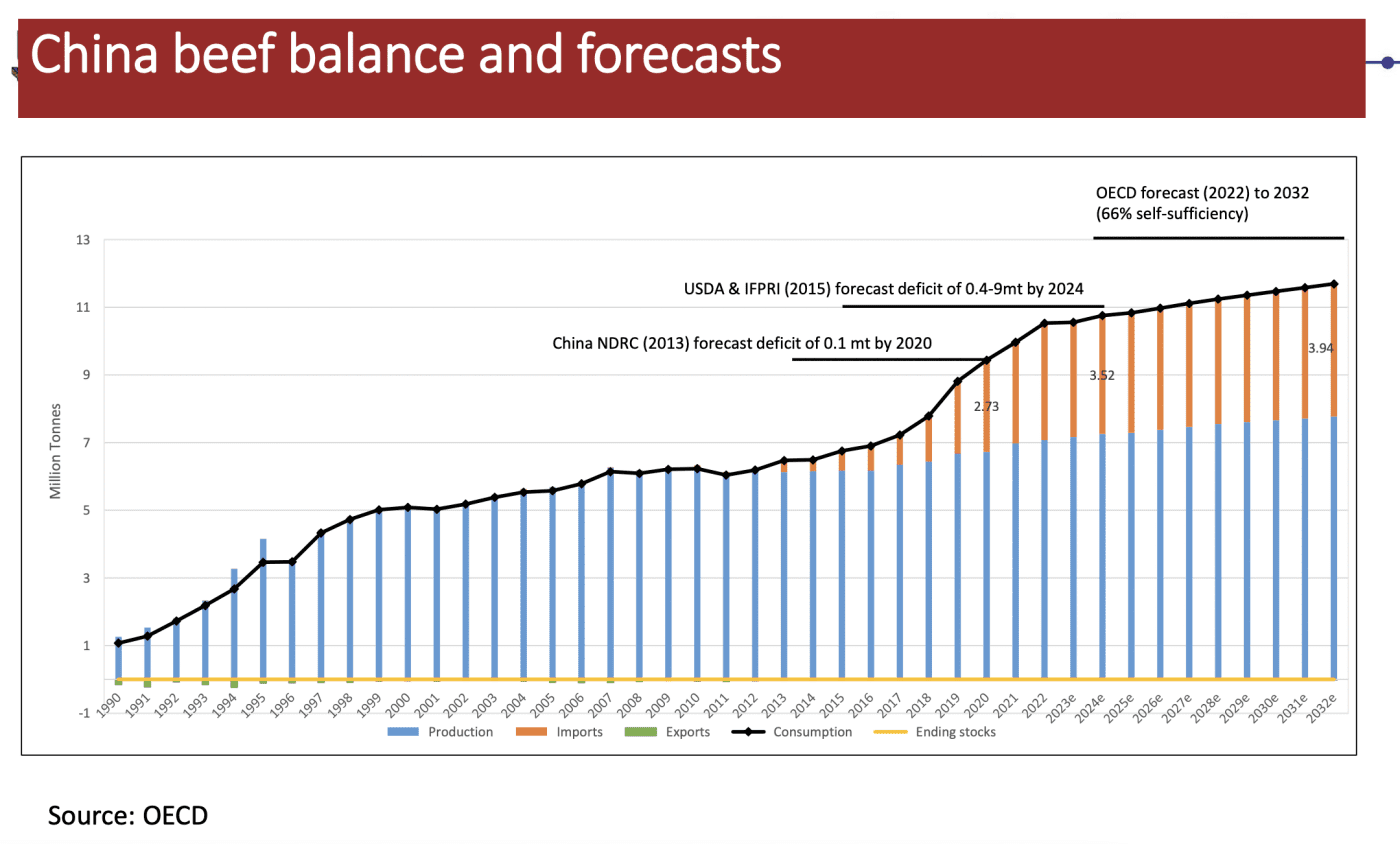

The gap between China’s domestic beef production and consumption is projected to grow to about four million tonnes per year by 2032 – a volume equivalent to about two times Australia’s total annual beef exports per year.

