BEYOND all the rejoicing and political chest-beating around Saturday’s announcement about Australia’s new Free Trade Agreement with the UK, it’s worth taking a deeper dive into what the agreement actually means, and how the new trade is likely to play out in coming years.

The UK beef market will be open for business for Australia from 1 June, and already one beef export processor has lifted its premium for EU-eligible cattle in response.

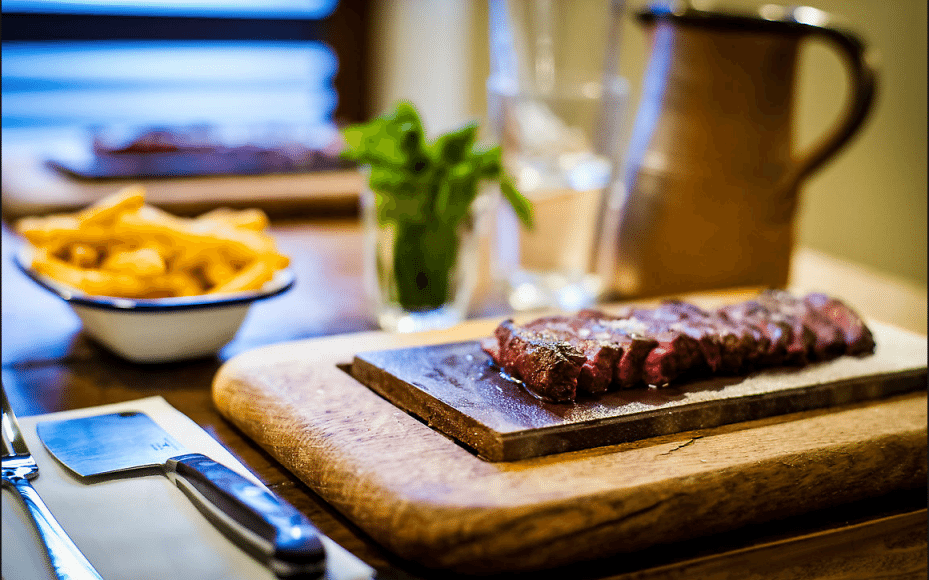

Australian flat iron steak (seamed oyster blade) in a UK steak restaurant

But first, a bit of history. For decades the EU (then including the UK) has been one of the highest-value markets for Australian beef, but equally has always been greatly constricted by quota access.

The original Hilton HQ (mostly grassfed) quota was limited to just 7150 tonnes each year, while the more recent Grainfed quota (Australia piggy-backed into that trade opportunity via a deal struck between the EU and the US to stop the US pursuing the EU through the World Trade Organisation over the legitimacy of its HGP bans) was shared with the US.

And supplying the EU trade was not only restricted to HGP-free beef, but cattle sourced from properties embedded in the restrictive EUCAS accreditation process, involving annual audits and cattle movement limitations.

All that changed with BREXIT, however, when the UK left the EU in February 2020.

That has led to the bilateral FTA deal Australia has now been struck with the UK, which comes into effect from 1 June. Since the UK left the EU, all Australian beef entering the UK has been subject to full tariffs and charges.

Firstly, a brief explanation of how the new access arrangements will work.

This year (2023) the UK tariff-free beef quota volume is 35,000t. But because the trade is due to commence only from 1 June, this year’s volume is applied pro-rata (i.e. seven months out of twelve), meaning we will have access for just over 20,600t for the remainder of this year.

After 2023, tariff-free volume will rise by roughly 8000t per year, for the next nine years. Next year, for example, the tariff-free quota rises to 43,333t, followed by 51,667t the year after that. By year ten, Australia will have access for 110,000t of beef, tariff free, and by the final stage of the agreement in 2037, the quota will have reached 170,000t.

Prior to the FTA, the base rate for Australian product was a 12pc tariff, plus 253 British Pounds per 100kg. While it is highly unlikely, given the size of Australia’s new quota, any product shipped after an annual quota is filled would be subject to the tariffs and charges listed above.

