The impact of buffalo fly was reported to cost the industry around $99 million each year in lost productivity and treatment cost

THE economic impact of Buffalo Fly on the Australian beef industry cannot be underestimated.

Meat & Livestock Australia has ranked buffalo fly as the third most significant disease/parasite challenging the Australian beef industry. The first is cattle tick, and the second, pestivirus.

At a recent farm visit I attended on the North Coast of NSW, buffalo fly was the principal topic of concern. The fly season appears to be extending further into the year, and buffalo fly populations are moving further west into the NSW Northern Tablelands and even as far as the North West Slopes.

The cost for some producers is astounding. Trial work in the wet topics identified production losses of up to 16 percent, while for many producers further south, control costs including additional handling and treatment have a definite increase in costs and animal loss.

Although there are proven control methods, its worth considering the role that genetic resistance can play in reducing the impact buffalo fly can have within a beef herd.

While bos Indicus cattle are genetically more tolerant of parasites, there is a wide range of tolerance within most herds.

This has been recognised in the advice provided by MLA on buffalo fly control, which highlights that there are often a small group of animals that are more irritated and allergic within a group. This often results in early treatment for the entire herd, which may not be required.

While removal of those individuals eliminates the problem of individual animals with low tolerance, it doesn’t account for the underlying herd genetics. There are potentially other animals such as siblings or progeny that are also less tolerant.

Selection for resistance

Visual selection also doesn’t really account for the other traits that the animal may have that are of economic importance within the herd. It is often difficult making decisions crush-side about an animal’s lifetime value.

Parasite resistance is a measurable genetic trait. While it is not yet included in published EBVs in Australian beef breeds, there is a determined effort to collect data on animals and start to use that as the formation of an EBV for resistance.

Parasite resistance is a measurable genetic trait. While it is not yet included in published EBVs in Australian beef breeds, there is a determined effort to collect data on animals and start to use that as the formation of an EBV for resistance.

In discussions with Paul Williams from Tropical Beef Technology Services (TBTS), data collection is growing through the efforts of research herds and several seedstock producers.

Mr Williams explained the process of the move to develop Tropical Adaption Traits during a recent genetics workshop in Armidale.

“These are traits that have an economic value for production and for cost reduction and so are important areas to focus on,” he said.

The data that needs to be collected in order to develop a trial EBV is reasonably straightforward. Producers should record lesions caused by the parasite in late summer and through to early autumn. So now is a good opportunity for producers to consider undertaking these assessments.

The scores can be taken on animals of any age. It’s important to remember that older animals are likely to have more fly scars.

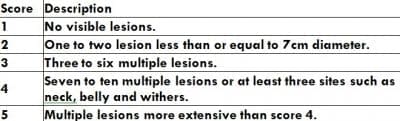

Scores should be collected following the Breedplan template that ranks scars from one to five, as follows:

For any breeders thinking about helping contribute to the development of this EBV, it is important to remember some basic considerations.

Firstly not all animals in a group should have the same score. There will be some differences, and if the scores don’t reflect this, the data wont be much use in developing the EBV.

If you are applying a control for fly, then this needs to be reflected by assigning them to a management group. It’s essential that the differences in scores should be as a result of their genetics, and not the variation in control methods. And lastly its generally better that one person does the scoring of all animals that are being assessed on a particular day. This keeps the scores more consistent.

The scores can be submitted to the normal Breedplan centre. Breeders who are unsure about the process to follow can contact their breed office or the TBTS team.

Developing an EBV for this trait is a positive step. The opportunity to select for resistance can lead to reduction in treatment costs and production losses.

However at a deeper level, including this genetic information increases the selection opportunities for producers across northern Australia and northern NSW.

Longer term, there will be the opportunity to select animals that have proven production traits for growth and fertility and are also more genetically resistant to buffalo fly.

While the EBV is still a work in progress, this EBV along with a similar EBV for tick resistance do have the potential to significantly reduce the cost of control, moderate chemical use and reduce production losses for the northern industry.

Alastair Rayner

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. He regularly attends bull sales to support client purchases and undertakes pre-sale selections and classifications. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au