“When the Paris Exhibition [of 1878] closes, electric light will close with it, and no more will be heard of it.” – Oxford professor Erasmus Wilson (pictured) 1878.

“When the Paris Exhibition [of 1878] closes, electric light will close with it, and no more will be heard of it.” – Oxford professor Erasmus Wilson (pictured) 1878.

CHANGE can often be a confronting issue for people.

Change, particularly if the idea, development or technology challenges well established routines or patterns of behavior is often denigrated, overlooked, and disregarded.

While there are plenty of innovations that have been heralded as being capable of lifting industries to new levels of performance, only to fail, many more have gone on to shape and improve the way an industry operates or influences the way in which the customers of those industries behave.

Well-constructed, peer-reviewed science can offer not only developments for industries, but can lead the way to other innovations that can markedly improve the well-being of individual and businesses.

The benefit of peer-reviewed science is that the process of research, the results and the findings are open to challenge and have to be much more solid than a collection of experiences of one person at one time.

However the resistance to change can often see people placing greater weight and value on the experiences or opinions of one person commenting on social media, than on the solid body of research conducted for that particular issue.

Reader comments

Nowhere is this truer than in the approach some people have to performance recording and programs such as BreedPlan. Over the course of writing these columns for Beef Central, I’m often in receipt of angry emails and comments from producers who choose not to use BreedPlan, IGS or even consider the newly available Genomic Breeding Values.

A recent comment received by email: “Breedplan is a complete waste of time, my calves never look like they are supposed to, and my breed is losing its way,” is not an unusual sentiment.

Over such a vast industry as the Australian beef industry, differing schools of thought are always likely. The best ideas and research have often come from differing ideas. However, opposing science or a technology for ideological reasons may result in missing opportunities to make an enterprise and an industry more successful, and in the long term more profitable and sustainable.

In the last few weeks I have been contacted by Brahman breeders, several of whom wanted to point out the increase in birth weight within their breed – in particular, actual birthweight of heifers’ calves. They laid the blame squarely on performance recording in these comments.

In the last few weeks I have been contacted by Brahman breeders, several of whom wanted to point out the increase in birth weight within their breed – in particular, actual birthweight of heifers’ calves. They laid the blame squarely on performance recording in these comments.

While it can be tempting to find a single point of blame, the reality is never that clear. Many people choose to overlook the simple fact that the phenotype of an animal (its physical appearance) is a direct outcome of genetics and environment. How well this is understood, and the interactions managed are essential if to achieve desired outcomes.

It is also important to bear in mind that 87 percent of the current cow herd (including heifers) are influenced by the last three generations of sires. While a bull directly contributes 50pc of his progeny’s genetics, the ongoing influence of past sires in the dam’s contribution shouldn’t be forgotten.

Making genetic change is a time consuming process, and without some information on the presence of particular traits, how well can producers select to improve in specific areas, or equally to look and to avoid specific traits that are unfavorable to their environment and enterprise.

