LONG-HELD fears that the Wagyu beef industry may head into a period of over-supply – particularly for F1 feeder cattle of questionable genetic merit – are being realised, with some dramatic corrections being seen in the feeder market.

Discussion around prospects for over-supply in the Wagyu industry emerged during 2016, when it was clearly evident that very large numbers of young Wagyu Fullblood bulls were going into new commercial F1 programs.

Warnings followed from respected industry stakeholders like Don Mackay about the risks in breeding F1 cattle that did not closely match the characteristics being sought by lotfeeders running Wagyu programs in order to optimise consistency of marbling.

But some of those messages have apparently gone unheeded.

Beef Central has approached some of Australia’s largest Wagyu F1 supply chains, based in Queensland and New South Wales for this report. All were happy to contribute comment, but requested anonymity.

Attention-grabbing prices during 2016 for F1s around 670-700c/kg liveweight spurred a frenzy of demand, and subsequent high prices for young Wagyu bulls among commercial breeders looking to diversify, or move into Wagyu F1 production.

Based on discussions with five supply chains, which collectively feed about 50,000 Wagyu cattle at any one time, two main price trends have emerged:

- The market for all Wagyu F1s has suffered a substantial adjustment in the past 12-18 months , and

- A vast price gap has emerged this year between F1s carrying ‘desirable’ sire and dam side genetics, and others.

One large Queensland-based Wagyu F1 supply chain told Beef Central its current price for ‘well-bred’ F1s feeders 350-420kg was 520c/kg, down from 560c/kg just ten weeks ago. Another said it was paying 570c/kg for the ‘absolute best end’ of the F1s in the current market, for cattle it had paid 670c/kg for at the market peak; while another source quoted ‘better quality’ well-bred F1 steers carrying the right genetic background at 500c/kg liveweight this week, and 480c/kg for feeder heifers.

Compounding the demand-side issues is the fact that the nation’s largest F1 Wagyu producer, the Australian Agricultural Co, has recently changed its business model – now relying much less on bought F1 feeder cattle than it did this time last year.

In summary, those ‘better’ F1s have probably fallen 100-150c/kg in value since the earlier price peak.

“This time last year, those same steers were probably worth +600c. There’s just more feeders out there, of all descriptions, than what Wagyu lotfeeders can effectively utilise,” a supply chain manager said.

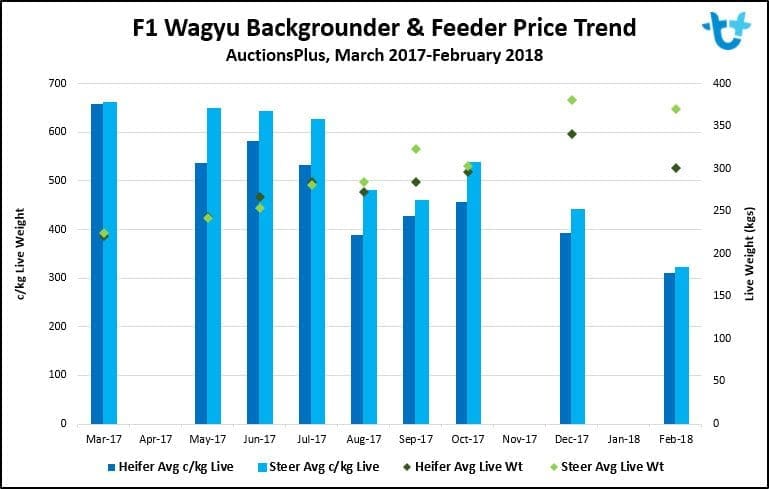

AuctionsPlus price trend in F1 Wagyu backgrounder and feeder steer and heifer price. Note graph makes no distinction on quality of F1s offered. Click on image to enlarge

Statistics show crossbred Wagyu steers, average weight 313kg, sold on AuctionsPlus back in the six month period to February 2017 averaged 659c/kg liveweight, and heifers 637c/kg.

Worth noting here is the fact that the market for Fullblood Wagyu feeders (100pc Japanese Wagyu sire and dam) has not been nearly as affected by the recent market slump for F1s. One large supply chain was still paying 700c/kg liveweight for Fullblood feeder steers last week.

Poorly-bred F1s suffer alarming declines

While current prices for well-bred F1 feeders still represent a very healthy premium over the broader Australian feeder cattle market, it is at the lower-end of the F1 feeder scene where the real damage is now being seen.

Dramatic price falls are now evident for feeders of less desirable genetic merit.

Wagyu seedstock (Fullblood) breeders have been hard-pressed to keep up with demand for young, paddock raised herd bulls in the past two years, often at highly attractive prices.

