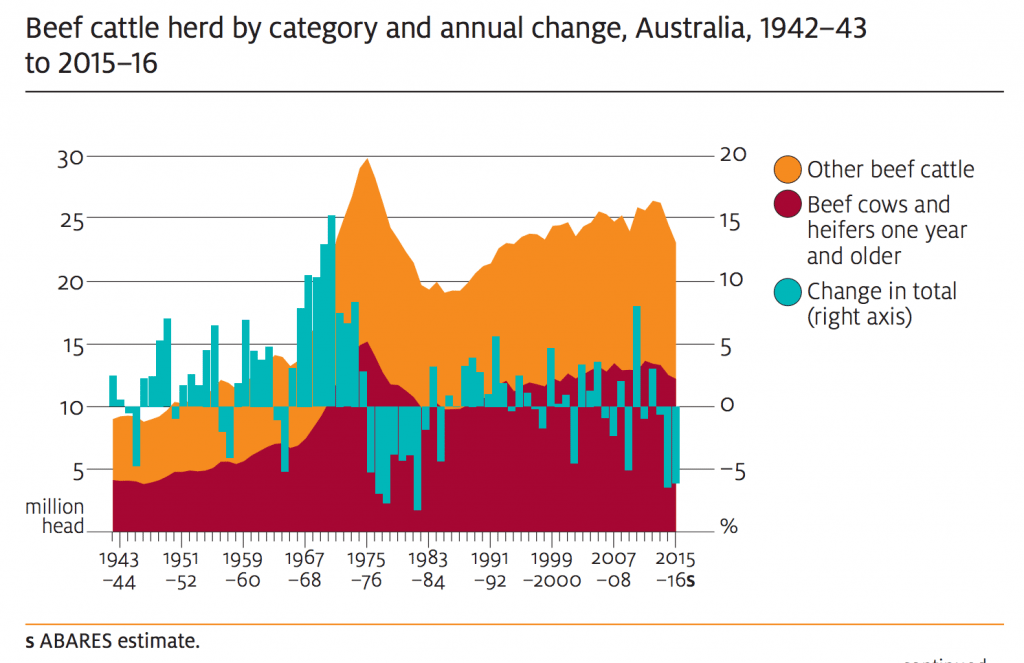

The Australian beef cattle inventory declined by around 10 per cent in the four years to June 2016, to an estimated 23.3 million head.

This represents the largest decline in the national herd since the 1970s and is a direct result of the high turn-off that occurred between 2012–13 and 2015–16.

The increase in turn-off was initially in response to hot and dry conditions across eastern Australia, which limited pasture growth and reduced the carrying capacity of graziers in those regions.

Since early 2014, strong export demand has driven Australian saleyard prices up sharply, resulting in continuing high turn-off.

Despite forecast lower slaughter in 2016–17, turn-off is still expected to exceed additions to the herd.

As a result, a further slight decline in beef cattle numbers is forecast in 2016–17.

Herd rebuilding is expected in the years immediately following, assuming improved seasonal conditions, which will lead to a rise in cattle numbers.

However, the rate of increase is likely to be gradual because a small female cattle inventory will restrict the number of calves born.

Seasonal conditions will shape the dynamics of the Australian beef cattle herd by affecting both the number of additions to the herd and the rate of turn-off.

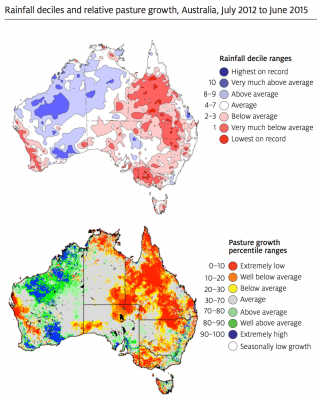

Poor seasonal conditions combined with strong export demand led to high cattle turn-off From 2012–13 to 2014–15, rainfall was below average in all states and territories except Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

Many areas recorded their lowest rainfall on record and rainfall deficiencies were particularly extensive in Queensland, the largest beef-producing state in Australia.

