Bakso ball soup is the Indonesian equivalent of the Australian meat pie or the American hamburger, fast food that is cheap, delicious, available everywhere, a national icon, loved by all.

And like its foreign counterparts, the immense popularity of the bakso ball means that the business of its manufacture and retailing makes it a major part of the national food economy.

The introduction of Indian beef to the bakso ball industry is largely responsible for an estimated 50 percent reduction in demand for fresh beef sourced from imported cattle within a space of less than 12 months.

West Java has been the principal location for Indian buffalo distribution and is the same area primarily supplied by imported Australian cattle.

The commercial attraction of handsome trading margins for Indian product has meant that it has found its way much further afield where it has also created similar disruption for locally bred slaughter cattle. Official statistics are not available to prove my 50 percent claim but I do have verbal confirmation from a wide range of feedlot operators, cattle traders and abattoir sources that demand for their slaughter cattle crashed by around 50 percent very soon after the introduction of Indian beef and has stayed there ever since.

It is also well known that Indian beef has not been well accepted by wet market retailers supplying beef to households so the manufacturing of bakso balls is the obvious destination for these massive volumes of Indian product resulting in a ball park potential financial loss to the slaughter cattle industry of up to 300,000 head of live cattle or about AUD$400 million per year.

So it is important to understand how the combination of this unpretentious product and Indian buffalo beef has wreaked such havoc on Indonesian cattle producers, Australian live exports and the Indonesian feedlot industry.

My friend, David Heath, introduced me to the owner of his favourite bakso shop, “Bakso Yanto” near Tabanan in Bali. Pak Yanto agreed to allow us to follow his bakso making process so that we could better understand how this local food is produced and subsequently exerts such a massive impact on the national economy.

Bakso is a small, rubbery ball, about the size of a large grape, which can be made from beef, chicken or seafood along with many other ingredients which are then presented in a hot soup with noodles, vegetables and traditional spices. Very simple, very delicious and very cheap. A steaming bowl of Pak Yanto’s wonderful bakso soup, including 8 meatballs sells for Rp10,000 or less than one Aussie dollar.

After buying 15 kg of hind quarter beef (Bali cattle) from a Halal wet market butcher in Tabanan at about 4 am, we then travelled to a specialist bakso mixing place (also Halal) where three large diesel powered machines were busy grinding their customers ingredients into a thick, sticky paste.

The beef is combined with 3kg of tapioca flour, 500 grams of fresh garlic, a large number of herbs and spices (his own special mix) ice and water. These additional ingredients are purchased from a small shop next to the grinding machines.

During the mixing process, water and ice are added to expand the volume of the paste as well as keep the temperature of the process down to ensure the meat is not cooked in the grinding process.

This belt driven, stainless steel dish grinder spins at high speed to allow the ingredients to be gradually folded into the mix along with cold water and ice to produce a finely ground, sticky paste ready for cooking.

The bakso mix arrives back at the shop in time for Pak Yanto to have breakfast and then start making his meatballs at about 7am.

One small family run shop is using 15kg of fresh beef to make and sell 20 kg of bakso balls every day of the year except for religious holidays.

There are hundreds of thousands of bakso makers and sellers like Pak Yanto all over Indonesia as well as large manufacturing companies that make bakso in industrial quantities for supermarket chains and institutional buyers.

The critical issue in the bakso/Indian buffalo nexus is that the meat is ground into a paste so that the original meat product is visually unrecognizable.

There are those traditionalists, like our friend Pak Yanto, who insist they will never use anything except the traditional cuts of fresh cattle beef as they believe that the product made using frozen Indian buffalo has an inferior flavour and is therefore unsuitable to serve to his loyal customers.

Other manufacturers, including some of the larger industrial companies are however quite comfortable using Indian buffalo while making some modifications to the recipe to maintain a taste that is similar to the original beef versions.

There is a big difference between Pak Yanto’s repeat customers who specifically return for his tasty soup with its well deserved reputation and the millions of truck drivers, workers, school children and travelers, simply looking for a quick, cheap and tasty meal at a road side stall or corner shop during their busy day.

