imports in 2023 falling just short of two million head.

That figure was up 22pc on the year before, representing an additional 352,500 head. The increase was due to greater numbers out of Mexico (up 43pc or 375,854 head) to more than 1.2m head. Cattle imports from Canada totalled 734,0000 head in 2023, down 3.1pc from 2022, due to declining Canadian herd size.

All of the US live cattle import trade last year was by road.

Would livex to the US compete with Australia’s existing markets?

One question that has arisen is whether any new live cattle export trade into the US would compete with Australia’s existing live export markets, principally Indonesia and Vietnam.

People Beef Central spoke to on this topic felt that the US would be looking for a completely different style of feeder animal – ideally, marbling-oriented Angus or Angus cross targeted at the grainfed USDA Choice or Prime beef grading categories – not the Brahman based animal on which the Asian livex trade is based.

That suggests likely loading ports like Portland in Victoria, or Brisbane in southern Queensland would be favoured.

Slowdown in US slaughter

US meat and livestock market analyst Len Steiner has written recently on the changing price and availability environment for US feedlot cattle, and meat protein in general.

He said US feeder cattle prices had now risen more than 30pc compared with March last year, mostly due to availability.

For the week ending March 2, US domestic beef producton was down 194 million pounds (‐4.2pc) from a year ago.

“There has been a consistent shortfall in red meat and poultry production in the first two months of the year, impacting both pricing in the spot market and the supply of product accumulated in cold storage,” Mr Steiner said.

The week before last, total US cattle slaughter was 599,000 head, down 4.2pc versus a year ago and down 9pc and 10pc respectively versus 2022 and 2021.

“That cattle slaughter numbers are down should not come as a surprise to anyone that has been paying attention,” he said. “But what may be surprising is that weekly fed cattle slaughter in the four complete February weeks averaged 2.2pc under last year – even as the supply of market-ready cattle on February 1 was 6pc higher than last year.”

“Packers are struggling with negative margins and reducing slaughter, while feedlots are struggling to find replacement stock,” he said.

“Going forward, supply will only get tighter. Lower feedlot placements in January were an indication of what’s to come. If the USDA cattle survey is right, there were 1 million fewer feeder cattle outside US feedlots as of January 1 than the year before (‐4.2pc). This will limit supply availability in late spring and summer,” he said.

Can history tell us anything about live export prospects to the US?

There is nothing new in the concept of selling Australian cattle live to the United States.

Back in 2001, feedlot industry stakeholders in the US were seriously eyeing-off the prospect of live cattle imports from Australia.

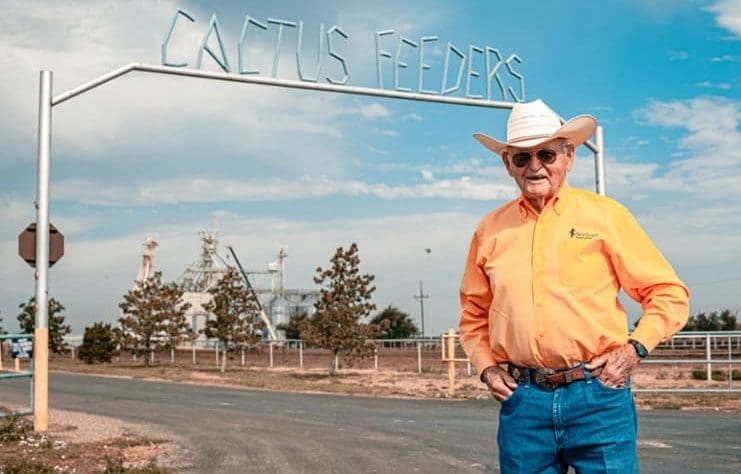

Paul Engler, the head of Cactus Feeders, the largest privately owned lotfeeder in the US, was in Australia to speak at the grainfed industry’s BeefEx conference. He dropped a bombshell when he said he was exploring prospects to import live Australian feeder cattle, saying he believed there was solid scope to develop a significant live export trade direct into the US.

It made compelling financial sense: at the time, the A$ was worth only around US52-55c – it’s lowest value since the Australian currency was floated in 1983. That would give any prospective US feeder steer buyer enormous buying power in Australia.

Additionally, the US cattle herd was surprisingly low, at around 97.3 million head – not that far above where it sits today. An MLA analyst told Beef Central that at the time, Aussie trade steers (mid-2001) averaged 185c/kg (liveweight), while the Chicago Mercantile Exchange feeder index in August 2001 was 375c/kg (liveweight) – twice the price. Both prices quoted are in Australian currency.

