David Williams addresses the Brisbane audience

FORGET chicken and pork, highly-efficient aquaculture shapes up as beef’s big animal protein threat in coming decades, says financial guru David Williams.

Speaking at a beef industry event hosted by CBRE Agribusiness during Brisbane show earlier this month, the head of Melbourne-based finance advisory firm Kidder Williams said the world was producing and eating more animal protein, but less beef.

But the beef industry could perhaps take some lessons from progress being made in the aquaculture industry, he suggested.

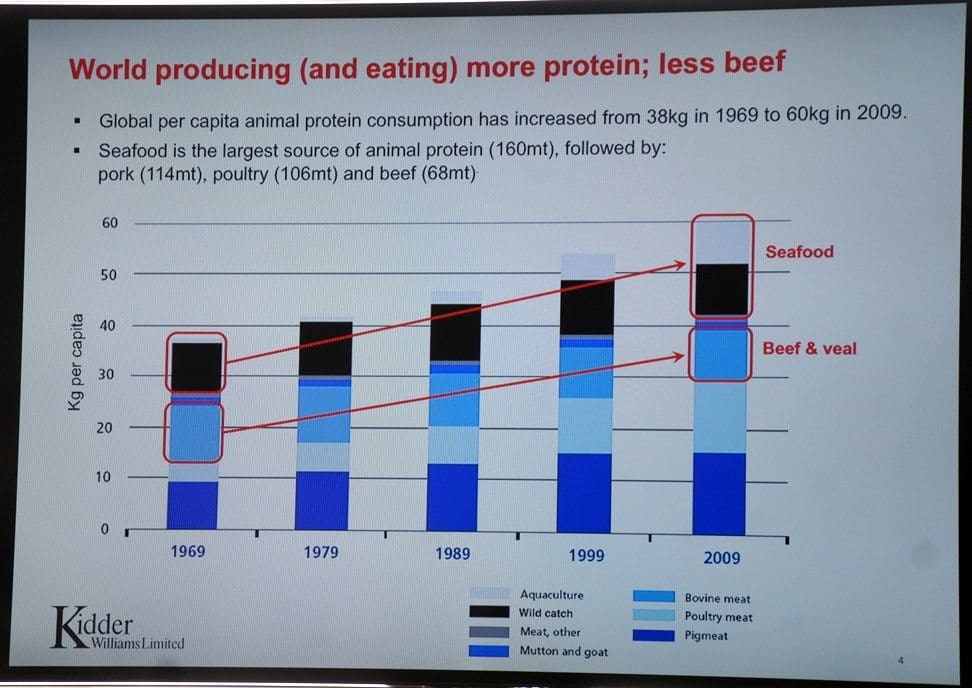

“Global per capita animal protein consumption has increased from 38kg in 1969, to 60kg in 2009. Of that, seafood is now easily the largest source of animal protein, representing 160 million tonnes each year,” Mr Williams said.

That was followed by pork (114mt), poultry (106mt) and beef, well back at 68mt.

Mr Williams speaks with some authority about the aquaculture industry’s prospects, having rescued Tasmanian farmed salmon producer Tassal from receivership, and pushing it after an IPO into its current position as by far Australia’s largest fish farming business. Tassal this year expects to make a profit of $83 million, on turnover of more than 30,000 tonnes of salmon and salmon products. Putting aside Huon Aquaculture, Tassal was bigger than every other aquaculture business in Australia combined, in terms of profit, he claimed.

He lived up to his reputation as a lively, entertaining and thought-provoking speaker, providing the Brisbane beef producer audience with some interesting comparisons to ponder between progress being made in the beef industry versus the farmed seafood industry.

So where does beef currently sit in terms of other proteins around the world?

“Pork is increasing over the past 20 years, chicken is increasing dramatically, beef is going down, and seafood has doubled. It is now far and away the largest source of animal protein worldwide,” Mr Williams said.