A Safeguard mechanism, not unlike that applied in Australia’s export to Japan, Korea and the US, will apply to avoid distortions caused by unusually large jumps in trade from year to year.

Access to the quota will be administered via a split allocation system and a first-come, first-served basis until the available quota amount is exhausted.

Trade goes to sleep

Beef trade with both the EU and the UK has basically fizzled out for Australian exporters over the past two years, in the absence of a working FTA with either.

Last calendar year, our trade to the UK totalled just 741 tonnes, and the remainder of the EU, just 6300t. That ranked the UK in volume terms only marginally ahead of Mauritius, and about 20pc of the size of Australia’s trade with near neighbour, Papua New Guinea.

Things were only slightly better a year earlier, with Australia’s total trade to the UK that year topping 1027t, and 1500t the year before that. You have to go back to 2018-19 to find any significant volume into the UK, reaching around 4400t both years.

New horizon

The considerable size (relative to our historic access) of the new tariff-free trade means several things for Australian exports.

Firstly, under the old Hilton and GF quotas, the volume limitation meant that the best strategy for exporters was to use each shipment for high-value cuts only.

That no longer applies, with a much broader range of items, including trim for grinding beef, now likely to find its way into the UK market, provided eligible supply is available.

Supply-side challenges

Despite the fact that the UK has not been a part of the EU for three years, it continues to operate under the EUCAS system for Australian beef imports.

However it is clear from discussions and email correspondence with some Beef Central readers since Monday that some stakeholders have incorrectly assumed that because the UK is no longer part of the EU, that the EUCAS accreditation model no longer applies.

In other countries, like China, where Australian beef supply is limited to HGP-free only, a simple NVD declaration applies to exports.

The current limitation to beef from EUCAS-accredited Australian beef producers only means that in the early stages at least, Australia’s supply capacity is likely to be significantly limited.

‘EU’ premiums start to stir

During the past two years while very little Australian beef has found its way into the EU or UK in the absence of FTAs, cattle premiums on offer for going to the added expense and effort to comply with EUCAS have largely disappeared.

Premiums of 50-60c/kg (at times, as much as a dollar) were often paid in the past, when the trade was active. But over the past two years of dormant trade, that premium has frequently been as little as 10c/kg over an HGP-free 0-4 tooth MSA grass bullock.

However one large Eastern Australian export beef processor as recently as two weeks ago lifted its ‘EU premium’ (effectively HGP-free cattle qualifying under EUCAS) to 35c/kg. That’s compared with an MSA steer, HGP-free, 0-4 teeth. That company currently kills only a small number of EU-eligible cattle at two of its plants each week, but has killed for the EU market at up to four company sites in the past.

It’s hard not to interpret that grid price rise as being linked to the UK FTA deal announced on Saturday.

A company spokesman told Beef Central it was designed to ‘try to keep people (producers) in the EUCAS system,’ despite the recent lack of volume and price incentive.

He said demand out of the remainder of the EU region had also recently gotten a little stronger for trade out of Australia, despite the tariff impact being applied.

“We want to try to fill some of those orders, but also to try to reinforce to people that it is worth staying in the EUCAS system, despite the challenges,” he said.

Another large processor estimated that only around a half to two thirds of Australian producers who once operated under EUCAS still did so, because of the lack of market activity recently.

Another processor said his company continued to offer a small premium for EUCAS cattle, worth about 20c/kg on top of the normal grid, because his company wanted to ‘hang-in there, because we know there’s future potential in it.”

“We’ve been just trying to keep the linkages going, but very small volume,” he said.

Asked by Beef Central whether he was aware of many producers abandoning their EUCAS accreditation he said the following:

“Our line has been we’ve encouraged them to stay in the program, if it’s not costing them too much, because of what might happen down the track. We think that will lend itself to the new opportunities happening from next month.”

Another large Queensland beef supply chain manager said while many of its former EU cattle suppliers had retained their EUCAS status, most of that product had in recent times found its way into his company’s No-HGP certified grassfed beef brands, destined for various other markets including China.