Paul Engler. Image: West Texas A&M University

It’s not hard to see why large US feeder cattle users like Paul Engler got excited.

He said at that time that Cactus had been working ‘behind the scenes’ on developing the trade for the previous six months. He had “always been convinced that Australia produced quality feeder cattle cheaper than anyone else,” and with advanced shipping operations, it was an ideal time to capitalise on the opportunity.

Cactus Feeders planned to import its first 5000 head by December that year (2001). Mr Engler said at the time he was waiting on the State-based Texas Animal Health Commission to provide details of specific risk assessment issues it wanted to follow through.

The shortage of good feeder cattle in the US was driving the interest in trying to import Australian cattle, Mr Engler said. In addition, he saw it as a way to support the concept of free trade.

“At the current exchange rate of US52c to the A$, even though Australian cattle are currently seeing record high prices, they still cost almost half what they do in the US,” he said at the time.

Based on the low price of feeder cattle in Australia, shipping expenses brought the total cost of importing the cattle to around US$70-75 per hundredweight, well below domestic prices at the time.

The story began six months earlier, when a shipping company approached Cactus representatives with the idea of exporting cattle from Australia to the US. The company had ships capable of transporting up to 20,000 cattle, and considerable experience shipping live cattle from Australia to the Middle East and Asia.

Cactus began exploring the possibility and made inquiries about what the USDA and the Australian government were doing to develop a protocol and approval process.

“Our attitude from the beginning was that if the imports were permitted and the economics worked out favourably, we would view Australia the same as other exporting countries. We also believed that the burden was on the Australians and the shipping company to secure the necessary permits from the US government,” Mr Engler said.

In July 2001, the shipping company asked Cactus representatives to sign an application to import 4800 head of cattle from Australia during January 2002.

“We signed the application with the understanding that they would not submit the request until after the US government had officially approved imports of Australian cattle,” Mr Engler said.

Proposal attracted vigorous criticism

Within days of making his comments in Australia, Mr Engler’s plans attracted vigorous criticism from US cattle lobby groups, ostensibly on animal health grounds, but widely interpreted in Australia as an intentional barrier to trade.

The US National Cattlemens Beef Association told US cattle market analyst Steve Kay – now a regular columnist for Beef Central – that while it was “obviously not thrilled” about the prospect of imports of feeder cattle from any new country, the association’s principal concern was that imports follow all health protocols and did not endanger the health of the US cattle herd.

Then NCBA chief executive Chuck Schroeder said beyond that, the US was a free country in terms of the commerce that companies entered into. Other US industry lobby groups like R-Calf also stridently opposed any opening of trade.

Importing Australian feeder cattle would obviously be a political issue in the US industry, Mr Engler conceded at the time.

“If I were a rancher in Montana, I would feel the same way some ranchers apparently do. But in a wider context, people have to look at what free trade is all about. What’s the difference between importing cattle from Mexico or Canada, or from Australia, provided any animal health issues are addressed?” he asked.

“If one considers globalisation and free trade, the US might import feeder cattle from many different sources in the future. The US imports more than 300,000 tonnes of beef from Australia each year, so why not import feeder cattle instead and add value to them in the US and generate revenue and jobs here?”

A phalanx of regulatory issues emerged that meant the proposal never got off the ground in 2001.

One was the use of private, versus limited government quarantine facilities. While Mr Engler said he was originally told that all of the protocols had been met and approved by the US government, USDA’s APHIS said that while import protocols had been drafted, final approval had never been granted.

“I think producers in the US are flabbergasted that it would be cost-effective to ship these animals 10,000 miles across the ocean. That they’re even contemplating it is amazing,” NCBA’s Chandler Keys said at the time. He said NCBA, like all of the parties involved, saw animal health is its top concern.

“We would hope the Australians would, too. These animals have never been exposed to any of our respiratory diseases, either,” he pointed out. “Those things need to be looked at.”

Some of the strongest objections come from Texas and Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association, which urged the USDA to use extreme caution when considering any request to import commercial feeder cattle from Australia. A major concern was the health and quarantine protocols that would be used.

“Obviously, there are diseases common to Australia which do not exist in the US. It is our understanding that an intermediate destination of such a shipment would be the Gulf coast of Texas, and that these cattle would be quarantined, transported, fed and processed in the state. Consequently, a vast quantity of the state’s 14 million head of cattle could potentially be exposed to diseases or vectors that do not exist in Texas, if the appropriate quarantine procedures are not implemented and strictly enforced.”

Exactly what the “diseases common to Australia” were was never explained.