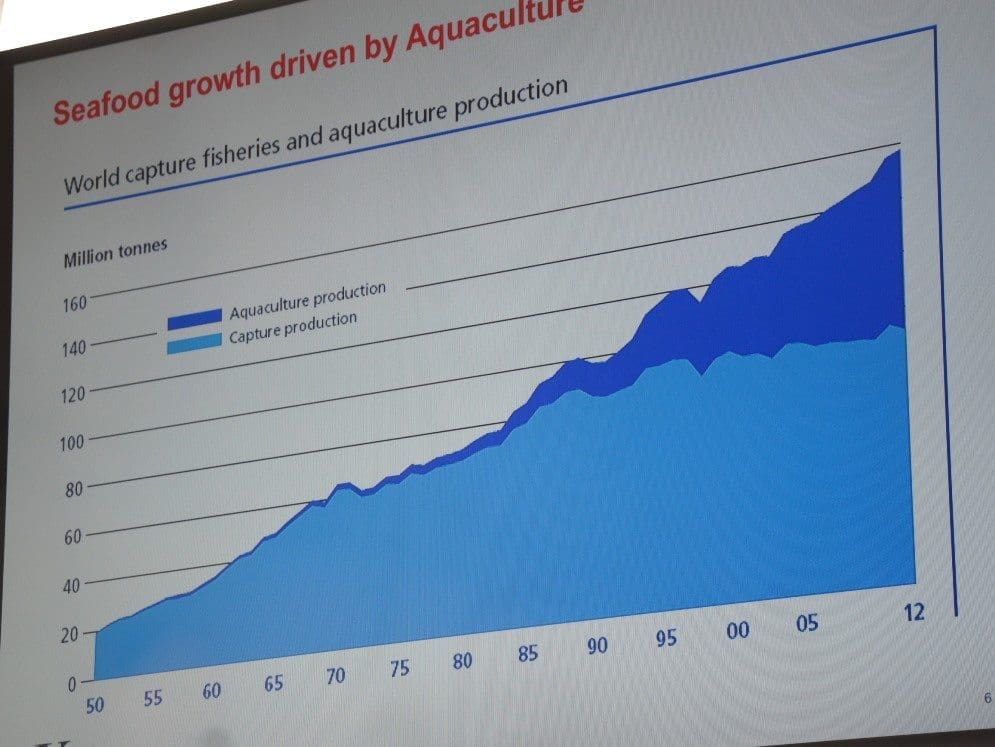

He pointed to an important trend in seafood production, being the growth in farmed seafood, as opposed to wild-caught fish.

“We all know what’s happening with wild-catch. Everywhere around the world, regulation is being applied to limit boat sizes, net sizes and number of fishing licences. In the main, wild-catch is stabilised at best, or shrinking – so all of the growth that’s being seen has been in aquaculture,” he said.

Since about 1990, as consumers and regulators became more focussed on wild stocks and animal welfare, wild catch had flattened out, and started to decline in places like Australia, due to regulation.

But that’s been more than compensated for by growth in aquaculture – largely fin-fish, rather that prawns and other seafood.

That trend can clearly be seen in the graph shown above, with aquaculture production worldwide (dark blue shaded area) starting to gain significance from around 1990, before growing into the large share of all seafood production it holds today.

But why has aquaculture exploded, at the same time as beef has struggled to maintain volume?

As a ‘humble fish farmer’ through Tassal, Mr Williams said one of the things he was thinking about every day of the week was how to produce fish more efficiently.

“I’m comparing Tassal’s performance with the other big Atlantic salmon producers around the world – the Chileans, the Scots and the Norwegians – in rate of gain and feed conversion ratio. Everybody in the farmed seafood industry thinks about these performance figures, along with branding, which most beef producers do not,” he said.

“But they’re two of the things that beef producers need to start thinking about more.”

Focus on ‘protein’ rather than species

Mr Williams said some of the biggest aquaculturists in the world he had spoken to were increasingly less interested in ‘species’, like salmon, tilapia, or catfish – than they were in focussing on ‘protein.’

“Nobody talked about ‘protein’ ten years ago. What the major aquaculture players are now targeting is growing protein as quickly and as efficiently as possible. The species is just the means to an end,” he said.

In the case of a fish like Tilapia, which was now a ‘hot’ species among fish farmers, a fingerling can be put in the water, and removed 18 months later at 3kg bodyweight. Other species can take twice as long to reach the same weight.

“So the focus in aquaculture is in growing things as quickly and efficiently as possible,” Mr Williams said.

Feed conversion progress

“It’s also worth looking at relative feed conversion efficiency between fish and other animal proteins. There have been massive gains in many farmed fish species – about 80 percent due to genetic improvement, but also 20pc from feed improvements and general farm management practises,” he said.

“When I bought Tassal ten years ago, our feed conversion efficiency in salmon was 1.6:1. That means we had to feed 1.6kg of feed in order to extract 1kg of fish weight. Now the feed conversion efficiency in salmon is down to 1.2:1. That lower feed conversion ratio drives the cost of production down.”

The feed ration that was used ten years ago was largely based on wild-caught low-value fish, like jack mackeral out of Chile. The ration now is largely made from canola and other omega 3-rich grains, algaes and ingredients other than wild-caught fish.

“Yet we have not seen those sort of feed conversion advances in cattle at all,” Mr Williams said. “Little baby steps, perhaps – but there is a big focus in the farmed seafood industry, and also in chicken and pork, on improving that feed conversion performance, through both genetics and feed.”