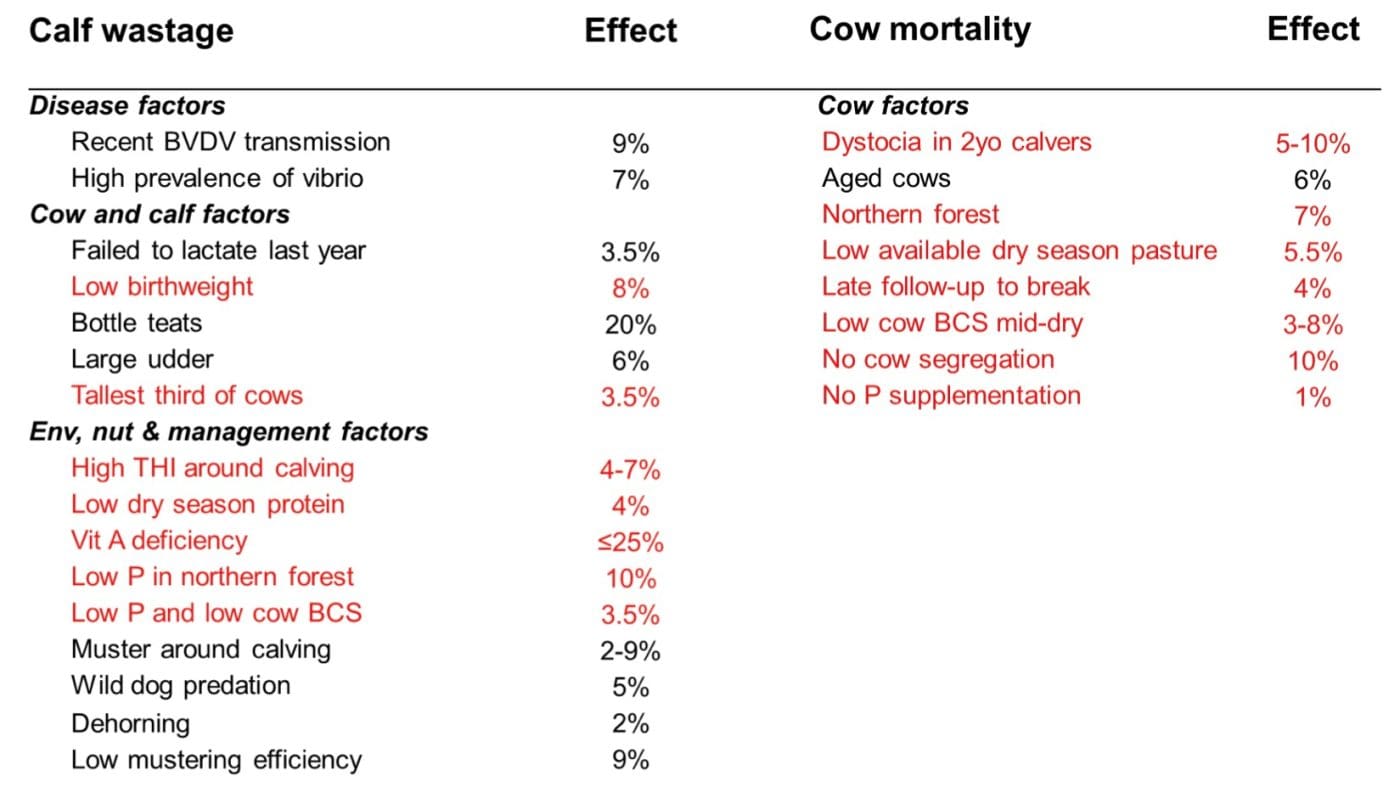

The Calf Alive project has delivered many useful, proven lessons for producers in northern Australia. It’s worth noting that calf wastage averages around 10pc across the region. The opportunity to reduce these losses can result in dramatic production and profitability outcomes for the industry.

Source: Calf Alive 2021 – Future Beef

The major source of losses in calves in northern Australia is fairly extensive. Across that list of factors are a number that can be resolved through changes to management, either timing of events, husbandry decisions or health protocols.

There are also several areas where genetics are likely to make a difference – if the right bulls are selected.

Attempting to resolve an issue such as birth weight, either because the calves are too small and struggle to survive the early days after birth, or too large, creating losses from dystocia is much harder if there is no clear knowledge of the genetic contribution from the sire or from the dam and its grandsires. Making assumptions means the problem is never effectively addressed or improved.

One of the challenges of performance records is to have enough data, so that the true shape of the population can be measured, and the leading animals identified.

In the process of doing that, the rankings of some animals will change as their relevance to the population becomes clearer. Just because an animal moves up or down the ranking isn’t a reason to stop doing it, because the results of the evaluation weren’t what was expected.

There is more value knowing where an animal really sits within a breed.

In doing that, there is plenty of opportunity to allow clients and producers to look at animals and decide if they should be using or not using that sire in their programs.

The decision not to use a sire is equally as valuable in some cases as using him.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld, and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld, and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au