Australia has been a major supplier of beef to China over the past decade, but how big a role it will play in helping to bridge China’s beef deficit in future remains shrouded in a trade policy climate that is as complex as it is unclear.

Australian agricultural exports to China have always been subject to a range of barriers in the Chinese market.

But until a few years ago, agricultural trade issues between the two trading partners were short-lived and usually resolved within months, University of Queensland Associate Professor Scott Waldron told a China Beef Policy Briefing in Brisbane last week.

The current situation is different, with seven Australian beef export abattoirs still without export licenses to China more than four years after they were suspended for a range of technical mislabelling or product certification reasons.

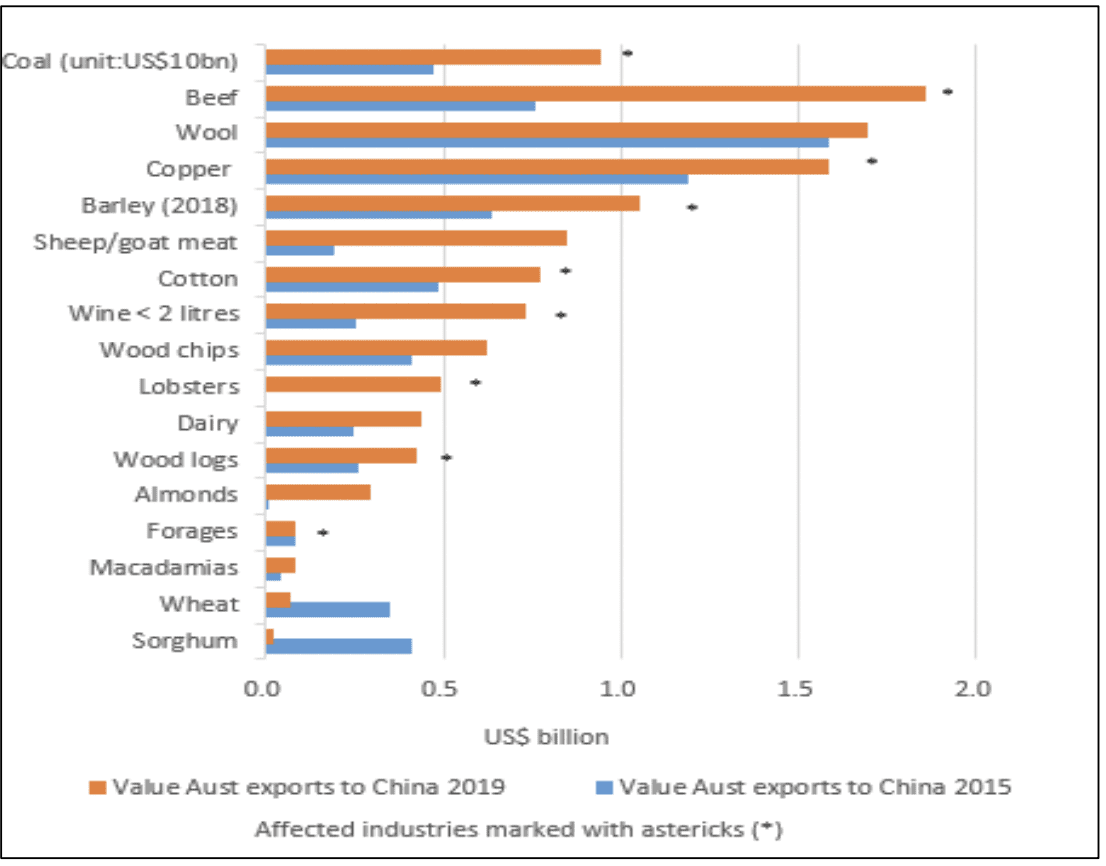

Beef was one of nine Australian agricultural commodities that China imposed a raft of trade barriers upon from May 2020, measures which were widely regarded as punishment for Australian Government decisions relating to China since 2017, such as barring Chinese-owned telecommunications giant Huawei from rolling out Australia’s 5G network and calling for an independent investigation into the origins of COVID 19 in China.

China has since lifted suspensions on some commodities such as Australian wine and barley, and also three Australian beef abattoirs in December 2023 which had been suspended after self-reporting Covid infections among staff in 2020.

