The importance of fertility rates on herd production and profitability was highlighted in the Australian Beef Report 2020 Vision. The report suggests that a 5pc increase in herd fertility equates to a 7pc increase in farm income.

HERD improvement is a fairly generic term used by many when discussing their reasons behind new sire purchases.

As a term, its loosely applied to cover all aspects of change across the herd, from increasing sale weights through to introduction of new traits. However the risk of using a generic term is to increase the chances of overlooking some fundamentals that are part of an efficient and profitable breeding program.

Introducing new genetics can generally be assumed to be a positive move for a breeding herd. However, the introduction of new genetics doesn’t always translate into increased production or profit.

Without clearly identifying where a herd is positioned, and its progress towards a breeding objective, it is much harder to measure the impact new genetics have had on a program. As a consequence, its often very hard to justify the investment in those genetics, if the returns can’t be easily seen or measured.

Doing the simple things right

One of the characteristics observed among successful cattle producers – those identified as in the top 25 percent of industry for production & profit – is focusing on the things that can be controlled within their systems. The other characteristic is their unrelenting focus on getting the simple things right. When the simple things are done right, the rest of the program has a solid base to build on and to expand.

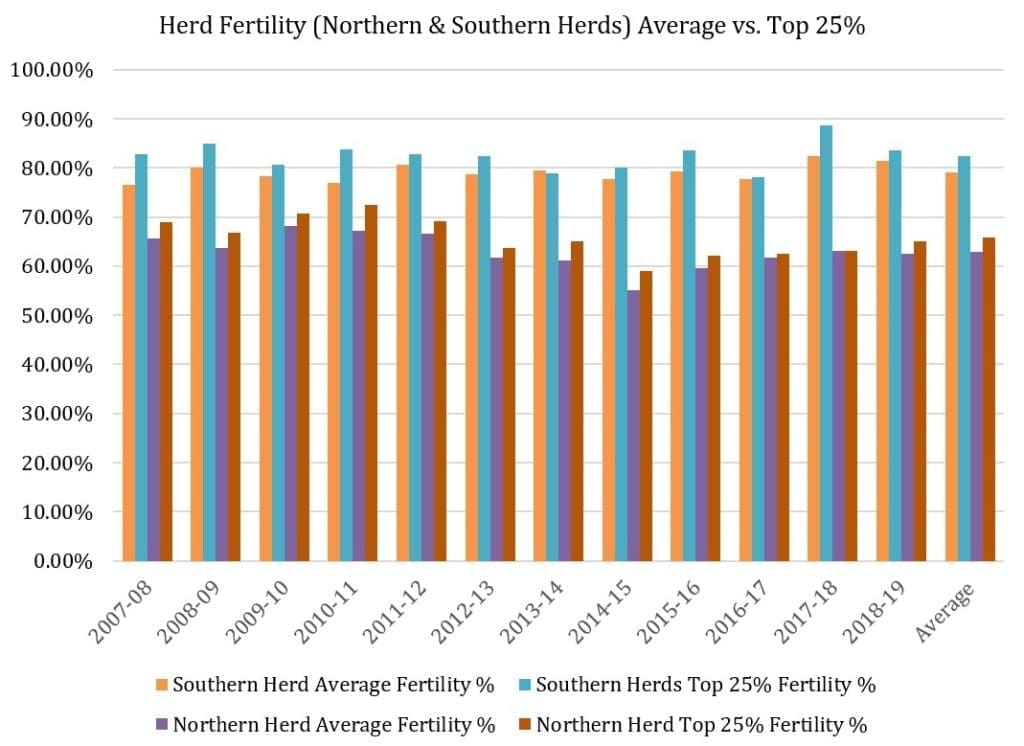

There are many commonalities shared across Australian breeding herds. The largest is herd fertility.

The importance of fertility rates on herd production and profitability was highlighted in the Australian Beef Report 2020 Vision. The report suggests that a 5pc increase in herd fertility equates to a 7pc increase in farm income.

That increase is 3pc greater than the boost to farm income achieved through lifting sale weights by 5pc. In many cases fertility is also a much easier area for producers to address in order to make some significant positive changes.

Taking the time to consider the data contained in the Australian Beef Report 2020 Vision, there are some valuable messages on offer. In the case of herd fertility, it’s very apparent that there is a huge opportunity to lift fertility rates in both northern and southern Australian herds.

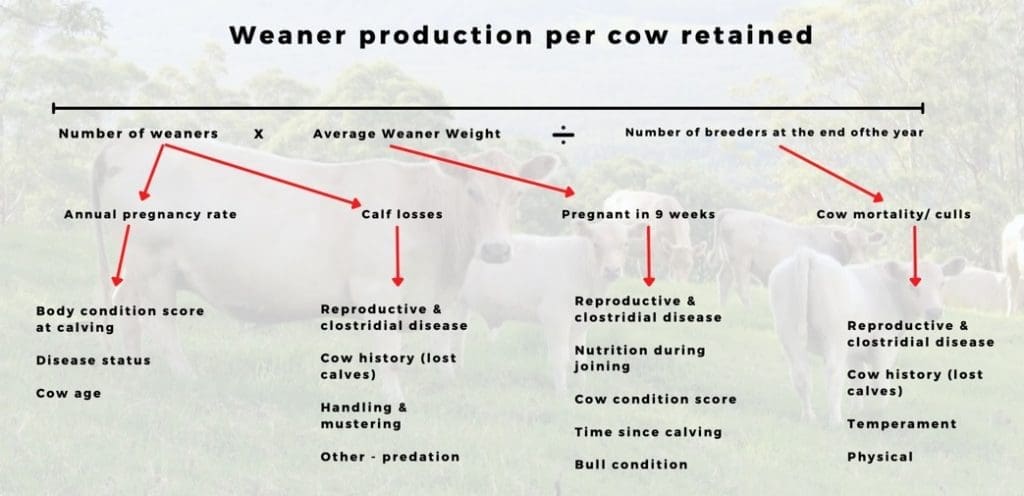

As a trait, fertility has lower heritability than other traits. In practice this means producers need to have more focus on managing the environmental effects on their animals in order to maximise their fertility rates.

The environmental effects fall back to the management of factors such as feed availability – particularly energy intake; body condition score at calving; and on the goals that have been set around heifer selection and growth to their first joining.

Coming back to the point that the top 25pc of producers focus on the things they can control in their business, as well as ensuring the simple things are done correctly, both of these traits require a thorough understanding of the breeding herd.

Collecting data is the first step in identifying where the sticking points are. Of equal importance it provides a place to focus on and to ensure the simple things are being done right.

The FutureBeef team developed a simple checklist of data that any breeder could use in order to check off the key areas in their breeding system.

Source Future Beef (Adapted RaynerAg)

This checklist has around 25 basic indicators for producers to check and assess in their programs.

There are more that may apply to specific locations, however, if these points were assessed in more breeding herds, the flow effect for fertility rates would be significant.

More importantly, these are the simple things to get right and rest entirely within the span of control for producers.

As a point of focus, the lift in fertility will provide direct and fairly rapid improvement to farm income. In the longer term, the investment that producers may want to make in genetics can be directed towards traits that will not only address production goals, but also assist in making the simple things a bit easier to control.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au