PRODUCERS commonly raise a few questions when viewing a bull sale catalogue, particularly on the subject of Breed Indexes and what the value ranges they contain relate to.

These questions often form an underlying need to understand what an Index is describing, and how it may assist in refining a series of choices around certain sires within a catalogue.

Perhaps the simplest way to come to grips with the role of breed indexes is to step back and consider the genetic information that is currently on offer in most catalogues.

Breeding values that reflect the genetic merit of an individual sire are a result of direct measurements of that animal, measurements of relatives and progeny – and increasingly, genomic information. This data is used to calculate EBVs published within Breedplan.

Depending on the breed, the number of individual EBVs can vary significantly, from a half dozen in one breed through to 24 in the Angus breed.

One of the challenges that consistently confronts producers is how to apply this genetic information to select a group of sires that will suit their breeding objectives, environment and market. In simple terms, how much weighting should be attributed to traits around growth; fertility or eating quality.

Seeking balance

The development of breed indexes is a result of these challenges. The intent of an index is to offer producers the opportunity to make more ‘balanced’ decisions on the genetic suitability of a sire to a specific production system and market.

As many producers know, the risk with using EBVs can be an inadvertent preference towards specific traits e.g. growth. This inadvertent preference can lead to unbalanced selection decisions where the bulls a producer considers are high-growth animals, but may lack the other genetic traits required for their environment and market.

In my experience, it’s often the result on unbalanced selection that causes producers to be critical of EBVs or to be disappointed in the direction their animals have moved. While this disappointment is perhaps understandable, the issue lies in the decisions made with the EBVs, not the actual EBVs themselves.

In order to bring some balance into the selection process, a program known as BreedObject is used to place weighting on the production requirements for a beef business targeting specific market end points.

These breeding scenarios are created by individual breed societies based on their membership base and breed focus. As such, producers need to recognise that indexes can’t be compared between breeds and are only for use when sorting through bulls from the same breed.

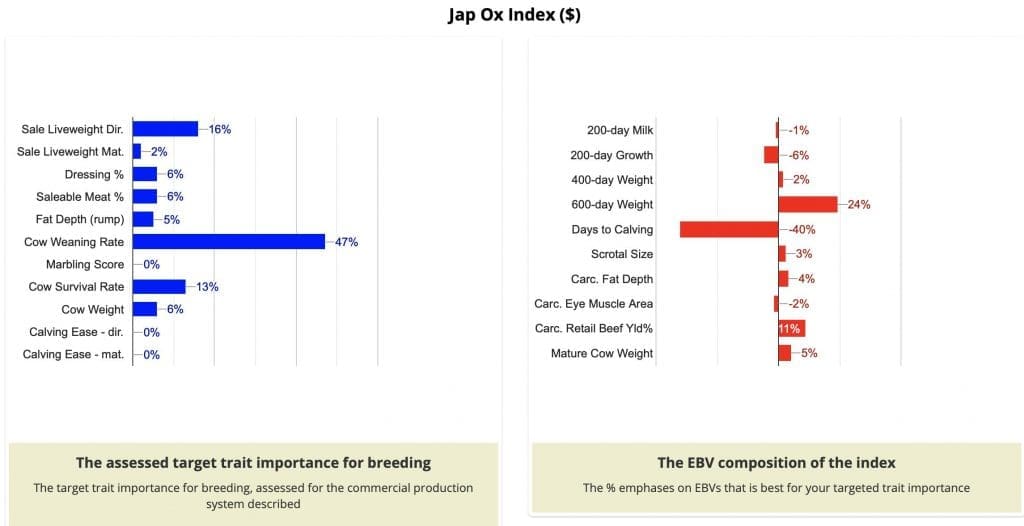

The table above highlights the development of the Brahman Jap Ox Index within BreedObject. On the left-hand side are the traits of importance within the breeding system. The key profit driver within this system is cow weaning rate followed by the sale weight of progeny. When these traits and their interaction with each other are considered, it’s possible to place a weighting on each EBV (highlighted in the red columns). So, there is a focus on reducing days to calving and increasing 600-day weights in this index.

The index is then published as a single figure. In effect the index is an EBV describing profitability for the chosen commercial production scenario and market. The index published as a dollar value refers to “net profit per cow mated” to reflect the value the sire’s genetics will offer across the supply chain.

As noted in recent genetics columns, breeding is a long-term process. The risk with unbalanced decisions (even if it was not intentional) is a change in the traits and performance in a herd that requires significant efforts to correct and overcome.

The research across Australia in programs such as the CRC for Beef Genetics, and the Northern Repro-nomics project demonstrate how well EBVs work within breeding herds.

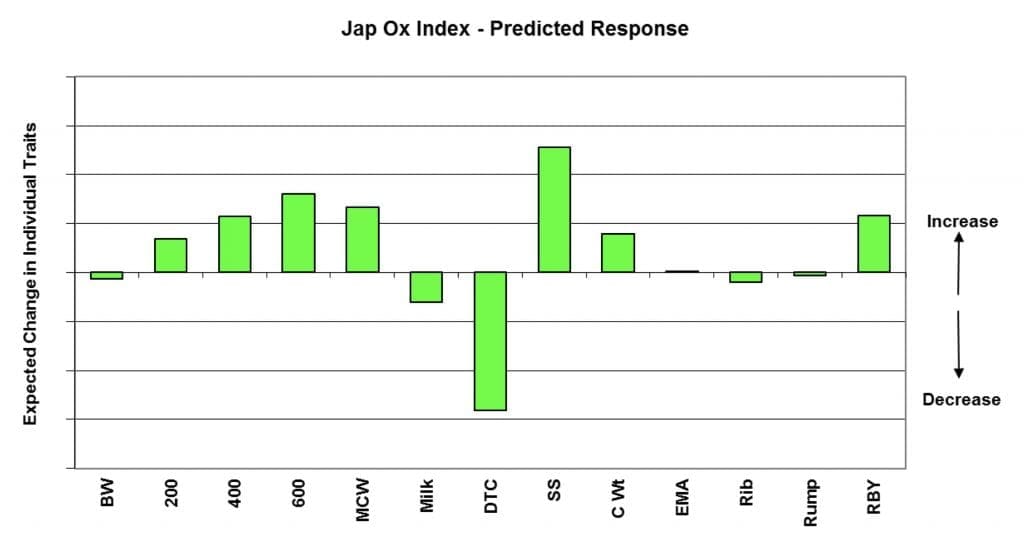

Continuing with the example of the Brahman Jap Ox index, producers who select bulls that are above the breed average for this index would see their herd start to reflect these traits. In particular the reduction of Days to Calving, an increase in 600-day weights and increases in carcase weight and retail beef yield.

Here’s some final key points that need to be emphasised when using Indexes.

The index is valuable for selecting the first draft of bulls to consider for their overall (balanced) suitability for a program. Within this draft, bulls should be ranked on the traits that are of importance to an individual operation. So, it is possible to still select for a trait within the parameter of the index and avoid skewing a herd too far in one direction.

Finally, this process identified the genetic potential of an animal. In practice it creates a sale list that should form the basis of a physical assessment.

This assessment, along with additional information such as the results of a Bull Breeding Soundness Exam, become the key components of informed selection for any breeding program.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. He regularly attends bull sales to support client purchases and undertakes pre-sale selections and classifications. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. He regularly attends bull sales to support client purchases and undertakes pre-sale selections and classifications. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au