Depending on locations around the world, Mr Williams said salmon feed conversion ratios are currently between 1.2 and 1.4:1; barramundi are around 1.8:1; chicken 3:1; pork at 5 or 6:1; and beef, 7 to 8:1.

“These are some of the things the beef industry needs to think about,” he said.

He also contrasted price changes over time in different animal proteins, as part of the explanation behind momentum in aquaculture.

Figures presented for domestic retail meat prices showed beef jumping 83pc over the 25 years ending 2015 by 83pc; lamb up by 154pc and chicken by just 10pc.

“But relative prices are interesting. Salmon, for example, I’m selling that into the market at $12-$14/kg – about the same as what it was ten years ago. Real prices for salmon, or barramundi, or whatever, are not changing much, while red meat has increased very significantly.”

China big driver

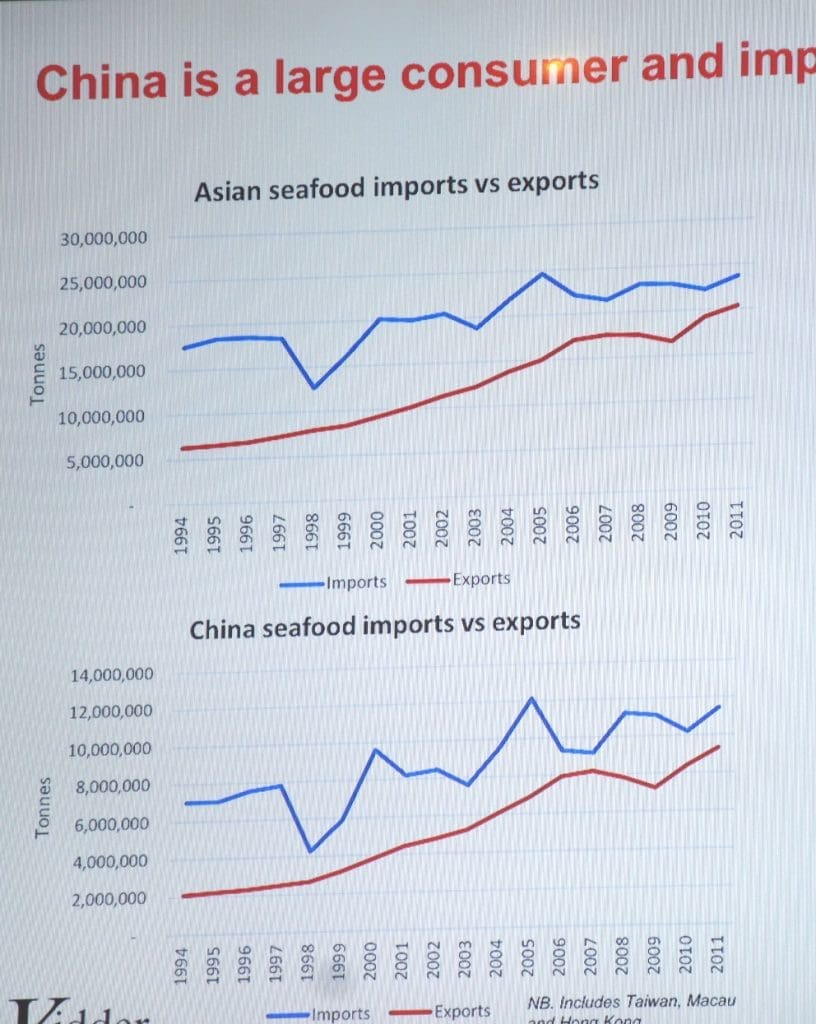

Mr Williams also highlighted the impact China’s growing protein consumption was having on the world food trade, but particularly in seafood, it was driving the industry “like you wouldn’t believe.”

Using 2012 figures, he said China produced about 41 million tonnes of farmed seafood, or 62pc of the world total each year. Next largest was India, with 6pc of the world’s farmed seafood, and Vietnam and Indonesia, with 5pc each.

“China is easily the largest producer of inland farmed fish, crustaceans and molluscs; and it is already the second largest producer of sea-farmed fin-fish after Norway. Within the next few years, China’s growth in farmed seafood will see it become a large net exporter of seafood into the rest of the world,” Mr Williams said.

Similarly, across the entire Asian region, seafood exports were now drawing close to import volumes, suggesting the region would soon become a net exporter, shifting protein into more of the Australian beef industry’s traditional markets.

Mr Williams said the ‘clean green’ image that Australian beef coveted meant little in some markets, when Asian seafood could be produced and exported so cheaply.