Some of those young bulls, Beef Central has been told, went into all manner of commercial cow herds other than Angus – some with considerable Bos Indicus or Euro content.

“The buyers in many cases did not have a good understanding of the genetic requirements to deliver consistently high marbling performance in F1 programs, and were prepared to ‘put a Wagyu bull over virtually anything,” one supply chain manager said.

What’s clearly evident in the market now is that F1 Wagyu feeders fitting that description are being severely punished in the marketplace.

“Those F1s are becoming ‘commodity’ cattle very quickly,” a large Queensland supply chain manager said.

“They are now turning into the equivalent of a crossbred (flatback feeder) that would go into a 70 or 100-day program – worth 300c/kg, and as low as 290c/kg or those out of Indicus-type dams,” he said.

“There’s been a shock factor when prospective suppliers with those type of cattle ring up for a price, and find that instead of having a ‘5’ at the front, they are being quoted around 300c. It’s a huge reality check for some people, because they still expected that those cattle, just because they were by a Wagyu bull, would go into a longfed F1 program, when the reality is that they will not,” the contact said.

“Producers in that position have understandably not been taking the news well, but the reality is that over time, the market will determine what those cattle are worth.”

The contact said his business was getting ‘a lot’ of offers for those ‘non-descript’ F1 feeder cattle over the past couple of months, typically out of Hereford or crossbred dams in the south, and crossbred dams in the north. That would coincide with matings happening in 2016.

“Some of these people have been sucked-in by entrepreneurial types who had no other agenda than trying to sell expensive young Wagyu bulls, fuelled by earlier eye-catching F1 prices,” one supply chain contact said.

How long will current supply/demand conditions last?

All stakeholders who contributed comment for this article were of the view that there will be at least two years of pressured prices for F1s – especially for those animals of lesser quality.

“A lot of those calves born last year or early this year will take a long time to work through the system,” a contact said. “I don’t think we’ve seen the bulk of them yet, by a long way,” he said. “There’s at least another wave (calf cycle) to come.”

“This problem is only going to get worse, because there are more of these cattle yet to come to market over the next year – not less,” another contact said. “The number affected will be in the high tens of thousands, in my opinion.”

What’s the future market end-point?

Questions are now being asked about how this product is presented to the market.

While established Wagyu beef supply chains have their reputations to uphold, there would be nothing to stop unscrupulous operators making ‘Wagyu’ claims on carton lids or labels on F1 product fed for 100-days or less, that carries only very moderate marbling.

“The reality is, a breeder can put a Wagyu bull over a Belgian Blue, and still legally describe and sell the meat as Wagyu F1. The risk now is that unscrupulous operators (not established brand programs, whose reputations are at stake) could now push some very low quality ‘Wagyu’ meat onto the market, exploiting this current over-supply of poorly bred F1s,” one of the contributors to this article said.

“If they end up in the domestic market, fed for 70 or 100 days and labelled as Wagyu product, it could be a disaster, giving the Australian consumer the wrong idea about what Wagyu beef is all about.”

Poor financial performers

A spokesman for a large Queensland Wagyu supply chain said kill results consistently showed that the worst financial performers were F1 cattle of unknown quality bought ‘opportunistically’ on the spot market, rather than through supply alliances where cooperating breeders better understood requirements.

“It’s high risk, after 400 days on feed, and there’s no return in it,” he said.

The contact said he was receiving ‘a number of calls’ each week from producers who had started breeding Wagyu F1s in the past year or two, who were now, increasingly desperately, looking for homes for the calves.

“For many people who just went out into the market and bought a line of Wagyu bulls, without doing a lot of research, this is their first calf drop since the big price rally started in late 2015,” he said.

“Those people supplying well-bred, consistently performing F1s who are aligned with a branded program supply chain will survive this supply period just fine. For others, it will be a lot more difficult,” he said.

Several sources said the reality was that there were large numbers of these ‘questionable’ F1s that were now worth “not much more than a conventional shortfed trade animal.”

Several suggested a liveweight price for that type of animal of 300-350c/kg in the current market.

“There is certainly a huge contrast in value in F1s at present, based on genetic quality, anywhere from 300c to +500c/kg,” one source said.

“For those who are in the bottom end of that range, unfortunately they are going to have to take that price, or until such time as they can prove the performance of their cattle, and their breeding decisions.”

Asked to describe the differences between the more desirable F1s and others in the current market, one manager said the better feeders were out of good quality Angus dams, mated to Fullblood Wagyu bull lines of known F1 progeny performance. The remainder were out of a wide spectrum of dams, many including Euro or Bos Indicus influence, and often sired by ‘indiscriminate’ Wagyu bulls from unrecognised or obscure sire lines.

