ONE of the most common expressions used in discussions regarding crossbreeding is that it represents “the only free lunch” for cattlemen and women.

It is difficult to know who to attribute that famous expression to, but it certainly has become widely used across the industry, both domestically and internationally.

Another equally recognisable quote came from the famous economist Milton Friedman, who in 1969 said, “There is no such thing as a free lunch”.

Of the two expressions, I tend to think there is more truth in the second.

While there is always a desire to get something for free, in cattle production, there is always a cost associated. It’s important in designing breeding systems, to allow for that cost and manage accordingly.

Crossbreeding does offer producers some significant advantages for their production systems. There is an opportunity to select and join breeds to capture specific traits to complement each other.

This probably should be seen as the first real advantage of crossbreeding. The second is the opportunity to take advantage of non-additive breed effects, and so use the value of hybrid vigour (heterosis) to achieve breeding goals more efficiently.

At a conceptual level, these two advantages are extremely appealing.

However the application of crossbreeding is often less rewarding for many producers in practice.

Heritability

It’s very easy to be excited by the thought that the “free lunch” from hybrid vigour will result in significant changes across all the traits a producer is seeking to improve. When this doesn’t eventuate, many producers become frustrated or disillusioned with the process of crossbreeding.

It’s important to firstly recognise that the degree to which heterosis that is realised for a particular trait is inversely related to the heritability of that trait. In practice, this sees traits of low heritability, such as those associated with reproduction and fertility generally benefit from heterosis the most.

While many production traits are improved through heterosis, the actual results often fail to live up to the expectation producers have as they wait to enjoy their “free lunch.”

Perhaps one of the greatest disappointments comes in the choice of animals used within a crossbreeding program. Although hybrid vigour will be an outcome from joining two different breeds, the selection decisions behind that joining are crucial.

Using animals that are breed average or below breed average won’t result in a significant improvement in production. Combining average with average will result in little actual change at the production level.

In any discussion on crossbreeding, the issues surrounding cow size and environmental suitability should be included. One significant outcome of crossbreeding is the increase in mature cow size and a corresponding increase in feed consumed annually. Quite simply, crossbred cows will eat more, and in most cases, producers will be required to run fewer cows to fit within a property’s feed availability across the year.

In most cases this resulting reduction in cow numbers is offset by gains in other areas of production – in effect, becoming a cost-neutral impact on a business.

However this isn’t always true. There are many examples where crossbred herds are operated with poor management structures, unclear selection parameters resulting in less productive animals, or poor marketing choices, which can combine to add to costs, and be far from the “free lunch” many producers were expecting.

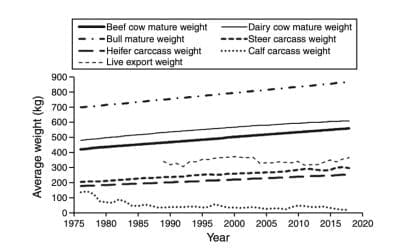

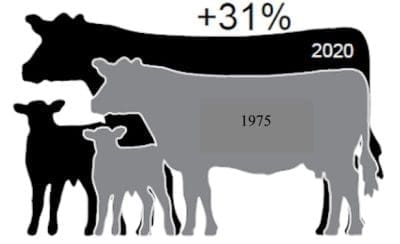

Perhaps the other factor to be considered in the cow size discussion is the fact that Australian cattle have been increasing in size over the past 45 years. In a recent publication by Geoff Fordyce, the increase in cow size, as well as steer and heifer weights are clear.

Based on ABS figures, the average Australian cow is now some 31pc heavier than in 1975, while steer weights have increased at the same time to be almost 50pc heavier..

Australian cows are increasing in size. Cows in 1975 averaged a little over 400kg liveweight, while today, the figure is close to 550kg. The impact this will have on crossbreeding decisions shouldn’t be underestimated.

As the size of the breeds included in the program increases, the mature weight of crossbred females will also be greater. And if this gradual increase in mature size hasn’t been accounted for, producers may find their feed demand is much greater than anticipated (even allowing for the increase through hybrid vigour). The consequences of this can see feed deficits occurring earlier and lasting longer.

Without adequate management plans to offset these issues, it’s difficult for the full expression of hybrid vigour to be realised, and so limit the results of the crossbreeding program.

Without doubt, well designed crossbreeding programs can result in increases in production and profitability. However, focussing on the concept of it being a “free lunch” overlooks just what might be required to get that benefit.

It’s essential to look at both direct costs, such as purchasing sires that are above breed average from another breed, through to opportunity costs, such as running lower cow numbers in any evaluation of crossbreeding.

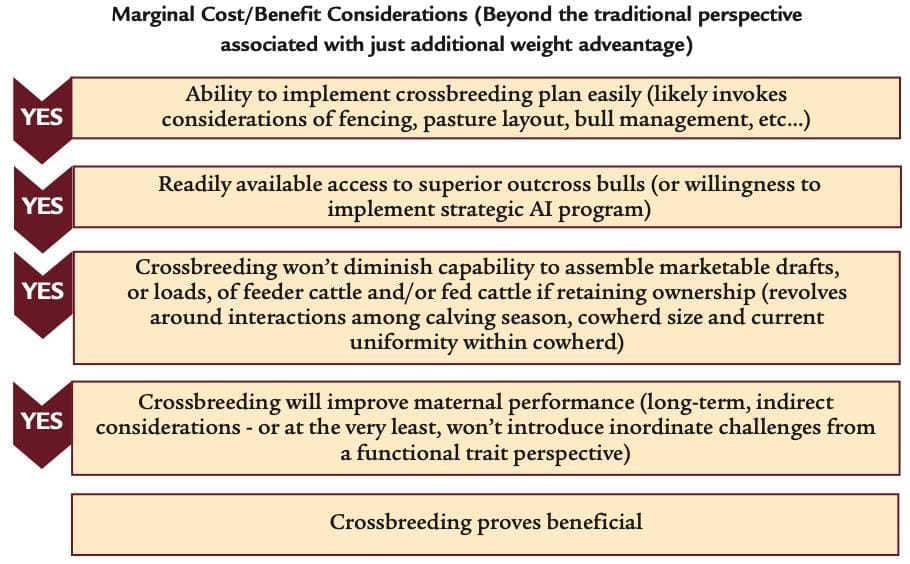

One of the best ways to consider these issues, was presented by Dr Nevil Speer, from Western Kentucky University. He presented a simple decision tree that can help producers thoroughly consider if crossbreeding is an option.

Source: Dr Neil C. Speer – Western Kentucky University “Crossbreeding Considerations & Alternatives in an Evolving Market”

Using a decision tree such as the one above is probably the best starting point for any producer considering implementing a crossbreeding program. Having some rational analysis of the costs, as well as the opportunities ensures a program is bedded into reality and not simply built around hope of a desirable outcome.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted via the reader comment panel below, or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted via the reader comment panel below, or through his website www.raynerag.com.au