However sanctions on seven Australian beef abattoirs remain in place with no sign of a resolution yet to emerge.

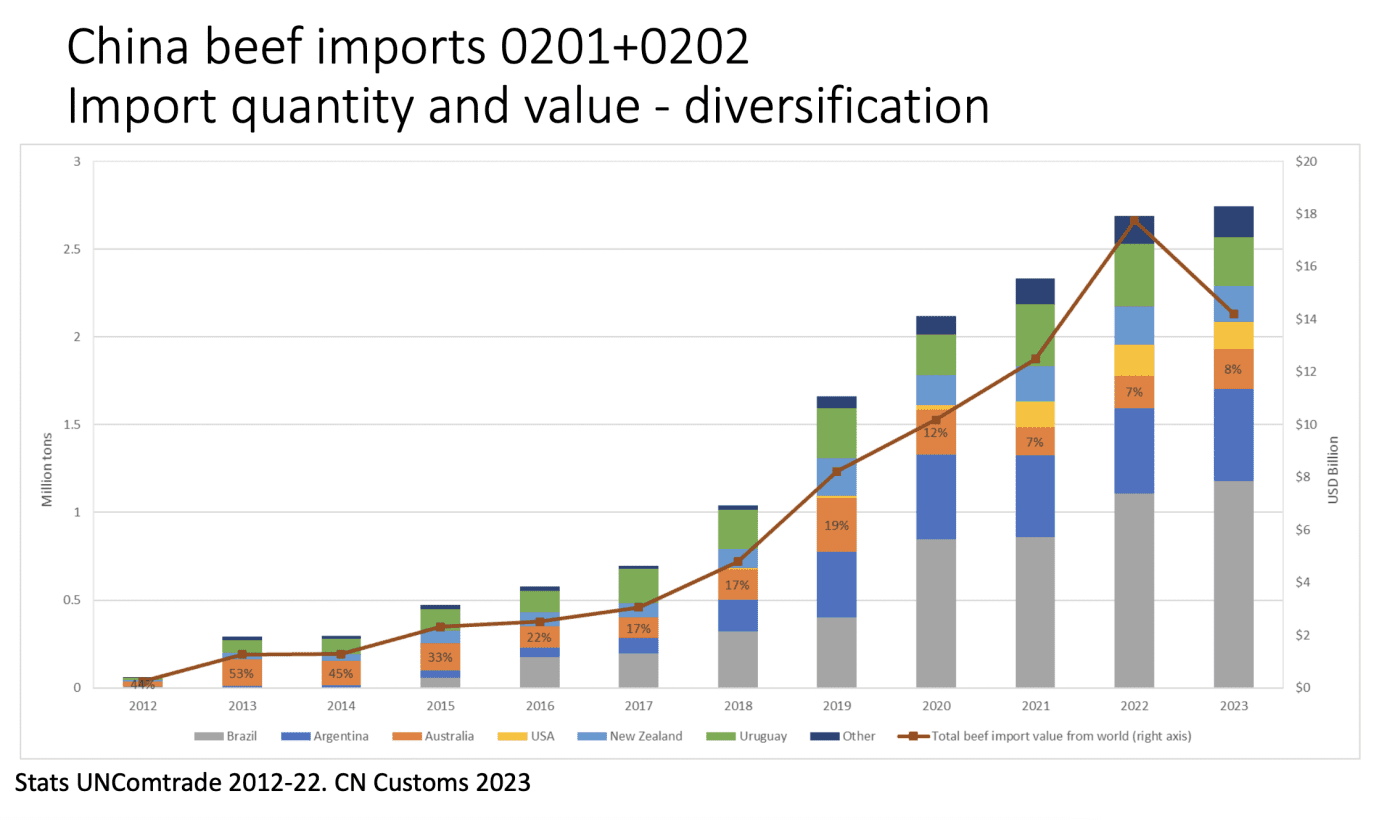

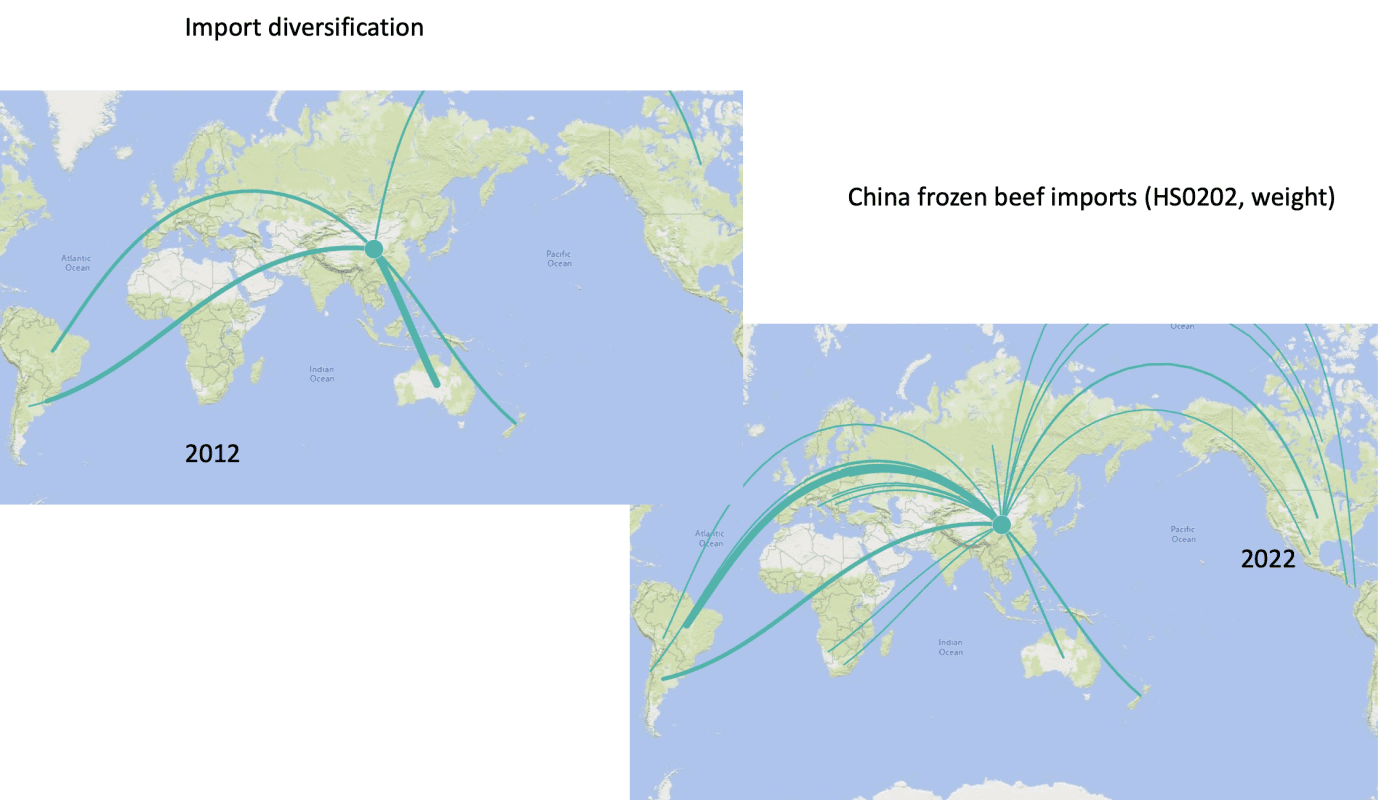

At the same time China has also granted import permits to many other beef export abattoirs in countries such as the US, South American beef exporting nations and New Zealand, as it moves to substantially diversify its beef imports away from concentrated sources such as Australia (as illustrated by the maps below).

Maps showing the diversification of China’s sources of frozen imported beef between 2012 and 2022. Source: Dr Scott Waldron, UQ

Last week’s Brisbane briefing for a gathering of meat processing, exporting, lot feeding and Government representatives was held as part of a project funded by the National Foundation for Australia China Relations, a body under the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

The project involves experienced China-Australia trade policy experts Associate Professor Scott Waldron and Dr Jing Zhang from the China Agricultural Economics Group at the University of Queensland, and is co-led by Associate Professor Ben Lyons and Ms Fynn De Daunton from the Rural Economies Centre at the University of Southern Queensland. The project provides in-depth analysis of China’s food security, agricultural and trade policies to inform the decision-making of Australian agricultural companies and organisations.