Temperatures were generally above average during this period, and most of central Australia registered record temperature anomalies in 2013–14.

The combination of hot and dry seasonal conditions between 2012–13 and 2014–15 limited pasture growth in Australia’s major beef-producing regions.

In response, cattle turn-off increased sharply beginning in 2012–13.

Pasture growth in Queensland was extremely low over the 36-month period, which reduced the carrying capacity of affected grazing properties.

International demand for Australian beef exports drove saleyard prices up sharply after January 2014, which gave producers an incentive to maintain a high rate of turn-off through 2015–16.

Slaughter rates rose in every state and territory during the four years to 2015–16.

The largest increase occurred in Queensland, which accounted for around 45 per cent of national slaughter during the period.

Live cattle exports also rose strongly over the period. In 2015–16 the number of live cattle exported from Australia is estimated to be 1.32 million head—almost double the 683 000 head shipped in 2011–12.

Largest herd contraction since the mid 1980s

The sustained period of high cattle turn-off has resulted in a marked reduction in the national beef cattle inventory, which is estimated to fall to 23.3 million head at 30 June 2016.

This is a decline of 9.5 per cent when compared with the 2011–12 closing inventory of 25.7 million head and the smallest closing inventory since 1994–95.

This contraction represents the largest and most sustained reduction in cattle numbers since the decline of the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the national beef cattle herd shrank from a peak of almost 30 million head in 1976 to a low of around 19 million head in 1984.

During that period, Australian saleyard prices collapsed as export demand for beef declined in response to weaker global economic conditions and strong competition from other international beef suppliers in key Australian export markets.

Australia also lost the United Kingdom as a major export market when it joined the European Common Market in January 1973.

After the mid 1980s the Australian beef cattle herd grew steadily, expanding on average by 1 per cent a year over the 1990s and 2000s to peak at 26.5 million head at 30 June 2013.

The national herd contracted eight times during this phase of steady expansion. On average, the national herd fell by 2.6 per cent in these contractions.

The largest reduction in numbers occurred in 2009–10, when the beef cattle inventory fell by 5.1 per cent or 1.29 million head to 24 million head.

The periods of contraction over the 1990s and 2000s were relatively short-lived, generally lasting a single year before the national herd expanded again.

In the expansion years that immediately followed contractions, the increase in cattle numbers was generally greater than the preceding decline and resulted in a net expansion of the herd.

For example, after the 2009–10 contraction of 1.29 million head, the herd grew by 1.93 million head (8 per cent) the following year—a net increase of 0.64 million head.

Additions limited by reduced cow inventory and low branding rates

In contrast with circumstances in the 1990s and 2000s, the current composition of the national herd is expected to limit the capacity for cattle numbers to expand quickly over the short to medium term.

This is because the number of cows and heifers has declined significantly since 2011–12, falling to an estimated 12.3 million head at 30 June 2016.

This represents the smallest closing breeding inventory since 2000–01 and is comparable to the 1993–94 closing inventory.

Almost a third of the opening beef cow and heifer inventory was slaughtered in each of the four years to 2015–16.

Female cattle slaughter peaked in 2014–15 at 4.76 million head, the second-largest annual female cattle slaughter on record.

The reduction in cow and heifer numbers by 1.3 million between 2012–13 and 2015–16 is around three times greater than any other contraction since the mid 1980s.

The small breeding cow inventory will limit the number of calves born in 2016–17 and in the years immediately following.

However, cow fertility and calf death rates are equally significant in determining the number of calves that survive to be added to the herd.