“There’s a sea of those random crossbred calves out there,” he said. “Certainly there were some producers who in the past couple of years used Wagyu bulls over Brangus, Hereford, Santa or Ultrablack type cows, who were looking for a bit of calving ease on heifers or whatever. Those guys would be happy to get 300-330c/kg liveweight and think that’s not too bad. But there are many, many more who saw the huge figures being paid two years ago when supply was genuinely short for F1 Wagyu calves and dived-in, thinking it was easy money.”

“But we’ve reached a time when those purchase outcomes have been realised, and the market is now responding in terms of performance expectations on those cattle.”

Adding to the dilemma is higher ration price, caused by elevated grain prices. Lotfeeders stressed that they could not afford to long-feed poorly bred F1s that are not going to perform, marbling wise.

“At today’s ration price, producing even a marbling score 3 F1 after 300 days, I could not afford to pay more than around 300-350c/kg liveweight for those cattle. And they are worth less than that if they are actually damaging the Wagyu ‘brand’ reputation,” one source said.

What is the future for ‘unloved’ F1s?

Supply chain managers said the large population of less desirable F1s now emerging were most likely to enter shortfed programs, either 70 or 100 days, where marbling was not a high consideration.

“Some of those feeders may produce some desirable meat quality, in terms of an extra marbling score, but also they are likely to demonstrate inferior growth rate. You’ve got a growth compromise in crossing to Wagyu, but potentially, a small meat quality increase in shortfed programs.”

“Some MSA yearling-type brand offerings might be happy that they extract a little bit more marbling. Some could even consider a short-term MSA Wagyu shortfed branded program – it’s just too early to tell.

“But making that difficult is that the US grainfed industry is currently churning-out USDA Choice and Prime (marbling score 3-4) beef in abundance, and at very competitive prices. Pulling a marbling score of 2 or 3 out of those slow-growing F1 cattle would be a challenge.”

All stakeholders spoken to for this report stressed that there was still an attractive premium for Wagyu F1s bred from the right, predictable cow herds, using the right sire line genetics, and linked under supply relationships to brand programs.

“But for the others, it is going to be difficult. There is no such thing as easy money when breeding cattle, and there never has been. It’s just going to take some time for some people to learn that lesson.”

“Certain people did the Wagyu industry no favours by spruiking the big numbers being paid for F1s two years ago. It created a goldrush mentality, but it was never sustainable, because short-term supply/demand was out of kilter at the time.”

“They were never accurate, reliable, or sustainable price levels, and some people were misinformed. Those people who have not educated themselves well-enough to make an appropriate breeding decision are now starting to pay the price. A heap of people who thought a venture into Wagyu F1s was going to be easy money are now starting to learn otherwise.”

One large player said he did not anticipate that the overall level of Wagyu F1 breeding in Australia would diminish greatly as a result of what was now unfolding.

“What will change, through economic lessons, is a response to the need to breed the right cattle, that Wagyu lotfeeders know will be more likely to perform. The gold-rush era is over,” he said.

Feedlot capacity limitation?

Several lotfeeders rejected recent claims made by the Wagyu seedstock sector in metropolitan media that the main limitation on the Wagyu industry at present was feedlot capacity.

“Feedlots are a long way from working at capacity,” one operator said. “Current occupancy is around 80pc. But if there is a value proposition in feeding Wagyu – and I believe there is, for the right animal – then the capacity issue will look after itself. If there is greater value and margin in feeding Wagyu over conventional cattle, lotfeeders will simply displace those other cattle. So space for Wagyu is in fact virtually unlimited, and it is wrong to suggest otherwise,” he said.

“If the people who made those comments had a better grasp of their own industry, they would realise that the ‘limitation’ is not feeding capacity, but the poor breeding decisions that have been taking place. Thinking a breeder can put a Wagyu bull over just anything for a huge reward is the biggest limiting factor to industry growth.”

“Whilever Fullblood Wagyu producers are selling 80 or 90 percent of their male calf drop as bulls, that was not helping the industry progress, one bit.”

Reflecting the ‘dramatic’ turnaround in demand for bulls this year, several feedlot managers told Beef Central they had been offered lines (not accepted) of Wagyu F1 steers that had started life intended as breeding bulls, only to be castrated at 12 months of age to become feeders – suggesting their owners had given-up trying to find homes for them as herd bulls.

One pointed to recent Wagyu bull sales on AuctionsPlus, where few transactions had been completed, and most of the sale entries carried BreedPlan EBVs at, or below breed average.

“There’s still an enormous oversupply of crap, based on entrepreneurs still trying to cash in on the big money that was around two years ago. The industry has a very big evolution ahead of it to get back to a rational space,” he said.

“There’s evidently still a lot of operators within the Wagyu industry who don’t get the industry, where the Wagyu value sits, and the long-term future.”