Economic coercion

China’s actions in imposing sanctions against Australia’s nine largest agricultural export commodities in a short period were an example of economic coercion, where the sender country aims to impose economic costs on the target country to change its behaviour or policy.

“While China’s form of coercion is informal, where objectives are not explicitly stated, that is what we think was the objective,” Dr Waldron said.

“Economic coercion is the primary explanation of what was going on for beef.”

There were also reasons why agriculture was targeted over other economic sectors.

“Agriculture is really heavily targeted by China in its international coercion campaigns, because, firstly, agricultural producers are thought to be influential, and, secondly, because of plausible deniability,” Dr Waldron said.

“China can say ‘this is not coercion, we actually found bugs in your logs and we will show you the sample’, so most Chinese coercion is targeted at agriculture.”

In 2020 China effectively began working its way down a list (below) of Australia’s largest agricultural exports, starting with the biggest – beef – and using technical reasons such as mislabelling or certification issues as justification.

Did China’s economic coercion strategy succeed?

Despite the impact on Australian beef, and the fears at the time that China’s campaign of economic coercion could badly damage Australia’s export-dependent economy, the overall take home message is that did not happen.

While exports to China did flatline, and suspended exporters of premium Australian beef would no doubt have preferred to retain access, Australian agricultural exports increased enormously to other countries around the world, with China’s actions ultimately having a lower impact than initially feared by Australia.

“Which means that this coercive instrument wasn’t successful, Australia withstood the political pressure from it,” Dr Waldron said.

China faces growing deficit in beef

Dr Waldron said food security has become a prominent driver of Chinese trade policy under President Xi Jinping.