Frozen Indian buffalo wholesales for about 30pc less than fresh beef. The result is the substitution of tens of thousands of tons of fresh beef with frozen Indian buffalo leading to a dramatic collapse in the demand for slaughter cattle with the greatest reduction in the West Java region where Indian buffalo is most readily available.

Unfortunately for the consumer, the retail price of the bakso produced using Indian buffalo is the same as it was when fresh beef was the primary ingredient with manufacturers and retailers retaining all of the windfall margins from the cheaper buffalo input.

The balls are formed by squeezing the meaty paste up between the thumb and forefinger then cutting it off with a tea spoon and dropping it into hot water where it sinks to the bottom. After about 20 minutes in the hot water the balls float to the surface once they are cooked and are removed to dry on rattan trays (top of photo).

Click to watch a short video showing of Pak Yanto’s bakso ball making process.

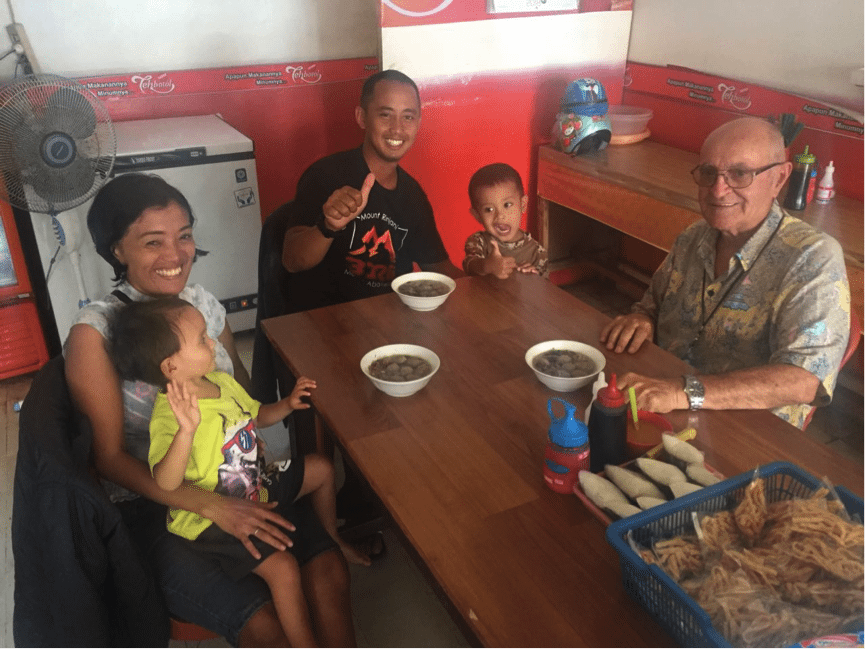

from left – Novi Heath, Edward Heath, Yanto (son of Pak Yanto the Bakso maker), grandson of Pak Yanto and David Heath enjoying a bowl of bakso soup for breakfast.

Former US President Obama lived in Indonesia as a small boy and still regards bakso soup as one of his most favourite meals.

With everyone from small children to Grannies enthusiastic about their frequent meals of bakso soup, imagine the astronomical volumes of beef and other ingredients that must be constantly produced to make these dishes every day for 250 million Indonesian consumers.

While the impact of Indian beef on demand for fresh beef has been great, there are still a large proportion of producers and consumers of bakso that will never move away from locally slaughtered fresh beef.

This should give cattle producers, exporters and importers some confidence that the Indian product has reached its peak levels of disruption with potential for a slow but steady recovery as incomes rise and demand for high quality, fresh beef bakso is rebuilt.

At only 2 and ½ years old, Edward Heath is already a big fan of bakso soup with visits to Pak Yanto’s shop for a bakso breakfast at least 2-3 times per week. It is Edward and more than 200 million other bakso lovers that give this simple product its incredible commercial power.

HAVE YOUR SAY