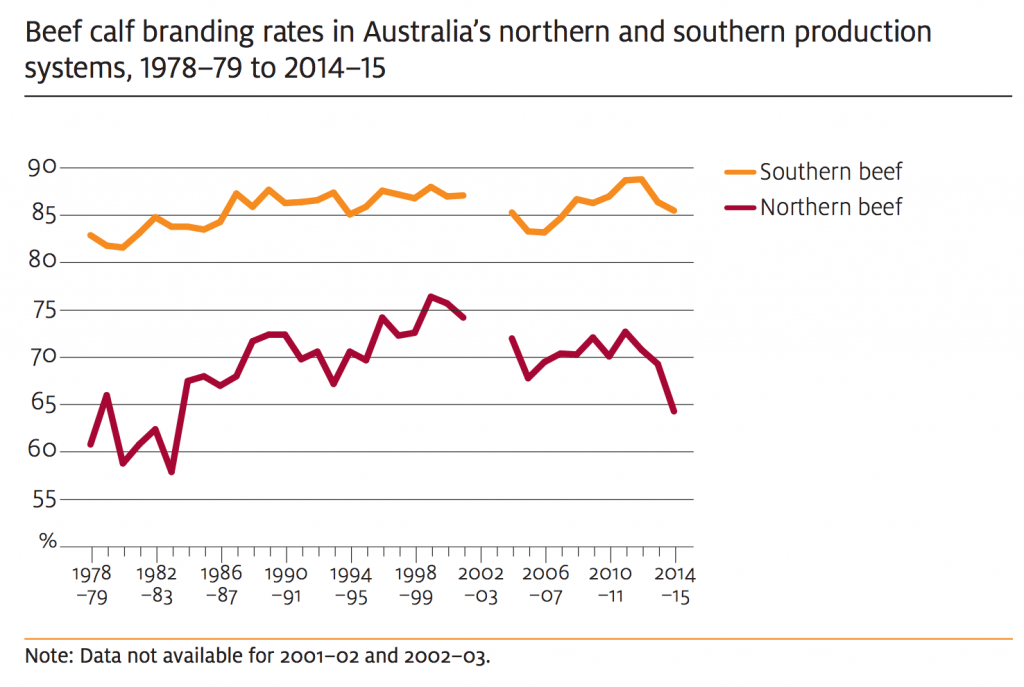

The branding rate is the ratio of surviving calves to the number of cows mated and provides an indicator of cow fertility and calf mortality, both being strongly influenced by seasonal conditions.

Successive years of hot and dry seasonal conditions between 2012–13 and 2014–15 adversely affected branding rates across Australia, particularly in Queensland.

In 2014–15 the average branding rate for herds in northern Australia fell to 64.3 per cent, the lowest since 1983–84.

This means that only two-thirds of cows mated in northern Australia produced a calf that survived to be added to the herd.

In the same year, branding rates in southern Australia fell to around 85.5 per cent, from a peak of 88.8 per cent in 2012–13.

In 2015–16 average branding rates are assumed to remain low across Australia. This is mainly a result of below-average seasonal conditions in major beef-producing regions, particularly central Queensland.

Herd rebuilding is expected to be gradual

In 2016–17 an assumed improvement in seasonal conditions is expected to result in an increase in average branding rates across Australia.

However, the total number of calves born during 2016–17 will remain limited by the lower opening cow inventory. Around nine million calves are forecast to be added to the national herd in 2016–17, 5 per cent fewer than the annual average over the five years to 2011–12.

Cattle turn-off is forecast to exceed the number of additions in 2016–17, despite a marked decline in cattle slaughter.

This would be the fourth consecutive year of decline and is forecast to result in the national beef cattle herd falling to around 23.1 million head.

After 2016–17 the national beef cattle herd is projected to expand as calf additions begin to exceed turn-off.

Initially, the rate of expansion is expected to be gradual because of the small breeding cow inventory.

The rate of expansion will rise as the breeding cow inventory grows, increasing the number of calves born annually.

However, recently born female calves will be unable to bear calves for two to three years, which will limit the expansion of the breeding cow inventory in the short term.

For the breeding cow inventory to continue expanding over the medium term, cow and heifer turn-off must remain relatively low.

If seasonal conditions are less favourable than currently assumed, producers will have an incentive to maintain a higher rate of turn-off than currently forecast.

Source: ABARES. To read the full Agricultural commodities: June quarter 2016 report click here