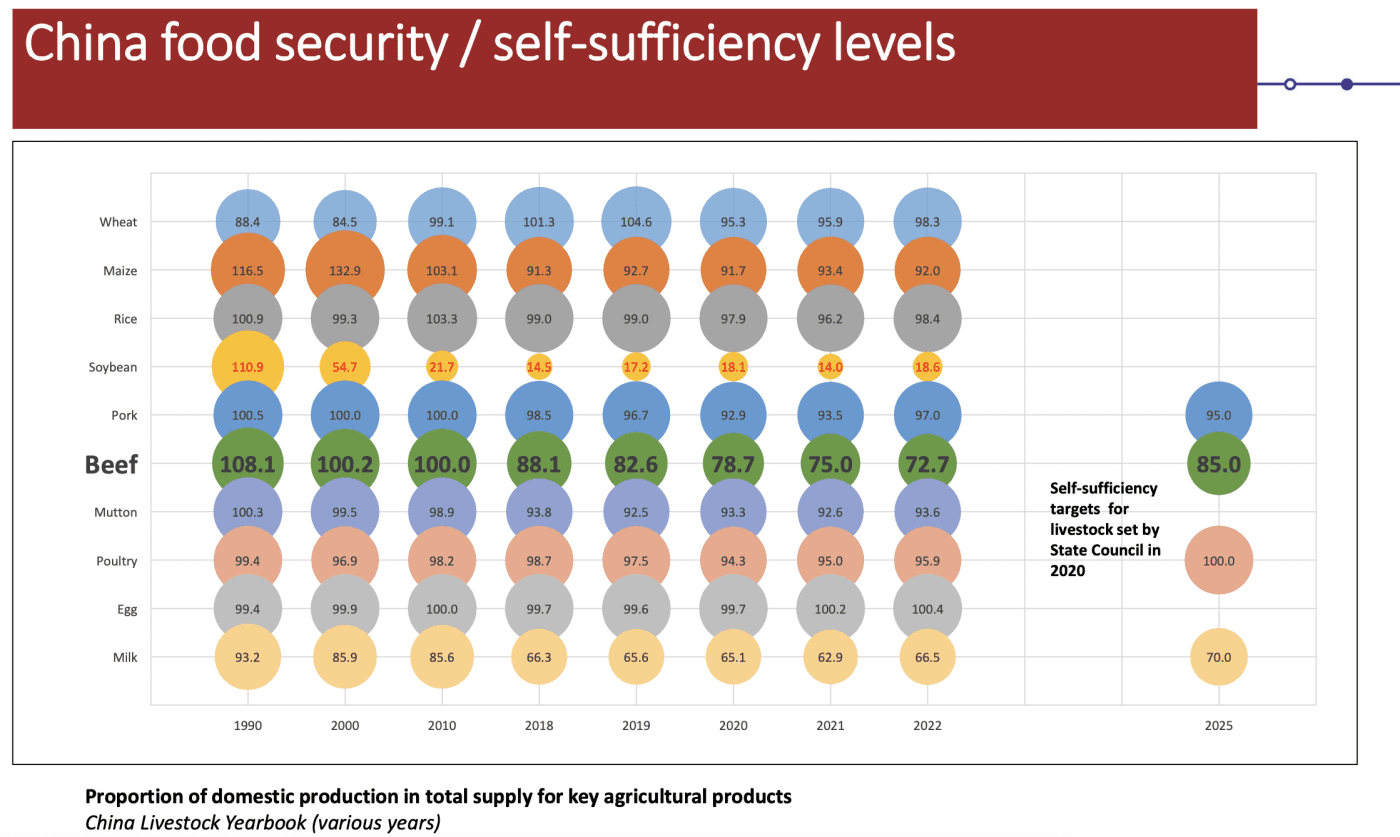

China has introduced a range of mechanisms to improve agricultural productivity and self-sufficiency in key commodities such as poultry and pork.

China also wants to achieve minimum levels of self reliance in commodities such as grains (95pc), beef (85pc) and dairy (70pc), but is facing growing deficits especially in the feed and ruminant livestock sectors.

Cow-calf production in particular is not an economically favourable proposition in China.

“Any country with a decent breeding herd has either got a lot of land or a very low labour cost, and China has got neither and that is the constraint,” Dr Waldron said.

Small farms with two cows could operate when labour costs were low, but now rising urban and rural incomes mean the labour cost of raising cattle is too high.

“So that is why China will never be self-sufficient or close to 85pc of its objective.”

Competition for land use is also growing.

“There are Government officials in China now telling farmers to pull up their horticultural crops – apples and oranges and so on – to grow soybeans and corn, because that better fits the food security aims.

“There is no one running around telling farmers to add more beef cattle, it is just not as strategically important, and the money is just not in it.”

Illustrating the structural change away from small-scale beef cattle production, Shandong Province between Beijing and Shanghai was once the biggest cattle producing province in China.

But 93pc of the small households that turned off 1 to 9 head per year have exited the industry. Increased scale and commercialisation is occurring however, with increases in larger scale sectors, such as feedlots turning off 500 to 1000 head per year, and overall carcase weights also increasing.

Another structural trend that is impacting domestically produced beef supply has been an enormous decline in the number of draught cattle used in China for farming, as small farmers have adopted tillers and small tractors to save labour.

China has the third biggest cattle population in the world, but its domestic herd has been declining in size for several years.

OECD forecasts of China’s domestic beef production versus beef consumption estimate that by 2032, China will have an estimated deficit of four million tonnes of beef per year.

China is trying to achieve a tricky balance juggling competing objectives of self-sufficiency and import diversification, Dr Waldron said.

Trade agreements such as ChAFTA have reduced incentives for exporters and importers to use grey channels to bring beef into China, such as through Hong Kong, while Chinese crackdowns on the same channels for anti-corruption and border security reasons have also seen the informal trade largely stop.

One ongoing issue for Australian beef exports to China for those plants that are certified falls under the banner of informal non-tariff barriers in the form of food refusals or food hold ups.

This can involve beef containers from one country such as Australia being subjected to far more scrutiny and delays by customs officials than imports from other countries, a form of trade barrier which is invisible and outside trade rules but which can heavily impact the target country.

Feedback from Australian exporters present suggested this is an ongoing problem for Australian product into China, with customs delays reducing the willingness to export chilled product in particular until it is resolved.