“Those former EU cattle have largely been diverted into other HGP-free premium brand programs,” he said. “They felt it was easier to keep the accreditation, even if it wasn’t being used, rather than leave, and then try to get the accreditation back.”

What type of Australian product will the UK be looking for?

London-based UK meat importer Des Marshall has had strong relationships with Australian exporters for more than 40 years. He originally worked with Sanger, which had multiple offices around the world – one of which was Sanger Australia. He later starting his own business, Mulberry International.

Des Marshall

He said the trade out of Australia had gradually shifted from frozen to chilled over the years, establishing a great market reputation for quality, consistency and shelf-life.

In an earlier response to concerns from British farmers that Australian beef and lamb could swamp the UK market from the moment the Australia-UK Free Trade Agreement takes effect, Mr Marshall described that possibility as highly unlikely.

He predicts the increased level of trade enabled under the agreement would take time to develop and will be more “slow burn” than explosive growth.

“Because of the restrictions through quotas and the need to make every tonne count, the type of Australian product we’ve seen in the UK has been first class,” he said.

Much of it had found its way into the food service sector and catering trade, for use in hotels, pubs, clubs and restaurants.

But now that a larger 35,000t tariff-free quota was starting from June, and growing year-on-year, a broader range of Australian beef items was likely to be seen.

“The UK imports around 200,000t of Irish beef each year,” Mr Marshall said.

“I think over time, price permitting, Australian beef will displace some of that Irish product,” he said.

Because Australia has in recent times been shipping high quality beef under the grainfed and Hilton HQ quotas, that will again be popular, because food service customers recognised it, knew it, trusted it and liked it, Mr Marshall said.

But with the FTA, there was now the opportunity for a broader range of cuts, and all grades of beef, including items like trim and bone-in beef, because it is no longer constricted by the tight quota.

“Under the old restrictive 7150t Hilton quota, exporters would obviously maximise their profitability by sending only a limited range of higher-value cuts.

“But we could even see some Australian cow beef for the first time in future – that could not happen under the previous quota, which was limited only to steer beef 0-4 teeth.”

He said the UK’s large burger manufacturers were unlikely to use Australian trim in their blends, because they mostly operated under a ‘UK-only’ (British or Irish) policy.

But some of the smaller independent manufacturers would likely have interest in Australian frozen trim supply.

Another potential challenge for the trimmings market is that UK laws do not permit blending of UK trim with imported – it must be one or the other.

“Price dependent, I see a wide range of Australian beef coming in – subject to supply,” Mr Marshall said. “The pubs and clubs market, for example could be a good graded cow beef product.

“Australia also has these new MSA categories like Eating Quality Guaranteed, allowing beef from older animals and cows, provided it meets MSA requirements. That may struggle initially, because people won’t necessarily trust it. They’ve never seen it, thinking ‘cow beef is cow beef.’ But feed it in on a drip-feed basis, and customers get to like it and trust it, it will work – especially while the UK faces its current cost-of living crisis.”

“Australia will be able to supply better value cuts like this, and that will work across the board.”

At the other end, Australian Wagyu was likely to become more common, leveraging off the fact that Australian beef is trusted and liked, especially in the food service market.

Even some of the larger UK supermarket retailers, like Morrisons, which had a history of using Australian beef in the past, could benefit from the FTA.

“There were times of year in the past when Morrisons would literally run out of Australian beef, because the import quota had been filled,” he said.

“There might well be the opportunity again in the retail market, especially while Uruguay and Argentina do not have the quota access that Australia will enjoy from next month.”

“The UK customers in the past always trusted the Australian product for its quality, shelf-life and consistency. Now they can trust it, also, for its continuity of supply,” Mr Marshall said.

“Even though shipping times for South American beef may be only three weeks, versus six weeks for Australia, the Australian chilled product has a far superior 140-day shelf life – and the UK market is clearly aware of that.”